PHOCASing on the Positive

Tunu, an Alaskan spotted seal who has never experienced the wild, works alongside human scientists to save his wild counterparts, Elise Overgaard reports. Illustrations by Julia Ditto and Charin Park.

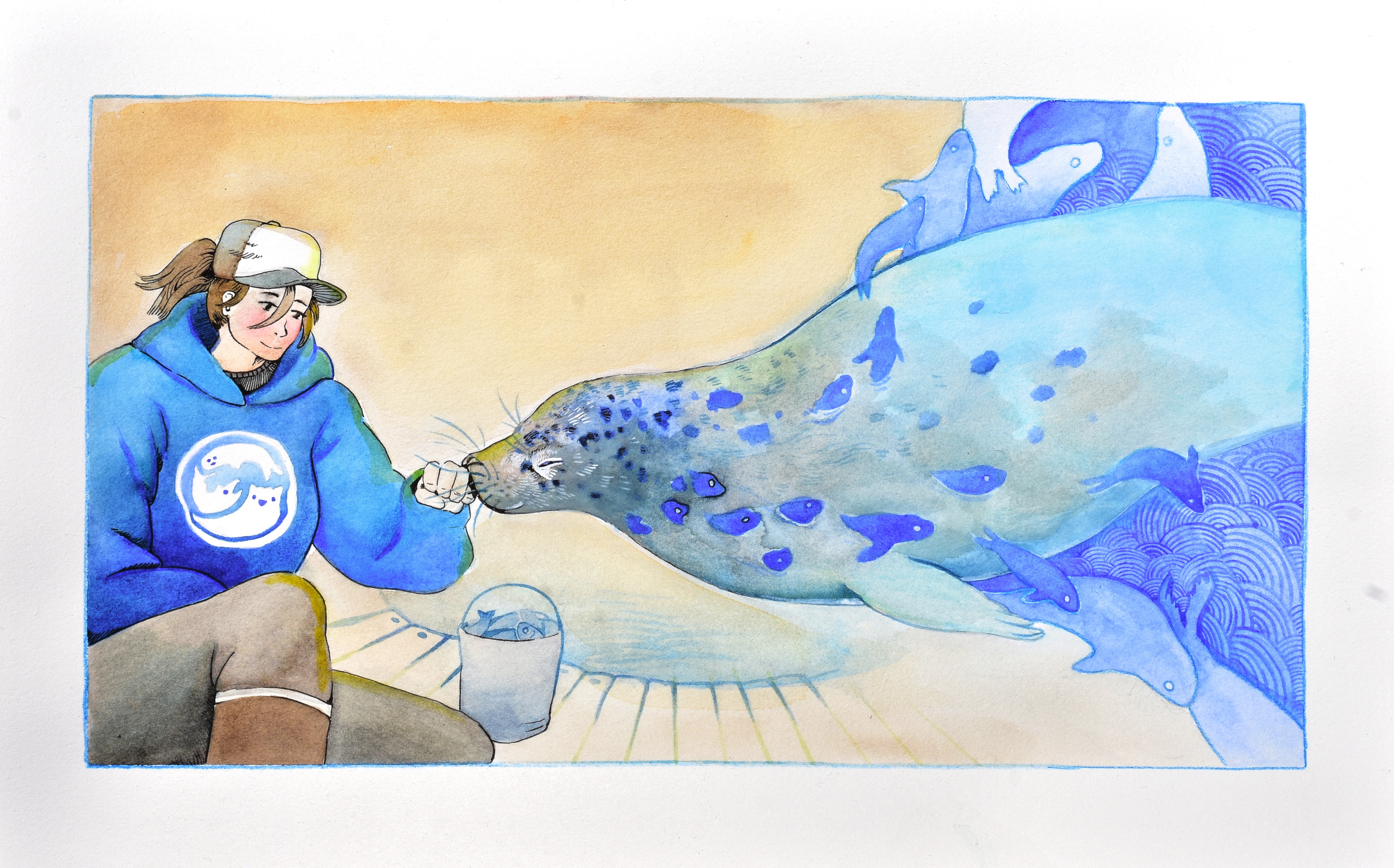

Illustration: Charin Park

Tunu, an Arctic spotted seal, galumphed to the edge of the pool. His flippers hovered above the ground as he bounced on his belly, inch-worming toward the water. Progress was slow — he covered just a few inches per bounce — but finally, he slid into the water.

In the pool Tunu transformed into a graceful, athletic acrobat. His silvery coat, dotted with dark spots, shimmered in the bright California sunlight as he twirled and slid through the water. Spotted seals don’t normally live in Santa Cruz, but Tunu was thriving in the icy cold water pulled from the depths of Monterey Bay.

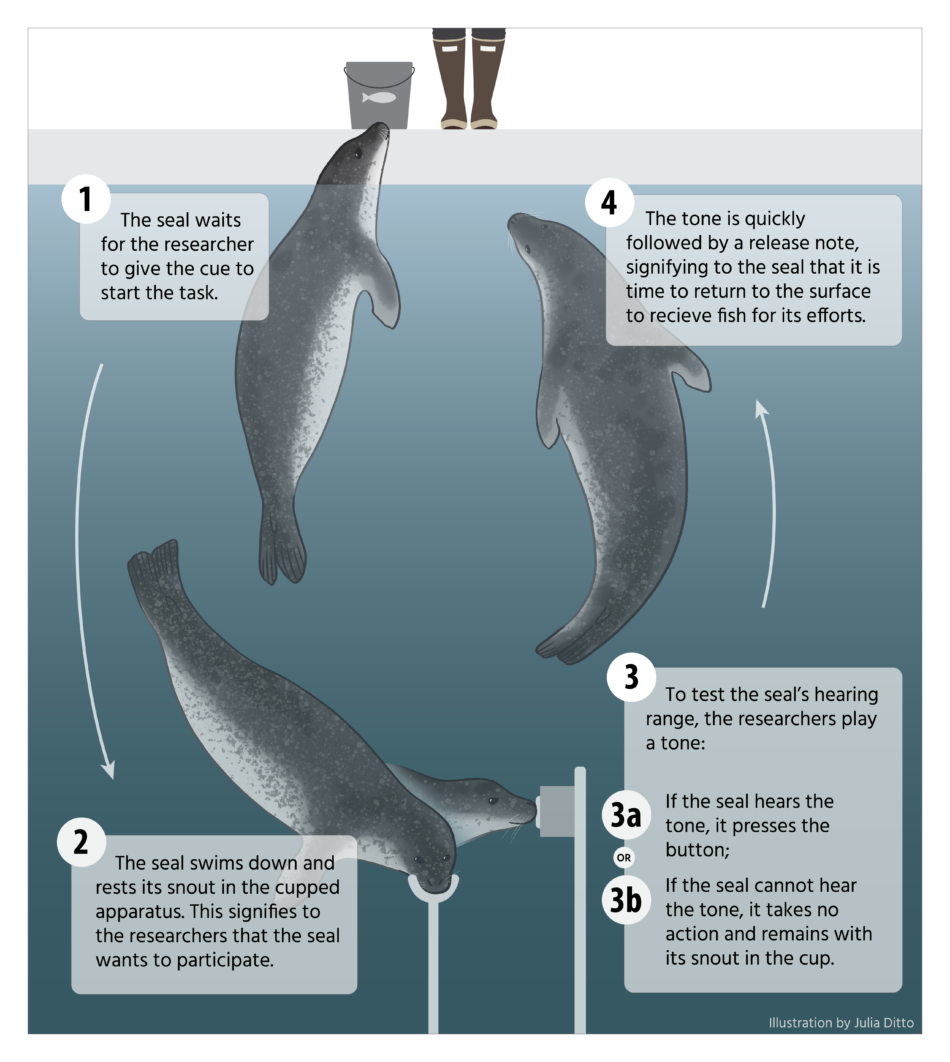

Tunu stopped with purpose at the edge of the pool, where a trainer wearing a navy hoodie, a knitted cap and a pair of weathered Xtratuf boots awaited. Tunu had arrived at his office and needed to decide whether or not he wanted to work. He indicated his consent by making an elegant turn, diving to the bottom of the pool and resting his head in a white plastic cup shaped to hold a seal snout, as he was trained to do. Every muscle in his body was still. He waited.

Suddenly, a beeeeeeep rang through the water. Tunu swung his head around, tapped a sensor with his nose, then raced to the surface to collect his fish reward. He had logged another data point in one of his many science projects — he had communicated to his trainer that he could hear underwater tones at 800 hertz.

A seal with a science job

Tunu has lived an unusual life. His journey — from Alaska to California and back to Alaska — has taken him to places that others of his kind will never see. One of only a handful of spotted seals in captivity in North America, Tunu is a life-long resident and a cornerstone of Colleen Reichmuth’s research program.

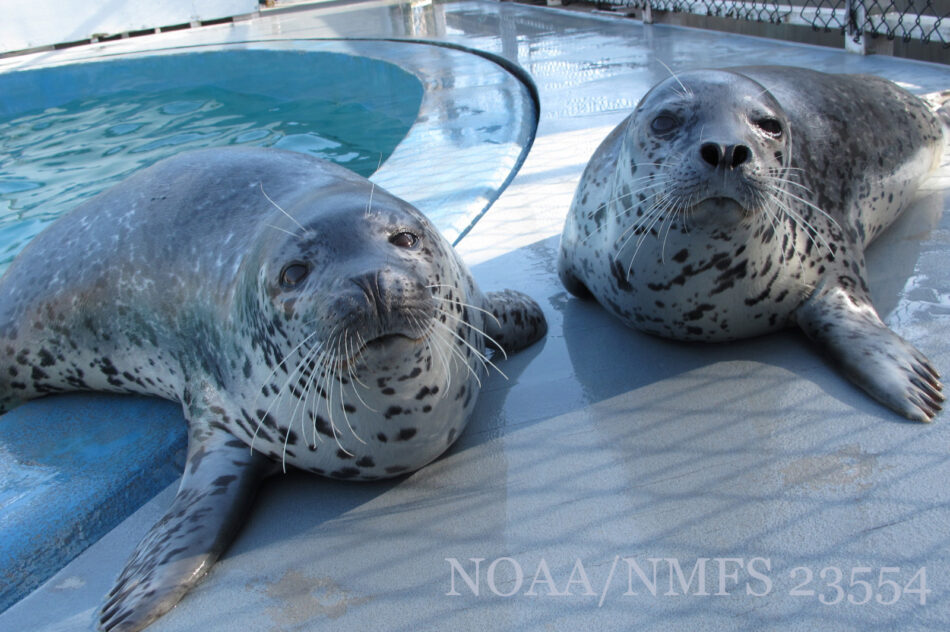

Colleen Reichmuth and Tunu take a break from training at the Alaska SeaLife Center in Seward, Alaska. Photo: M. Meranda (NOAA/NMFS 23554)

Reichmuth, a research scientist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, is a behavioral scientist — she trains rescued animals that can’t be released back into the wild to participate in scientific research. Her project’s name, Physiology and Health Of Cooperating Arctic Seals, or PHOCAS, is a play on the spotted seal’s scientific name, Phoca larga, and also a nod to Reichmuth’s signature research style — voluntary cooperation between seals and scientists on research projects.

“It’s the difference between thinking about doing research on animals and doing research with animals,” said Reichmuth. “We really consider the animals as our partners.”

“The story for me is that individuals matter — the life of one individual animal can be incredibly meaningful,” said Reichmuth. “What we’re able to learn from Tunu can shine a light on our understanding of this entire species.”

Through this partnership, the team has amassed information about the enigmatic sub-arctic spotted seal species — information that nobody could obtain in the wild, and information that could help wild populations succeed as climate change and human activity threaten their lifestyles. The project is ongoing, but conservation and management organizations like the Arctic Ice Seal Committee and the National Oceanic and Atmosphere Administration, or NOAA, already use Reichmuth’s results to inform their decisions.

“The story for me is that individuals matter — the life of one individual animal can be incredibly meaningful,” said Reichmuth. “What we’re able to learn from Tunu can shine a light on our understanding of this entire species.”

An unexpected beginning

Tunu’s life began in turmoil in a tiny town in northwestern Alaska.

In April 2010, subsistence hunters in Tununak, Alaska, captured and killed a spotted seal before realizing the seal was pregnant. The hunters delivered the pup, then sent him on a bush plane — the only way to traverse more than 500 miles of wild Alaskan terrain — to Anchorage in a box.

Tunu was lucky to be alive. Spotted seal pups are valuable resources for Alaska Natives, and they aren’t often rescued. But he was also unlucky. Each year, the Arctic Ice Seal Committee decides how to handle rescued ice seals. At that time, and still today, rescued ice seals are automatically deemed non-releasable — they must remain in captivity for life. Tunu would never know the Alaskan seascape.

From Anchorage, scientists drove the hungry 14-pound pup through the mountains to the Alaska SeaLife Center in Seward. There, Tunu doubled his weight and learned how to hunt fish in a pool.

Tunu as a pup at the following his rescue at the Alaska SeaLife Center in Seward, Alaska. Photo: Alaska SeaLife Center Marine Mammal Rehabilitation Program (NOAA/NMFS Stranding Agreement)

In September, the Alaska team loaded Tunu onto a freight plane in a crate. Reichmuth, who had arranged for Tunu to join her research program in Santa Cruz, California, hopped into a jump seat behind the pilot.

In the air, Reichmuth got up to check on Tunu frequently. Reichmuth knew how to care for big marine mammals — she’d worked with elephant seals, walruses, even Stellar sea lions. But Tunu was her first Arctic ice seal, and moving an ice seal to California was risky. She wanted everything to go right. While Reichmuth took feverish notes on Tunu’s vital signs and health status, Tunu napped in the cold, dark cargo hold to the low-frequency hum of the airplane engine.

In Santa Cruz, the excited California team welcomed Tunu and kept watch as he explored his new habitat — an outdoor seawater pool on the coastal bluffs of the Long Marine Lab. They checked on him every hour throughout the first night.

Reichmuth had a plan for Tunu, and he started training the next day.

The case for conserving ice seals

Tunu is a spotted seal, one of four species of Arctic ice seals. Spotted seals are around five feet long, weigh around 200 pounds and have distinctive spotted coats. Ice seals occupy the northern Pacific Ocean, from Alaska to Japan, and are built for Arctic living, with a hefty layer of blubber — up to two inches thick in spotted seals — impressive claws for grasping onto ice and plentiful stiff whiskers for sensing food in dark, icy waters.

Michael Cameron, program manager for NOAA’s Polar Ecosystems Program, said ice seals, which are protected by the Marine Mammal Protection Act, play critical roles in their Arctic ecosystems. He said conserving the seals is important for both the ecosystem and the humans that rely on them. Ice seals eat fish, krill and squid, and occasionally get eaten by polar bears, orcas and even walruses. They are also vital cultural resources for coastal Alaska Native communities, who hunt them for food and use their skins for clothing, equipment and traditional crafts.

“The work that Dr. Reichmuth and her colleagues are doing is invaluable to helping the mission to collect data that helps managers to help to protect and conserve the species,” he said.

Ice seals rely on their sense of hearing to hunt and communicate with each other in dark Arctic waters. But human-caused noise from shipping and industrial activities is increasing at a rapid pace, making hunting and communicating harder.

Scientists don’t know much about how ice seals perceive sound, and it’s hard to set limits on human-caused noise without that information. But Reichmuth knew Tunu’s arrival in Santa Cruz was an opportunity to change that. Reichmuth devised a way to ask Tunu, ‘can you hear this sound?’ To collect the data, she needed Tunu’s cooperation.

Bioacoustics in California

If your doctor was testing your hearing range, they’d say, “Please sit still, listen for the tone and push the button when you hear it.” That’s hard to explain to a seal, but Reichmuth and her team taught Tunu how to do it.

“Everything comes from this positive base…You are really paying attention to what makes animals feel safe, comfortable, nourished, have their needs met, to be interested, engaged,” said Reichmuth. “There is a math to it, but it changes for every individual.”

Reichmuth uses positive reinforcement methods. Focusing on the positive — or PHOCASing, as the team likes to say, recalling the project’s name — builds trust between both animal and human teammates, and it’s the heart and soul of Reichmuth’s program. She said that when she’s working with an animal (or a human) she asks, “What is the thing that is really going to light them up?”

“Everything comes from this positive base…You are really paying attention to what makes animals feel safe, comfortable, nourished, have their needs met, to be interested, engaged,” said Reichmuth. “There is a math to it, but it changes for every individual.”

Just like humans, each animal has an individual temperament and characteristic behaviors. Tunu likes to spin as he swims laps. He sometimes does inversions in the pool, with his head underwater and his back flippers sticking up in the air. And he likes to rock his body back and forth, gaining momentum until he nearly stands upright on his back flippers. His trainers are acutely attuned to Tunu’s likes and dislikes, and they work constantly to use that information to improve their relationships with him.

Tunu caught on to the hearing task and, by 2014, showed that he could easily hear frequencies from 0.6 to 11 kilohertz in air and from 0.3 to 56 kilohertz in water. His hearing was quite sensitive in both air and water, and it surprised the scientists. For reference, humans hear sounds from about 0.2 to 20 kilohertz in air.

Next came a real-world application. Ocean surveyors use seismic air guns to explore oil and gas deposits underneath the Arctic seafloor. Air guns make big underwater sound waves, creating a noisy background that could make it harder for seals to communicate. So the team added air gun sounds to Tunu’s hearing trials, asking, “If the environment is noisy, can you still hear this sound?”

By performing the same task with air gun sounds blasting alongside the beeeeeeeep signal, Tunu told the researchers either, “Yes I can still hear it,” or, “Nope, can’t hear it now.”

NOAA will consider those results as they set limits for using seismic air guns in the Arctic.

A changing seascape

After 5 years in Santa Cruz, Tunu had a new project. But he needed to be in Alaska. The California team said goodbye, Reichmuth again accompanied him on the airplane and the Alaska SeaLife Center celebrated his return. They hadn’t seen him since he was a pup.

The new project revolved around ice and energy.

As their name implies, ice seals need ice. Ice seals “haul out,” or move from the water onto solid chunks of ice, to birth, nurse and raise their pups, and both males and females haul out for an annual molt when they shed their fur and grow a fresh new coat — activities that are impossible to do in the water. Different species of ice seals need different types of ice. Spotted seals like Tunu need sea ice — the kind that just floats in broken pieces on the ocean’s surface.

But sea ice is melting. Ice seals have to travel farther and work harder to find it. That extra work costs energy, and if they can’t find ice at all, they can’t birth healthy pups or molt. If they can’t molt, they may be stuck with a gunky layer of skin and fur, which could cause health problems.

NOAA recently declared two “unusual mortality events” — unexpected strandings or significant die-offs — for ice seals. One lasted from 2011 to 2016 and affected at least 657 seals. The other lasted from 2018 to 2022 and affected 368 ice seals. The causes are still unknown, but many seals had skin lesions and infections related to abnormal molts.

For Reichmuth, the events were a call to study molting physiology. “When this began, all they knew was we’re seeing more sick animals than we expect. But we don’t know what the biology of a healthy animal is,” said Reichmuth. But she had Tunu. She could establish what molting looked like in a healthy animal, and maybe help figure out what was happening in the wild. Tunu and Reichmuth got to work.

Physiology in Alaska

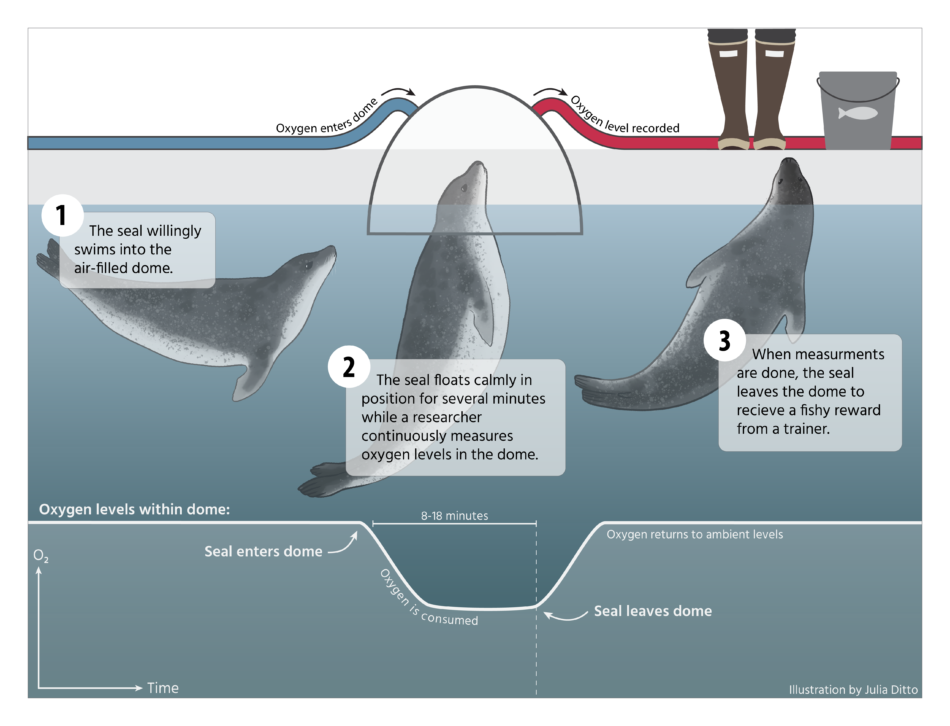

On a cold February morning in 2023, as the first daylight flitted across the tops of the snow-covered mountains surrounding the Alaska SeaLife Center, Tunu dove into his pool and got ready to work. He stationed himself under a floating plastic dome, with his head in the air and the rest of his body floating in the water. The dome allows the researchers to measure how much oxygen Tunu uses while he rests calmly in the water.

Tunu remained still while snowflakes fell silently from the indigo sky onto the dome. The fog on the dome waxed and waned as Tunu breathed quietly. The only other sound was the squeak of the trainer’s Xtratuf boots as she shifted her weight. A full thirteen minutes later, Tunu swam away from the chamber, splashed around the pool and collected a big fish reward.

The task showed the research team how much energy Tunu used per minute while resting in the water. They are also investigating how much energy Tunu uses to swim and dive in the pool, and to rest while hauled out. The information the team gathers through these studies will help them to predict how much extra energy it costs a seal to travel farther to find ice, or to survive if they can’t find ice at all.

“It’s not a normal life for a spotted seal,” said Reichmuth. “But it has led to this great series of adventures that taught us so much about his entire species.”

Energy costs and hearing ranges aren’t the only spotted seal “normals” that Tunu has helped to establish. The PHOCAS team could tell you what Tunu ate for lunch on February 12, 2014, or what his body measurements were every April for the past decade. They’ve tracked the development of his “voice” through puberty and his swimming habits. The massive collection of details about Tunu has helped them to establish all kinds of standards for spotted seals — from vocalizations during mating season to feeding mechanics to normal blood panels. Tunu and Reichmuth literally wrote the book, contributing the first section on spotted seal health to the CRC Handbook of Marine Mammal Health — the one book every marine mammal practitioner has, according to Reichmuth.

“It’s not a normal life for a spotted seal,” said Reichmuth. “But it has led to this great series of adventures that taught us so much about his entire species.”

Posing for aerial picture day

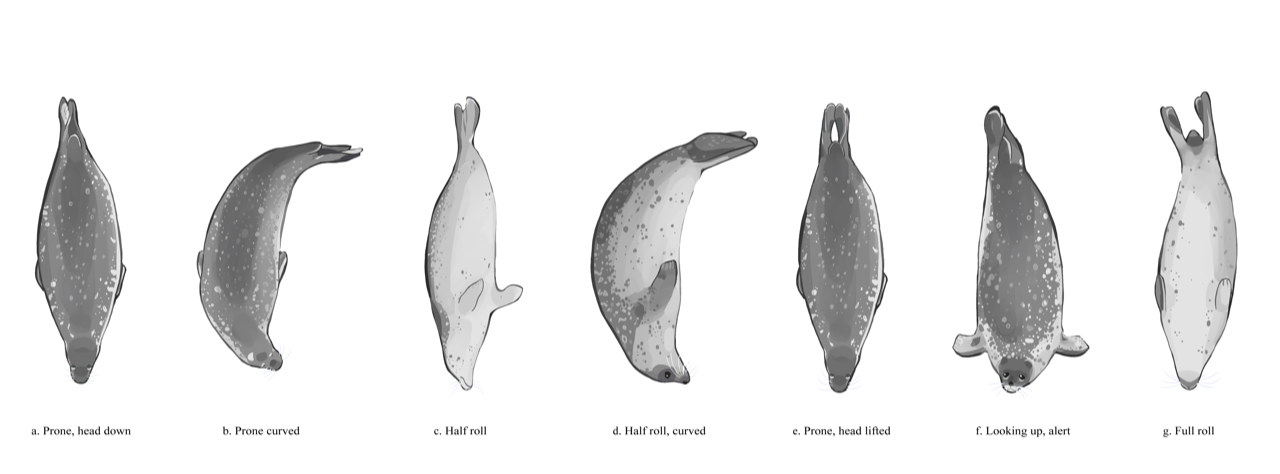

Recently, Tunu used his skills to help Cameron and his team at NOAA. Noisy seas and ice loss are threats, but NOAA doesn’t know enough about wild spotted seals to say how much danger they’re in. It’s really hard to count wild seals and assess their health from the air, one of the few ways NOAA can study Arctic seals. Cameron needed something to compare his aerial photos to, and Reichmuth could provide trained animals with known weights and body measurements to sit still in specific poses.

So Reichmuth’s Alaska team taught Tunu to, well, act like a wild seal. At a trainer’s command, Tunu laid flat on his belly on a platform next to his pool at the Alaska SeaLife Center with his head resting on the ground. The trainers issued a suite of commands: Tunu raised his head into the air — like he was looking up in the sky at an airplane — then flopped over onto his back with his belly up in the air, then laid on his side, then allowed the trainer to physically manipulate his body into a ‘C’ shape that many wild seals rest in.

Tunu held each position for minutes at a time while NOAA pilots flew unmanned drones over the platform and snapped photos of Tunu from up to 200 feet in the air. The photos will help NOAA researchers to better assess the health and condition of wild spotted seals over time and to decide whether the seals meet the criteria of a threatened species.

Opening the door for ice seal research

Reichmuth’s job isn’t always easy — caring for large marine mammals is a round-the-clock commitment, and both seals and humans sometimes have bad days. If Tunu doesn’t feel like working, the team doesn’t collect data that day, making it tough to anticipate experiments and meet scientific deadlines. But Reichmuth said she and her team survive tough days by, again, focusing on the positives.

Her program has expanded to include more spotted seals as well as other species — ringed seals and bearded seals, which are even more reliant on sea ice than spotted seals. But Tunu got the whole program started, and Reichmuth is grateful. “Without Tunu at that moment in time, maybe none of the rest of this story would ever have happened,” she said.

In February 2023, back at the Long Marine Lab in Santa Cruz, Reichmuth, sporting waterproof boots and a black Patagonia fleece sweater, stood on the deck of Tunu’s old research pool. Noatak, a bearded seal more than twice the size of Tunu, clambered out of the pool and galumphed over to meet her. Noatak’s cautious black eyes locked on to Reichmuth’s kind, icy blue eyes and they both held steady, assessing each other. The air between them was relaxed and comfortable, but focused. Reichmuth gently laid her hand on Noatak’s back. He didn’t flinch. On Reichmuth’s signals, Noatak raised each flipper, touched his nose to Reichmuth’s hand, then rolled from his belly to his back.

“Good boy,” said Reichmuth, her voice soothing but encouraging and appreciative of his cooperation, as she passed him a fish. Noatak, she thinks, could do for bearded seals what Tunu has done for spotted seals.

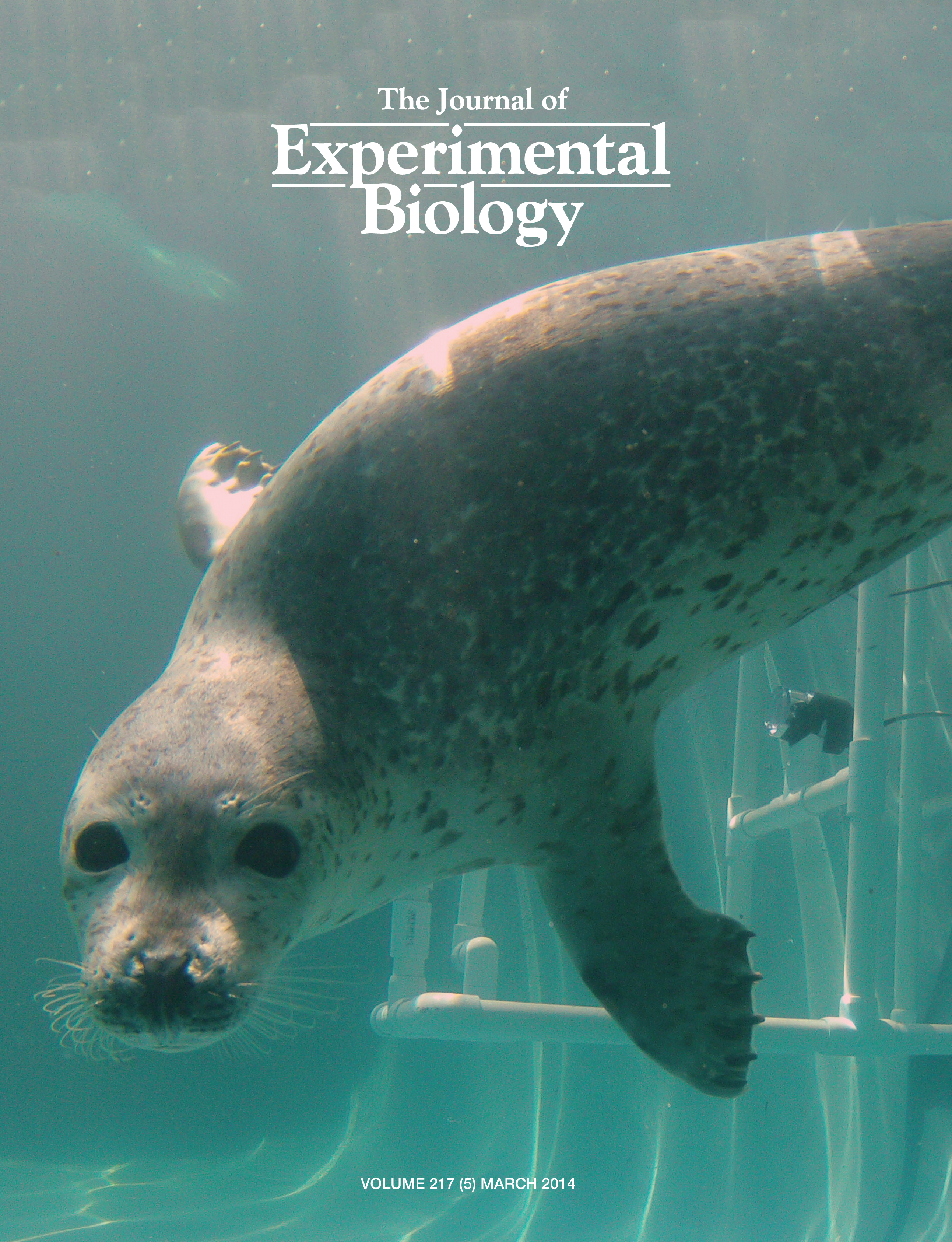

Tunu, pictured with the underwater bioacoustic experimental equipment in the background, made the cover of the March 2014 issue of The Journal of Experimental Biology.

Back in her office, surrounded by stacks of printed journal articles, thick biology books and hand-drawn pictures of seals, walruses and otters — artistic contributions from past students and her own children — Reichmuth reflected that Tunu’s success makes caring for marine mammals for their entire life, and much of her own, worth the incredible effort. “Having the chance to work with him and learn about him and really raise this young animal up was a magical experience,” she said.

Reichmuth pointed out a 2014 scientific journal tacked to her wall that featured a cover photo of Tunu. She reflected on Tunu’s journey from an unlikely rescue to “college” at UCSC to doing science in Seward. Although Tunu has never experienced the open ocean, he’s contributed to 18 scientific publications so far, each one containing information that could help to save his wild counterparts. It’s a stark difference from Tunu’s other possible fate the day he was born. “Would Tunu’s life have been better off just disposed of, as opposed to this strange but wonderful adventure that he has had?” she asked.

Author’s Note

Tunu was not alone on his journey. In the same week as Tunu’s rescue, the Alaska SeaLife Center team also rescued an abandoned newborn spotted seal pup — later named Amak, the Inuit word for “playful” — from King Salmon, Alaska. From that time on, Tunu and Amak never parted.

Tunu and Amak hang out by the pool at the Alaska SeaLife Center in Seward, Alaska. Photo: Alaska SeaLife Center (NOAA/NMFS 23554)

The pair learned to hunt together, competing for fish in the SeaLife Center’s pools. They traveled to California and adapted to their Santa Cruz home together. The lifelong companions matured into adulthood, learned how to perform research tasks, and traveled back to their Alaskan home together. Having one spotted seal made Reichmuth’s Arctic ice seal research interesting, but having two males of the same age with the same upbringing gave her statistical power, experimental controls and confidence that her findings weren’t anomalies. More ice seals — spotted seals Kunik and Sura, bearded seals Noatak, Saktuliq and Siku, and ringed seals Nayak, Natchek, Pimniq and Dutch — have joined Reichmuth’s program over the years, but Tunu and Amak kicked everything off. In 2020, the pair celebrated their tenth birthdays together.

Tunu and Amak were rescued in the same year and grew up together. They spent their lives together in Reichmuth’s program until Amak passed in 2020. (NOAA/NMFS 23554)

Sadly, later in 2020, Amak suffered an unforeseeable and fatal medical emergency. Amak’s sudden death was a painful blow to the trainers and researchers who cared for him daily and had watched him grow from a pup to a mature and highly-trained seal. Unfortunately, due to time and space constraints, it was not possible to include Amak in the main story, but his many contributions were critical to the program’s initial success and were recalled lovingly by many of the sources that contributed to this story.

© 2023 Elise Overgaard / UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

Elise Overgaard

Author

Ph.D. (biomolecular science) Boise State University

B.S. (human physiology) Boston University

Internships: Symmetry Magazine, Monterey Herald, Stanford News Service, SLAC National Accelerator Lab

At ten years old, I published the Country Kids Club Newsletter, a monthly chronicle of Weiser River Road’s activities. I assigned stories to the neighborhood kids at meetings in our tree fort by the creek. We investigated urgent news: the cool rocks Willie found, the cougar that chased Mikel, the mystery of Ana’s extra-large pumpkins. With mad Microsoft Publisher 97 skills, I arranged reports into a printed newsletter. I made it easy for readers to find kitten updates by including discrete sections and a table of contents.

My zeal for disseminating information was matched only by my curiosity. I chased an education in science, becoming a biomolecular researcher myself. Along the way, I retained my passion for sharing discoveries, and for constructing well-organized documents. With science communication, I’ve married all of my loves at once.

Charin Park

Illustrator

B.A (Creative Studies Biology) University of California, Santa Barbara, California

Internship: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Creative Studio

My first love was shorebirds – bright carnelian beaks and stilted feet that first filled me with wonder. Then, in high school, I got busy measuring nematodes every summer, in hopes of gaining insight into marine body-size evolution. Majoring in biology at UCSB took me to a remote oil rig—Platform Harmony—to study the rockfish flourishing in its cold, nutritious waters. And then it took me to the Canadian arctic. Studying ecology has brought me on amazing adventures. It has pounded humility into me, made me aware of my intimate connections to places, creatures, people I’ve never seen. But behind the scenes, I was always painting and drawing. Choosing just one field to specialize in was a confusing experience when the world offered so much beauty, so my advisor recommended a different path for me. Now, one month before beginning Science Illustration, I am ready for a new journey.

Julia Ditto

Illustrator

B.S. (environmental science, outdoor studies minor) Alaska Pacific University, Anchorage, AK

Internship: North Cascade Glacier Monitoring Project

Creating visuals help me process, remember and share information. From a young age, I’ve been inspired by scientific infographics— drawings and diagrams often freckled my school assignments.

In college, I learned that science and art could be combined in one career, and I used illustration to communicate field research. I studied glaciers, flora and climate change in remote areas of Alaska. I joined a series of expeditions across the Brooks Range, where I carried a watercolor kit over 1,500 miles to illustrate the climate-driven changes occurring in the Arctic. These experiences allowed me to meld my passions in art, wilderness travel and scientific inquiry. Field sketching became an integral part of my scientific process, providing an opportunity to observe and connect with the natural world.

I believe art and science are more compelling together rather than separate; art can be precise, just as science can be beautiful.

I enjoyed reading and learning about Tuna adventures.