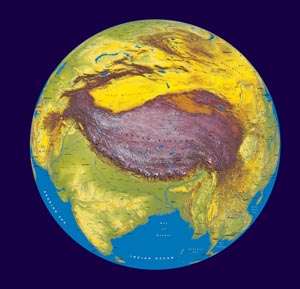

Tibet is the Higher Ground, Part III, 2009, by Newton and Helen Harrison, is on display at the Sesnon Art Gallery at UCSC through March 15.

Environmental art pioneers Newton and Helen Mayer Harrison have an exhibit at UC Santa Cruz’s Sesnon Gallery this quarter. It’s part of a larger focus on environmental art, including a series of lectures on Wednesday nights. I’m in Mountain View on Wednesdays and couldn’t attend the lectures, but the guests are an intriguing mix of artists and scientists.

A recent visit to the exhibit got me thinking, what is “eco art” anyway? If scientists are communicating with the public about their work and artists are contributing to scientific research, where exactly are the boundaries between art and science?

When I visited, the piece that moved me the most was the oversized “Tibet is the High Ground, Part III, 2009.” It’s part of a series that draws attention to the drastic changes our planet will undergo as climate change progresses. On a distorted map of Asia, an oversized Tibet squeezes out India and China. Along the edges of the image, text explains how Tibet’s glaciers feed many of India and China’s river systems. Overuse and a warming climate are depleting the water available from this valuable resource.

The Harrisons are also well-known for their large installations, like “The Endangered Meadows of Europe,” where they relocated a 400 year-old meadow slated for urban development to a museum rooftop. They collaborate extensively with scientists, community groups and government agencies to pull these installations off.

Some of the Harrisons’ maps reminded me of infographics in the best science news stories. The lyrical commentary makes it clear their work lies in the realm of art, though. As artists, they have the liberty to go beyond the conclusions scientists can draw from the evidence. For example, they use the most extreme sea level rise estimates in the series, “Peninsula Europe” to create their dramatic images of a continent flooded by rising oceans. I suspect they’d be risking their credibility, too, if they went too far.

This blend of art and science intrigues me. Art that speaks to our social and environmental concerns has been around at least since the 1960s. The phrase “eco art” is a relatively new one and its meaning is up for debate.

Gillermo the Golden Trout by Andree Singer Thompson, an example of eco-art, on display at its home at the Richmond Art Center in Richmond, CA

I first ran across the idea at Laney College where I edited the student newspaper before coming to UCSC. Andree Singer Thompson teaches a class called Eco Art Matters and I’ve liked her installation, “Guillermo the Golden Trout,” (also focused on water resources, this time in California) ever since she showed me photographs. At some point, I want to see it person at the Richmond Art Center in Richmond, CA.

An upcoming project that’s gotten a lot of press is Stephen Glassman’s plan to convert urban billboards into an elevated bamboo garden, called Urban Air. His Kickstarter campaign raised over $100,000 for the prototype in western Los Angeles, where Glassman lives and where I spent part of my childhood (Floating bamboo trees would have tickled the junior high version of me). The gardens will be equipped with air quality monitors which would send data by WiFi to a central hub.

An artist’s rendition of what the eco-art installation, Urban Air, by Stephen Glassman, will look like on the frame of a Los Angeles billboard.

What ties all these projects together? What makes it Art instead of good-looking science experiments? Eco artists can draw on a deep well of emotion in a way scientists usually can’t. They draw attention to environmental problems, and the more ambitious ones try to fix some of them.

This doesn’t mean scientists shouldn’t engage with the public themselves. Most (though not all) people understand the scope of the climate change problem because of the overwhelming evidence amassed by scientists over decades.

Environmental art, though, is a partnership that has the potential to engineer change in people’s minds and in vulnerable natural places. For someone steeped in science, it’s also a refreshing perspective on a problem that sometimes seems insurmountable.

The exhibit at the Sesnon, “The Harrison Studio: On Mixing, Mapping and Territory,” is on display for a few more days, until March 15. Squeeze in a visit, if you can.