I personally find it impossible to believe anything as cute as this deer mouse poops at all. Photo credit: Chris Kilonzo

Today, the Food and Drug Administration will close down the outside comment period on changes proposed to the Food Safety Modernization Act, or FSMA. Field mice could give a crap.

One of the proposed changes would establish rules to minimize the risk of crops becoming contaminated with bacteria, parasites and viruses from animal droppings. The agency is more than a little concerned that pathogen-laced poo-poo poses a serious health hazard to consumers. And with good reason.

In 2006, an E. coli outbreak in California sickened over 200 people and killed three. Health officials traced the source back to one spinach farm, but the question remains as to how it got there in the first place. While researchers proved more cattle and feral pigs within about 6 square miles of the farm were excreting the bacteria than usual, officials could not determine if their fecal matter directly contacted the crops.

Irrigation ditches in the area also harbored unsafe E. coli levels. Although this contamination was likely due to pig or cow excrement, the ditches may have delivered tainted water directly to the spinach. People could have easily stepped in some nasty and tracked it into the field. They couldn’t pin the blame on critters for their pestilent poops if humans were funneling their funk into our food.

But that’s not to say the FDA did nothing. In 2008, along with UC Davis, it established the Western Center for Food Safety to monitor the biological hazards presented by animal droppings. Now, if researchers determine that large numbers of animals are dropping pathogens, they can inform farmers.

Rob Atwill, a veterinary epidemiologist at UC Davis and a principal investigator at the WCFS, has been part of the monitoring crew since the center’s inception. In his team’s most recent study, published in October’s Applied and Environmental Microbiology, the researchers examined pathogens dropped by rodents trapped around the edges of farms in Monterey, Calif. If mice were caught in the middle of a produce field, they would be stuck there all night with nothing to do but defecate, which is why the team trapped at the edges.

Although the traps are named like instruments of death — Shermans and Tomahawks― no animals were harmed during the study. Graduate students Chris Kilonzo, first author of the study, and Eduardo Vivas live trapped the rodents and made sure they were comfortable. They put fresh bedding in each trap to ensure rodents were warm during their overnight stays. Kilonzo also told me they would rush back to farms if it started raining during the night so that they could release any trapped animals.

It’s called a kangaroo rat because you just want to cuddle it up and carry it around in your pocket all day. I mean, I think that’s why. Photo credit: Chris Kilonzo

Over a two-year period that included 8,113 trap-nights ― the number of traps set multiplied by the number of nights spent trapping ― the teamed collected 1,043 fecal samples from 13 different farms.

While only two rodents tested positive for E. coli, almost three out of every 10 came up positive for salmonella. The numbers for Cryptosporidium and Giardia parasites were closer to one in four; Atwill explained that parasites like these can ruin your day, but they won’t replicate outside of a host like bacteria do, making them much less likely to cause an outbreak.

Still, there can be thousands of mice in a nest, meaning hundreds are shedding salmonella and/or parasites. Shedding is science-speak for dropping deuces. Remember that next time somebody tells your their dog is shedding like crazy. Anyhow, even if they are just hanging out at the edge of the field, just how much of their crap can we afford to tolerate?

“When is there credible human health risk?” asked Atwill. “That’s why we’re working on this, to try and come up with some of those answers.”

This is where things get mucky. Yes, there is a definite health hazard. According to the FDA, nearly 48 million Americans contract foodborne illnesses every year. And yes, animals near farms are carrying the same pathogens that make us sick. But we can’t say for certain if or when it becomes a problem.

“What we know is that there’s a hazard,” said Mary Bianchi, a farm adviser and the county director for the UC Cooperative Extension in San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara Counties. “What we don’t know very well is what risk is associated with that.”

The difference between hazard and risk is subtle, but important. I will attempt to explain with a thinly veiled criticism of an example using Tony Romo, quarterback for the Dallas Cowboys.

Every time he throws the football, he’s presumably trying to get it to a teammate. But sometimes an opponent will catch it. That’s the hazard. If I were to tell you that an opponent only caught 2.7% of his passes, that would be the risk. Knowing that risk helps you manage a situation. If you can keep his number of throws down, you can minimize the unfavorable outcomes.

“There are some studies that are beginning to look at what kind of inferences you can draw from the presence of bacteria and foodborne pathogens,” she said. “That’s what will get us to risk management.”

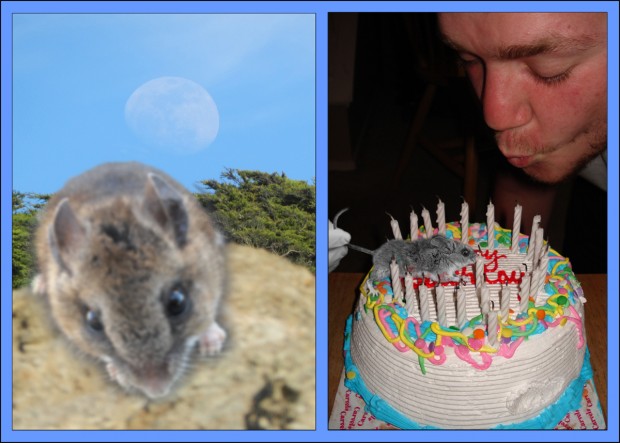

I’ve cleverly hidden a potential food safety risk in one of these photos. Can you find it? Seriously though, when it comes to wild animals and food safety, risks are hardly ever obvious. Do thousands of mice nesting in an uncultivated vegetative buffer near a farm pose a health risk? Maybe, but what are the odds and what should be done about it? That’s what produce producers, scientists, food safety experts and conservationists are all working on together. Mice pictures from Chris Kilonzo, photoshopped by Matt into photos from his own personal library.

Yet the amendment to the FSMA states that its protective guidelines are based on scientific risk assessment. While any measure that could reduce foodborne illnesses certainly has merit, this proposal seems premature. The risk assessment isn’t fully formed yet.

This may seem like a semantic snag, but the proposal calls for farmers to spend an estimated $1.6 billion. If it were me, I would want to know exactly what I was spending that money on. If the proposed measures are enacted, there will be increased monitoring of fecal specimens across the country, which is certainly a must. Scientists like Atwill have shown its value and many farmers in California are already engaged in these monitoring activities voluntarily.

But no one yet has concrete answers for how to best react if the tests show heightened levels of pathogens. Essentially, they don’t know the most effective way to keep their number of throws down.

Each farm is a unique situation. Right now, under the California Leafy Green Products Handler Marketing Agreement, farmers are urged to stop harvests to call in experts to assess their situation when fecal hazards are about. The new proposal won’t change that—it’s not fixing what isn’t broken—but it doesn’t appear to offer solid options to prevent future fecal contamination from happening. To me, it looks like the preventative step is implemented between potential contamination and distribution, not before contamination.

I’m not arguing for this proposal to be scrapped, I’m just saying give it time. Farmers, scientists and even conservationists are currently working together to establish best practices on a farm-by-farm basis.

“The conversation about balancing food safety and sustainability issues is going to be discussed more broadly within the produce industry,” said Bianchi. “And I think that that’s a great trend.”

The FDA appears to have recognized the value of these broad discussions. When the changes to the FSMA were first proposed in January, the FDA planned on closing the outside comment period in May. Now, nearly a year later, it’s still listening.