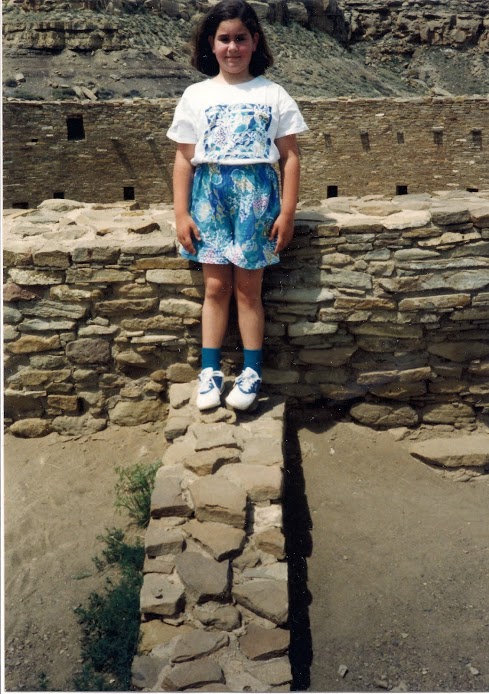

The author in 1992—age 8—at Chaco Culture National Historic Park in northwestern New Mexico. Chaco Canyon was home to thousands of Puebloans from 850 to 1250. Photo credit: Brian Sharlach.

Remember playing “The Oregon Trail” computer game in middle school? As a pioneer leading your family westward in a covered wagon, you hunted virtual deer, rabbits and bison—but not too many. You had to leave enough game animals alive to sustain your party until you reached Oregon. And along the way, you were subject to chance events such as snowstorms and snakebites, and the most dreaded fate: “You have died of dysentery.”

Yes, the game was delightfully unrealistic. But controlling the use of finite natural resources and adapting to changing conditions have been central to human survival in the American West for ages. In fact, Washington State University archaeologist Timothy Kohler and his partners in the Village Ecodynamics Project are using computer models to better understand the processes that affected prehistoric societies in the Southwest. Kohler gave an update on the project on February 16 at a symposium on long-term climate vulnerabilities, part of the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The Village Ecodynamics Project aims to solve a longstanding mystery in the prehistory of the American Southwest. Kohler refers to this puzzle as “the elephant in the room.” Ancient Puebloan peoples, also known as the Anasazi, occupied the present-day Four Corners region (where Utah, Colorado, Arizona and New Mexico meet) for hundreds of years. They cultivated corn and lived in large settlements, most famously at Mesa Verde, now a U.S. National Park and UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Curiously, nearly all the villages in the northern Southwest were abandoned in the 1200s. Patterns found in ceramics and architecture suggest the Puebloans migrated south, settling more arid regions of New Mexico and Arizona, where their descendants still live. Early tree ring analyses conducted in the 1920s showed evidence of a severe, long-term drought, which many assumed was responsible for the migration. But the dry spell is not the whole story, Kohler says. “It’s a classic problem in Southwestern archaeology, and it’s embarrassing that it hasn’t been completely solved by now. But I think we’re going to solve it. We’re very close,” he says.