Seal’s “Kiss from a Rose” and kittens with mittens, bright-colored Skittles and feeling all smitten, vibrations screaming from taut guitar strings, these are some things that I find pleasing.

I have an emotional connection with each item on that list, but only one routinely spills over into my physiology. Well, two if you count the Skittles and digestion. But the more interesting one is that high-pitched electric guitar sounds can give me goosebumps.

With the 2014 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony airing later this month on HBO, I decided to look into my love for rock’s signature squeal. This way, we can all sound like annoying know-it-alls at viewing parties should an inductee bust one out. It probably won’t be Cat Stevens.

For decades, if not centuries, scientists have known that music could prickle people’s skin, slow their breathing and kick up their pulses. But the musings on what caused these responses near the middle of the 20th Century are exactly what you would expect from a generation of psychologists reared by Victorian prudes: there was a lot of “anticipation this” and “arousal that” and “climax the other thing.”

Since then, scientists have gained access to sophisticated tools that allow them to watch our brains listen to music and better explain what’s going on. As it turns out, the post-prudes weren’t wrong.

The brains of eager listeners awaiting a particular chord, drop or breakdown can release a flood of dopamine — or “happy chemicals” as a laughter yoga instructor once told me — when the jam delivers. Musicians can take advantage of this and toy with our emotions by veering away from our expectations, making the anticipated resolution all the more climactic when they reach it.

Now, I totally buy this, but I don’t think it tells the full story of the relationship I have with my favorite guitar sounds, called harmonics. Sometimes, a harmonic that catches me off guard can be just as goosebump-inducing as one I’m anticipating. And there has to be a reason I love casinoin these sounds so much, while some people — for instance, a lot of people — don’t.

“That’s the whole point of behavioral psychology,” said Psyche Loui, a psychology and neuroscience researcher at Wesleyan University. “What gives me a specific emotional response is different from what gives you an emotional response.”

Loui, who has played the piano since she was 5 and the violin since she was 7, is interested in mapping out how pitch and rhythm elicit emotional responses in listeners. While she studies the neuroscience of music, she also investigates how emotion is communicated through speech. An upcoming paper from her group will examine how well tone deaf people pick up on emotional cues in voices.

But she’s also very interested in how personal preferences play into physiological responses to music. Loui says oodles of people experience these while listening to classical composers like Beethoven and Sergei Rachmaninoff, herself included. Not exactly the harmonic-rich riffing of a Zakk Wylde or a Claudio Sanchez my goosebumps are into, so, you know, case in point: Different strokes for different folks.

And there’s a variety in the responses themselves. Some people get chills, while others will say their heart skipped a beat. Still others feel a sensation of time slowing down. Despite all these differences in root causes and responses, Loui has seen some commonalities.

For one, people who experience these sensations appear to have greater connectivity between neurons in the audio-processing portion of their brains and their emotional centers. Further, women are more likely than men to report having them.

Mike and I circa 2001, fresh off winning the Clarkston High School Battle of the Bands. Image Credit: Mike Simpson

Of course, one could chalk this up to machismo — maybe men don’t want to talk about how sensitive they are to music. That’s not so much a concern for me talking about sounds popularized by guys like Eddie Van Halen and Billy Gibbons and the awkward latent chauvinism of 80s hard rock. Harmonics played on electric guitar are kind of like a seminude David Lee Roth doing jump splits in your ear.

That being said, harmonics are used in all types of music, even the more cerebral and widely respected genres of jazz and classical. Loui says she’ll employ harmonics on her violin if she wants to create hollow or haunting tone. Jazz musician Jaco Pastorius changed the way the world looked at bass guitars with his use of harmonics, according to my good friend Mike Simpson.

“It was like opening up a whole new realm for what the instrument could do,” said Simpson, a musician in Toronto who has played bass, drums and guitar. Traditionally, basses were utilitarian instruments relegated to low frequencies. When Pastorius started hitting harmonics, though, the instrument could taste the forbidden fruit of the upper register.

“How?” you ask. This is where I believe my love of harmonics really stems from: they’re so gosh darn scientific. When you pluck a string, it shakes up and down a little like a jump rope, fixed at both ends. This is called a standing wave. It’s a cousin to the traveling wave — the sort you’d see at the beach.

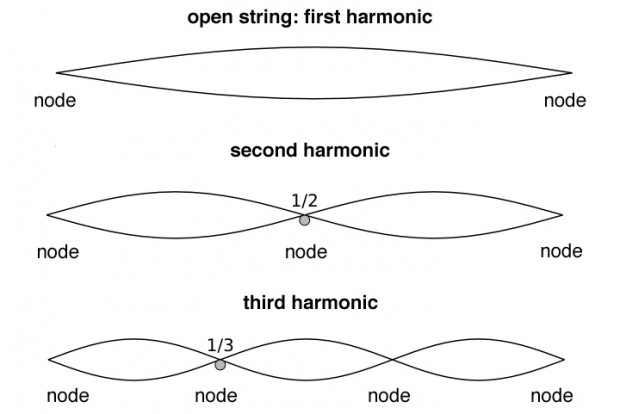

But the standing wave just wiggles up and down. The ends of the string don’t move at all. The nonmoving ends are called nodes in the language of waves. The maximum up-to-down swing region, called the anti-node, is in the middle of the string. By pressing the string against the guitar’s fretboard, you can shorten the part of the string that vibrates and make the pitch go up, but you don’t really change the shape of the wave: you still have two nodes and an anti-node.

Natural harmonics are a clever way of shifting pitch by altering the waveform. If you place your finger at a string’s halfway point, pressing gently without pinning the string to the guitar neck, you would create a third node. The string couldn’t vibrate at that point, but it is free on either side of your finger. You’d now have three nodes and two anti-nodes. The resulting sound is double the frequency of the open note, making it a full octave higher.

You can pull a similar trick with a gentle press at a third of the string’s length. To preserve the symmetry of the wave, another node will appear two-thirds of the way down the string (it also works in reverse, you could put your finger at the two-thirds point). With four nodes and three anti-nodes, this harmonic is triple the frequency of the open note.

The harmonics that really squeal, called pinch or artificial harmonics, are the slightly more complicated, but the premise is the same. You cram more nodes into the waveform to wail at higher frequencies.

Getting back to musical expectations and fulfillment, a harmonic can often be the expected note, just at a higher rung on the music staff. So does it violate expectations or satisfy them? Is it a musical surprise or a resolution? Maybe it’s both; maybe it’s neither. Simpson said he thinks of them as points of emphasis or flourishes.

I like to think that some of my chills come from these curiosities. I also love thinking about how the physics of a simple guitar string can be so useful in understanding quantum mechanics. Questions and answers all tied to a string, harmonics are most definitely radical things.