I started writing this post when I discovered one of my fittest friends, Rick*, a 50-year-old Ironman triathlete and veteran marathoner, has a surprisingly unfit heart. So unfit, that he didn’t show up for the Sunday morning run, a ritual rarely missed in our running community unless there’s a race to attend or a death in the family. As it turned out, both of those events—a race and a death—did happen that day. Thankfully, not to Rick. But it may have been only a matter of time before those words applied to my friend.

Devastatingly, a 43-year-old athlete from Texas did lose his life during a race on Sunday. Ross Ehlinger died shortly after he jumped off the ferry and into the San Francisco Bay at the start of Escape from Alcatraz triathlon, according to news reports.

Until now, no one has ever died in the popular endurance event in which athletes swim 1.5 miles, bike 18 miles, and then finish with an eight-mile run. Preliminary race reports attribute Ehlinger’s death to sudden cardiac death (SCD), a syndrome that’s gaining attention among sports medicine physicians and cardiologists.

Although heart-related fatalities aren’t common in endurance events—

30 swim-related fatalities were blamed on SCD in races from 2003 through 2011 according to a 2012 USA Triathlon study released in October 2012— even one death is too many.

Among 10.9 million marathoners, a 2012 study published in the New England Journal Of Medicine found 59 cases of cardiac arrest with 42 fatalities, an incidence rate of .54 among 100,000 participants.

But the rigorous training it takes to compete in these events may contribute to heart disease and sudden death in athletes, according to Abbas Zaidi and Sanjay Sharma in the January issue of Future Cardiology. In their article “Exercise and heart disease: from athletes and arrhythmias to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and congenital heart disease,” the authors note higher fitness levels may mask developing heart disease and make abnormalities hard to find with routine testing. Continuous training regimes also contribute to progressive, irreversible heart damage in older competitors. So, competitors may unwittingly over-exert weakened heart muscle, leading to sudden death.

It may also be more shocking when hearts fail athletes such as Jim Fixx, the author of The Complete Book of Running, who died at 52 of a massive heart attack. These are people who make an effort to be healthy. Shouldn’t their hearts be as sturdy as the other muscles that propel them through endurance events?

It may be that many of these competitors don’t have healthy histories. They kicked their smoking habits, got off the couch, and laced up their running shoes to become a cardiac bomb ticking at a ten-minute pace. Their newly-minted muscles still harbor their old medical risks. Fixx was one of those people. Ray Sierengowski, is another worrisome example; the 39-year–old from Kalamazoo, Michigan, told a San Francisco Chronicle reporter he trained for 10 months, lost 90 pounds, and was shocked he finished the Alcatraz triathlon.

But that’s not Rick’s problem. It’s mine. I smoked for 20 years, and then discovered life in the active lane when I moved to Santa Cruz. After I signed up for a women’s triathlon training group, I never looked back unless I thought someone was gaining on me. Sport specialists have analyzed my running stride, found my maximum heart rate, and tested the oxygen-carrying capacity of my lungs. But, no one ever suggested checking the blood flow from my arteries into my heart.

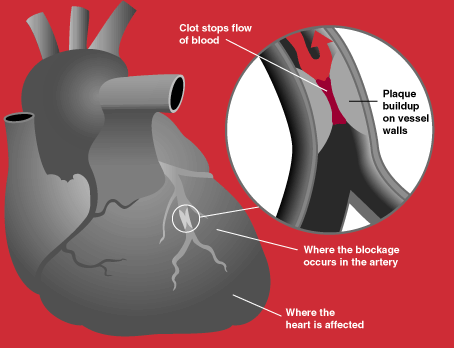

It turns out the condition of those arteries can be critical in older athletes. Studies show blockage in coronary blood vessels cause more sudden deaths in over 45-year-old athletes. Blood can’t get to the heart, no matter how hard it pumps. Men are at more risk than women.

In younger competitors, SCD is more likely to be caused by an abnormally thickened heart muscle, a condition called hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The thickened heart walls are less efficient and leave less room for blood to flow the four chambers of the heart.

Rick was lucky. When he ran a 10K two weeks ago, he says he didn’t feel well even though he won his age group. He chalked it up lingering effects of the flu. Then he started having odd pains in his chest.

A quick trip to the doctor turned into a series of appointments for Rick. His blood tests came back normal. He didn’t have high cholesterol or low blood sugar. The pattern of electrical activity in his heart looked normal. But then he flunked the treadmill test—although he ran at the machine’s fastest speed before he failed.

His doctors promptly put a catheter in his leg vein, snaked the line up to his heart, and injected a substance that highlighted his blood vessels. Finally, the doctors could pinpoint his problem. The main artery to his heart was clogged with plaque and only 10 percent of the blood from his lungs was getting into his heart. Cardiologists call the condition a “widowmaker.” Not a comforting nickname for your coronary artery.

Rick was lucky. If he hadn’t felt lousy during his race, he might not have gotten a thorough cardiac workup in time to save his life. Now there’s a stent in his artery, a honeycombed scaffolding lining the vessel wall to prop it open. With continued luck, that stent will stay with him for the rest of his long life. The doctor cleared Rick to return to running within weeks.

While race directors routinely remind competitors to train appropriately for events, they can’t check every athlete’s training log. And even if it was possible to run a pre-race EKG on every athlete, it isn’t clear this test could catch every hidden heart condition. But, it could catch some. Maybe the first line every athlete should toe up to is at their doctor’s office. I know I don’t want my finish line to come too soon.

#####