The deeply nasal, yet strangely calming voice would echo through my living room, keeping me company during the middle of the night. Each sentence was overstuffed with ideas, like airborne zip files, waiting to be unpacked. I would be utterly absorbed by this voice for hours, lying motionless on the couch in the dark.

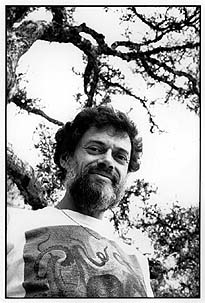

This December 21, as stories pile up about the end of the Mayan calendar, I will be thinking about the man behind that voice – ethnobotanist and psychonaut Terence McKenna – and the singularity, his prediction regarding how the world will end in 2012 as technological innovation accelerates to an infinite degree.

I will also think about how my exposure to McKenna influenced multiple aspects of my life – including my decision to become a neuroscientist.

During my college years in the mid 1990s, I devoured McKenna’s many public lectures about shamanism, psychedelics, and evolutionary theory. The best of these lectures were given at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur. Something about his hypnotic voice and his radical ideas, unlike any I’ve heard before or since, created a feeling akin to an out of body experience.

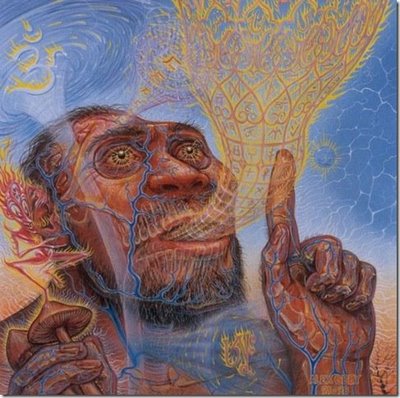

One of McKenna’s primary theories – the “Stoned Ape” theory – was that the transformation of Homo erectus to Homo sapiens was facilitated by the ingestion of the powerful psychedelic mushroom Psilocybe cubenis.

He based this theory on pieces of evidence about psychedelic mushrooms’ effects on the human brain. For example, Roland Fisher and Richard Hill of Ohio State University demonstrated that at low doses psilocybin enhances the clarity or sharpness of vision; meaning that early hunter-gatherers would have gained an advantage by ingesting the substance.

Though some of his ideas were a bit far out there – for example, he thought mushroom spores travel through space and represent alien consciousness – his work provided a launching pad for my imagination.

McKenna’s intricate analyses about the nature of consciousness – and how narrow our everyday experience is – inspired my interest in both meditation and neuroscience. My fascination with McKenna’s description of how psychedelics so easily and thoroughly alter perception (especially visual perception) actually drove me to study how the brain processes vision in graduate school.

McKenna’s concept of the singularity was also inspirational in the way I looked at technology and its role in our evolution as a species. In his first book, The Invisible Landscape, McKenna postulated that the rate of major shifts occurring in humanity’s biological and sociocultural evolution – which he collectively referred to as novelty – is constantly accelerating. He illustrated this idea with the example that the time between each major technological advance in the Computer Age is miniscule compared to the long periods of time between comparable technological advances throughout the whole of human history up to that time.

McKenna claimed the acceleration of novelty will eventually lead to a singularity event at which point anything and everything possibly imaginable will occur simultaneously, spelling the end of the world.

McKenna’s prediction for when the singularity will occur came from a computer program he wrote in the mid-1970s. The program, caled TimeWave Zero, took as inputs all of the major events in human history and plotted the occurrence of novelty throughout time. The program projected a noticeably large spike in novelty would come in December 2012.

The concept of novelty and ever-accelerating change really grabbed hold of my imagination. I began to see the world through that framework. There was evidence everywhere. The Internet was becoming a ubiquitous presence and Moore’s Law – computing capacity doubles every two years – was ensuring ridiculously cheap, near-limitless computing power. We were on the cusp of becoming masters of our genetic code. And advances in brain science and robotics were blending mind and machine.

In some weird way, McKenna’s concept of the singularity was reassuring. To me it offered hope that the end of the world would not be a random natural event like an asteroid impact or an abrupt pole-shift, or even a man-made catastrophe like a super virus or global-thermonuclear war. It felt like it could be the beginning of something rather than the end of something.

Sadly, McKenna is not around to see how his prediction panned out or to see how influential his work has become. He passed away in 2000, at the age of 53, from glioblastoma multiforme – an aggressive form of brain cancer. Twelve years after his passing, I think of him often and occasionally strap on some headphones and let that distinctive voice seep into my cortex and inspire me all over again.