Last week, to celebrate Earth Day, volunteers around the globe trekked out to forests in Australia, New Zealand, Great Britain, Ireland, Germany, Canada and the U.S. to plant 18-inch tall clones of ancient redwood trees in an effort to forestall global warming by reforesting the Earth with the iconic forest dwellers.

More than a century ago, three redwood trees, each the size of a 40-story building, were felled in the dank emerald forests of Humboldt County in northern California. The stumps of the trees, believed to be 2,000 to 4,000 years old, still emanate from the forest floor. To this day, “basal sprouts” shoot out of the stumps, the largest of which, the famed “Fieldbrook Stump”, measures 32.5 feet across.

Over the years, a small group of dedicated volunteers coordinated by the non-profit Archangel Ancient Tree Archive have collected a handful of those basal sprouts along with branch clippings from the tops of some of the most impressive living redwood specimens on the West Coast. Archangel used those samples to make the world’s first redwood clones, a process that ultimately took four years and $2 million.

Visions of champions

Archangel volunteers climb to the tops of ‘champion’ trees to collect branch tips (image courtesy of David Milarch)

Archangel began as the vision of co-founder, David Milarch, a barrel-chested champion arm wrestler and the owner of a Copemish, Michigan, family nursery. In 1996, Milarch’s kidneys and liver failed during an attempt to quit drinking cold turkey. He had a near-death out-of-body experience in which angels implored him to save Earth’s trees by creating an arboreal Noah’s ark.

Over the next two decades, Milarch, along with his sons Jared and Jake, scoured the U.S. in search of “champion” trees—defined as the largest exemplars of their species that have lived for hundreds or even thousands of years and may be genetically geared for resilience—that they could then clone in their nursery.

The notion that champion trees are endowed with superior genetic traits that make them resistant to disease or environmental or climatic changes is not widely accepted. Some scientists believe the longevity of champions is due more to luck—being in the right place at the right time—than any particular characteristic of the tree.

Milarch admits that nobody knows why some trees live longer than others, but says, “If you find a 3,000-year-old tree, don’t you think we should preserve them to study their genetics for when the science advances?”

Archangel has so far cloned champions of 75 species including the redwood, giant sequoia, Monterey Cypress, and the Monterey Pine. They have also cloned the Methuselah bristlecone pine. Estimated at 4845 years old, this eastern California treasure is thought to be the world’s oldest tree.

Archangel has not limited its cloning efforts to the champion trees of North America. They recently cloned thousand-year-old trees in Ireland—“the biggest, oldest, badass oaks of Ireland,” according to Milarch.

Redwood branch clippings bathe in baby jars filled with nutrients (image courtesy of David Milarch).

Here come the clones

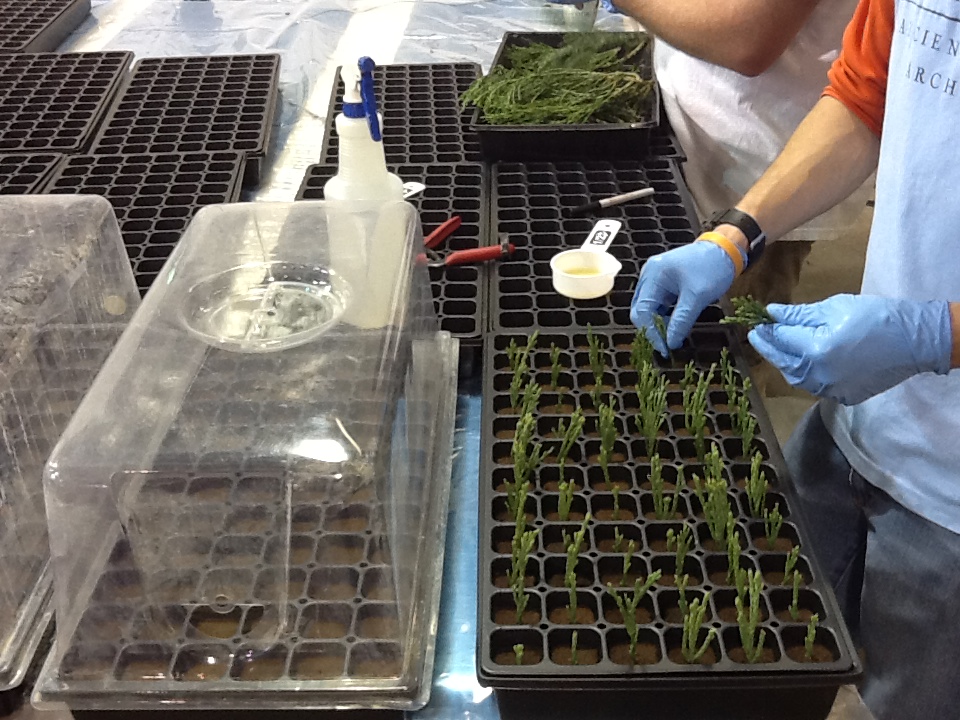

After Archangel’s collectors obtain fresh samples from out in the wild, they pack them up in a cooler and ship them overnight to their Michigan-based propagation lab. Once the samples arrive, technicians gently place the freshly cut trimmings or sprouts into baby food jars filled with a concentrated commercial dip-grow solution. From there, the cuttings are transferred to 2-inch by 2-inch trays filled with a dark brown slurry of hormones, fertilizer and nutrients—the exact formula is a proprietary secret. The trays then sit atop heat mats until roots sprout. For giant sequoias, this waiting game may take six to twelve months, whereas for redwoods it may take only two to three months.

Propagation specialists transfer branch clippings and sprouts to trays and wait several months for roots to sprout (image courtesy of David Milarch).

The team struggled for years to generate the first redwood clones. Nearly 15,000 attempts yielded three clones that survived the incubation process. “It’s bulldog tenacity and sooner of later you just break through,” says Milarch. “All we need is one to root, one to grow, one to take off.”

Once a tree is successfully cloned the first time, it is much easier to generate further clones from the juvenile material of the initial clone—success rates hover around 95 percent.

The redwood clones are expected to grow about 10 feet per year. Once mature, each tree can sequester 400 tons of carbon, the most of any conifer on Earth according to William Libby, a retired UC Berkeley professor of tree genetics.

Jake Milarch inspects redwood clones in the Archangel nursery in Michigan (image courtesy of David Milarch).

The driving force behind Archangel’s remarkable effort is Milarch’s son Jake—“He has ten green fingers,” says Milarch—and Archangel’s propagation specialist, Tom Brodhagen, the son of Dow research chemist and the grandson of a nursery owner. “Those guys could sprout Coke bottles, I swear,” he says.

“The whole rest of the world said it was impossible, but, so far, we’ve been able to do it with 75 redwoods and sequoias,” adds Milarch. “The rest of the world is batting zero.”

Congratulations to Archangel Ancient Tree Archive and all the 2013 Earth Day planting partners from the Port Orford Community Stewardship Area – home of the world’s 1st champion redwood & sequoia forest – http://www.ancienttreearchive.org/worlds-first-planting-of-a-champion-redwood-sequoia-forest/.

Earth Day 2013: Pacific High School Participates In

WORLD’S 1ST GLOBAL PLANTING OF A CHAMPION REDWOOD FOREST

http://www.pocsa.net/Earth-Day-2013-World%27s-1st-Global-Planting-of-Champion%20Redwood-Forest-Port-Orford.pdf