Evolutionary biologist J.B.S. Haldane, alluding to the enormous number of insect species roaming the earth, is often quoted as saying, “If one could conclude as to the nature of the Creator from a study of creation, it would appear that God has an inordinate fondness for beetles.” If Haldane were still alive, he and God may have spent this Memorial Day weekend glued to the Calbug project website, transcribing field notes about several of the 6.5 million bugs housed in the collections of California’s eight major entomological centers.

UC Berkeley-based Calbug is seeking citizen scientists to transcribe hand-written field notes about its 6.5 million-strong bug collection, including this beetle collected in 1833 by Charles Darwin in Tierra Del Fuego, Chile. (Image: Essig Museum of Entomology)

And they would not have been alone. Since the Calbug project officially launched last week, hundreds of citizen scientists have transcribed the hand-scrawled notes attached to tens of thousands of insect and spider specimens from all over the world.

The goal of Calbug appears to be two-fold: get people from around the world to fall in love with their bugs and use the information about where and when these critters were collected over the past century to track the course of biodiversity in the face of global climate change.

“To understand how biodiversity will respond to environmental change in the future, we must learn from their responses in the past,” says Rosemary Gillespie, director of UC Berkeley’s Essig Museum of Entomology and principal investigator of Calbug.

Gillespie hopes the transcribed records will also answer questions about which organisms are more sensitive to climate change and which tend to be the most invasive.

Citizen scientists log on

To harness the power of everyday folks interested in learning about nature while contributing to their massive-scale project, Calbug teamed up with Zooniverse. Within this highly successful online community, people from around the world can participate in projects ranging from interpreting the meaning of whale calls to transcribing old ship log to learn about historical climate data to searching for distant planets.

“Our projects help answer research questions that can only be solved by a significant amount of human attention — they require people, not computers,” said Arfon Smith, the technical lead for Zooniverse, in a statement. “People have responded in a way that is truly great. There is an appetite for contributing to something real.”

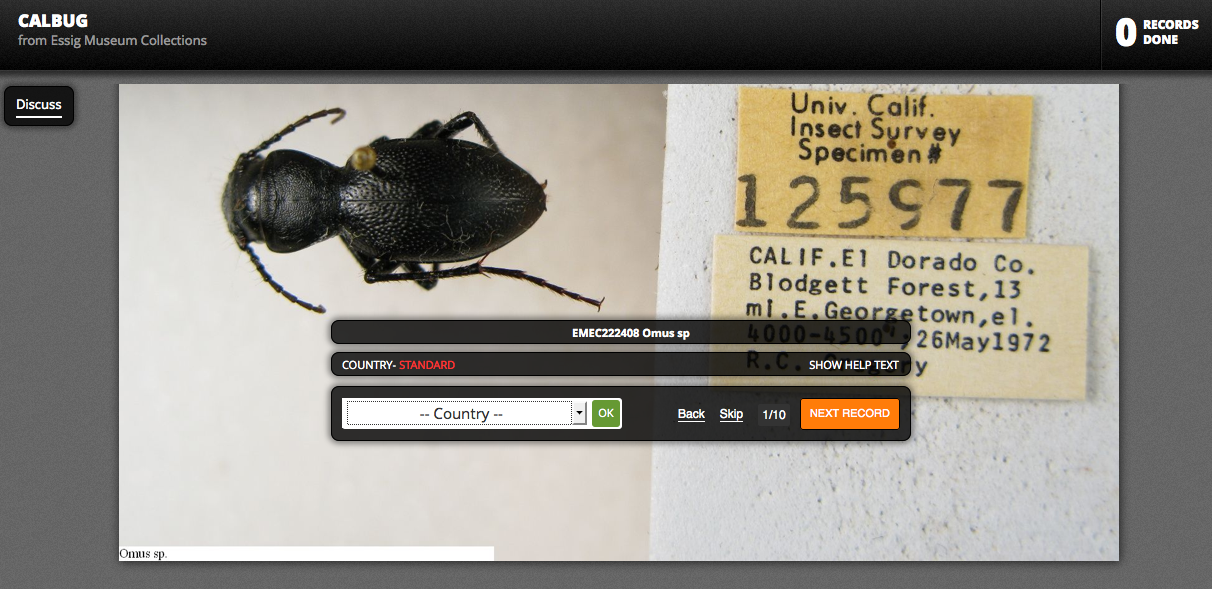

The Calbug user interface on the Notes from Nature site asks volunteers to transcribe hand-written information about where and when various insect and spider species were collected. (Image: Essig Museum of Entomology)

Calbug is hosted on Zooniverse’s Notes from Nature page, which also links to a project for transcribing records of plant specimens collected between 1880 and 2012 that are currently housed in more than two hundred herbariums. In the near future, Notes from Nature will launch a third field-note transcription project, this one from London’s Natural History Museum ornithology collection.

Terrestrial insects and spiders represent the largest volume of hidden information, says Gillespie. Conservatively, there are more than a billion specimens of these creatures in collections worldwide, and just a tiny fraction have been digitized, including Calbug’s 6.5 million-item collection. “Based on the rate we have been going, such an undertaking would take several lifetimes,” she says.

So far, nearly 2,400 Notes from Nature users have transcribed more than 120,000 bug and plant labels, including a hand-written note from Charles Darwin describing a ground beetle from Tierra del Fuego, Chile that he collected in 1833.

“We are extremely excited at the response,” says Kipling Will, a UC Berkeley professor of environmental science and policy and a co-investigator for Calbug. “This is new territory and we are pleased to be leading the way.”

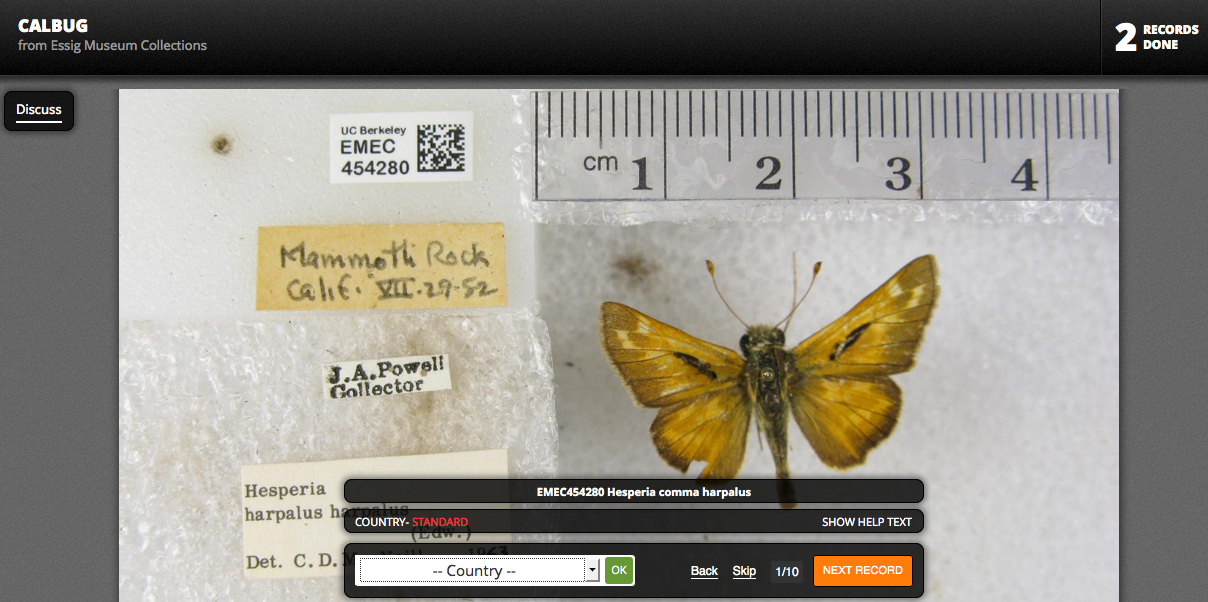

Each Calbug transcription takes a couple of minutes. Users are presented with a photo of an insect to which various field notes have been pinned. The site prompts users to enter information they can gather from the notes about country, state, county and locality – including elevation and exact latitude and longitude – as well as the date it was collected and the person who collected it.

Many of the field notes do not include all of the requested information. For example, this label for the butterfly Hesperia harpalus only indicates it was found at Mammoth Rock, Calif. A simple Google search verifies this is in Sonoma County. (Image: Essig Museum of Ent0mology)

Will says that each specimen label is transcribed three times. The Calbug team then uses an algorithm to ensure that the information from the three transcriptions matches before considering it correct.

As for the volunteer’s motivation, Will says, “I am sure that there are as many motivators as there are people.” However, in general, he cites two factors that spur volunteer to participate: the chance to contribute to science in a meaningful way the satisfaction of successfully completing a task. “Also they seem to be very curious about science in general and enjoy – as do we – the interaction with the science team via the discussion interface.”

Sarah Hinman of Albany, CA, has transcribed nearly 100 labels. “But I hope to do many more,” she says.

“I am a plant ecologist by training and a naturalist at heart so I appreciate and enjoy learning about nature in general,” adds Hinman, a UC Berkeley employee who works on projects in collaboration with the Essig Museum of Entomology. “Transcribing labels for CalBug allows me to see cool insects – and learn their names and where they are found – and contribute to a larger scientific objective.”

Great article, thanks for this. I wonder if these guys are in touch with the folks at OneZoom, the collaborative big data phylogenetic tree project.