As I walked down a path at the UC Santa Cruz arboretum, I heard them.

The buzz was distinct. It wasn’t the thin sound of a common housefly or the high-pitched trill of a mosquito. This vibration had some weight behind it.

I knew it was a bumblebee before I saw it. Years of studying these hefty, fuzzy bees had trained my ears to recognize their buzz.

Their sound is more full-bodied than that of a honeybee. I think of the bumblebee as the opera singer of bees; perhaps its stocky body gives its sound a deeper resonance.

As I watched the clumsy bee move from one pink flower to the next, I wondered if was delusional. Can you actually identify an insect just by sound?

It turns out I wasn’t the first to think about this. In 1952, Albro Gaul published an article in the journal Psyche on “audio mimicry.” Just as a harmless fly might have evolved the same color patterns as a dangerous wasp to avoid attack by predators, Gaul wondered if a fly and a wasp which looked similar, might also sound similar. Could a predator tell their sounds apart or was this last piece to complete the perfect disguise?

Gaul grabbed a microphone and electro-mechanical transducer and set up a recording session.

As insects beat their wings rapidly, the air around them vibrates creating a buzzing noise. “The frequency you hear from flying insects is based upon the length, width, and density of the wings, as well as how fast and in what pattern they flap,” Susan Villarreal, an entomologist working at Cornell University, told me in an email.

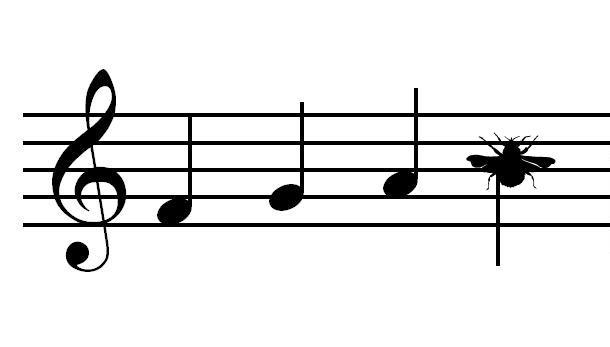

Gaul measured the tones the fly and wasp produced as they beat their tiny wings. The wasp clocked in at about 150 wing-strokes per second and the fly, at roughly 147 wing-strokes per second (give or take 2 strokes in both measurements). This swift flapping created tones that, Gaul argued, are somewhere between D and D# — sounds he couldn’t tell apart.

Gaul admitted that the impressive match in tone might have been a coincidence. After all, he only looked at one wasp and mimic pair.

Over 50 years later, researchers from Carleton University and the University of Cincinnati ran a similar experiment with six different bees and wasps and six flies that mimic them.

The wasp and bee species they collected produce a distinct sound when a hungry bird attacks them.

Whether the noise is meant as a warning to the bird that the insect it has in its beak is dangerous or simply an alarm to startle the foe, is a mystery. But fly mimics also produce sounds when grasped by a predator. But do these buzzes sound the same?

The researchers busted out the audio equipment to find out.

They found that flies mimicking these wasps and bees did not produce identical sounds upon attack. However, for mimicry to work, the impersonator may not need to sound perfect, but simply close enough to avoid death.

Being able to tell insect sounds apart may also be important for insects themselves.

Mosquitos use sound to find their mates. “Males use the frequency of the flying sounds to let them know if the flyer is a female,” wrote Villarreal. And females use the males’ sound to judge the quality of males.

For Aedes aegypti, the mosquito species that spreads Dengue fever, females buzz at 400 hertz and males at 600 hertz. Hikers might want to learn these tones because it’s only female mosquitos that are able to suck your blood.

Back in the arboretum, I might not have been able to name each insect by ear but I did close my eyes to appreciate their music.

#####

Check out the slideshow below for computer-generated sounds of insects in flight: