Menstrual blood may be the key to better care for people with endometriosis

Studying it could help reduce the stigma surrounding menstruation that has delayed women’s health research for decades, Gillian Dohrn reports. Illustrations by Liz Edwards and Monica Loncola.

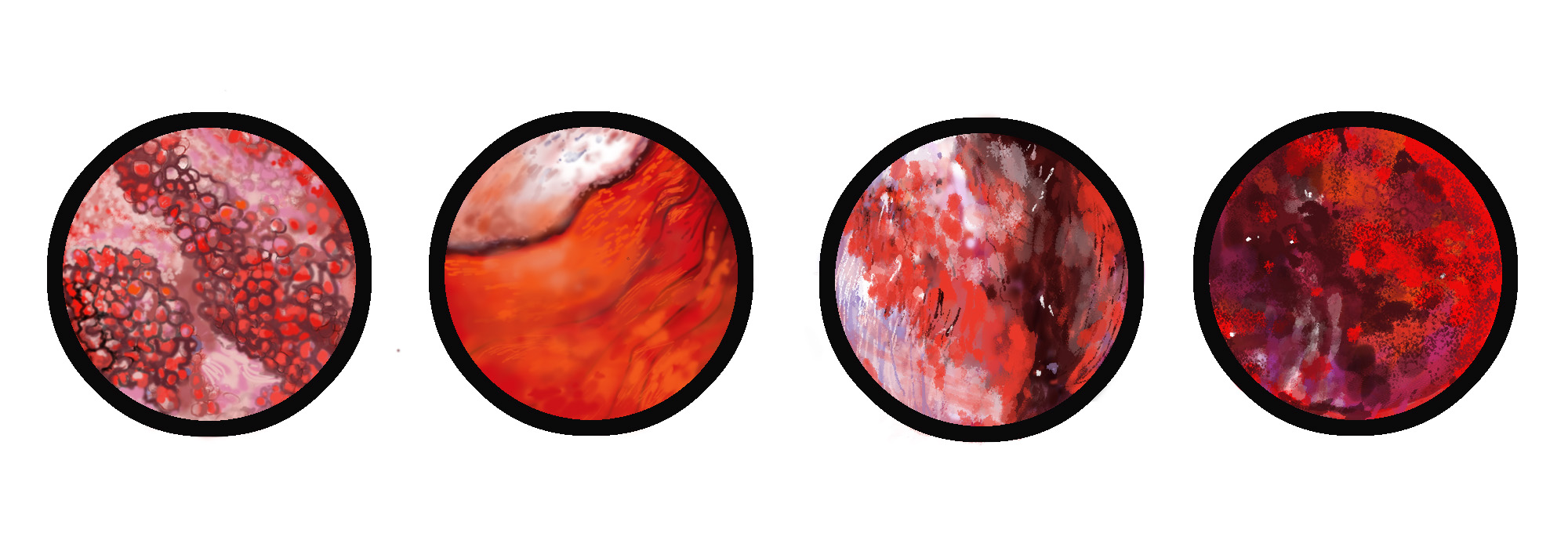

Illustration: Monica Loncola

TOn a Friday in November 2006, Annalisa Iannone awoke with a sore abdomen. Flat on her back in bed at Highland Hospital in Rochester, N.Y., she began piecing things together. The first clues came from beneath her gown, where she discovered bandages covering fresh incisions on her belly.

One long cut spanned her abdomen, just north of her pubic bone. Several smaller ones surrounded it. “I basically had a C-section scar,” Iannone said. “So… what’s up? What happened?” she asked her doctor.

She’d come in earlier that day to have a large ovarian cyst removed. Due to its location and size, the doctors couldn’t confidently predict what the operation would entail until they saw it.

They started by inserting a camera through a small hole near her belly button. After glimpsing the mass on Iannone’s left ovary, they elected to open her up—another cut, this one revealing her reproductive organs and the entirety of the mass, a grapefruit-sized endometrioma.

Endometriomas are a specific type of cyst filled with menstrual blood. They are hallmarks of advanced-stage endometriosis, a condition in which cells from a person’s uterus escape and migrate elsewhere in their body. Iannone’s surgeons carefully drained and cut the endometrioma from her ovary and abdominal wall. As they worked, it became clear that this would not be her last surgery.

With her pelvic cavity on display, Iannone’s doctors found evidence of endometriosis everywhere. Her uterus and ovaries were riddled with what clinicians call lesions and adhesions, the growths and scars resulting from endometriosis spreading undetected for years.

Iannone had long suspected that the pain she experienced with her monthly period was caused by endometriosis, but she wasn’t officially diagnosed until her 2006 surgery. Surgery is considered the ‘gold standard’ method for diagnosing endometriosis but it still takes close to seven years on average for someone to be diagnosed after their symptoms start.

Despite impacting roughly 190 million people worldwide, endometriosis is still poorly understood. There is no cure, and the barriers to getting diagnosed dissuade many from pursuing treatment entirely. It is now widely accepted that cultural stigmas surrounding frank discussions of women’s reproductive health have slowed research.

Now, scientists are working on new ways to detect endometriosis using menstrual blood. With noninvasive screening tools and diagnostic tests, doctors could approach diagnosis and treatment differently, improving prospects for people with endometriosis and offering peace of mind to the millions suffering from symptoms.

One of the researchers spearheading this effort, Christine Metz of Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in Manhasset, N.Y., has been working on developing an alternative to the surgical diagnosis for over a decade.

“It’s very clear that this gold standard is not the perfect thing,” Metz said.

Pain, period.

“I didn’t know what was going on, I didn’t know what it was,” Iannone said, “but I knew I was in excruciating pain.”

Iannone was 28 years old when she went in for surgery in 2006. She started having symptoms of endometriosis around age 15, but as a teenager in the 1990s, talking about periods was still taboo. She had no way of knowing that her painful periods were indicative of a serious health condition.

“You don’t know what a normal amount of pain is,” Iannone recalled. “It’s just such a personal thing.”

Still, she remembers the pain dropping her to her knees. It disrupted daily life and left her feeling alone and confused. She knows better now, but back then, she just did her best to suck it up. For years, Iannone put her head down and ground her teeth through cycles of debilitating pain.

She finally consulted a doctor when the pain drove her to the emergency room in college. She now speculates it was a cyst rupturing but the doctors were dismissive. They sent her home with Tylenol after ruling out appendicitis and a urinary tract infection. She was 18 at the time, away at school and scared.

“I didn’t know what was going on, I didn’t know what it was,” Iannone said, “but I knew I was in excruciating pain.”

Iannone learned to cope with pain. Its cyclical ebbs and flows became part of her routine. Being an extrovert, she leaned on her friends. As an undergraduate student at the University of Rochester, she found her “band of ladies.” She took some solace in shared discomfort.

“Periods suck. Even when they’re not that bad. Periods suck,” Iannone said.

When Iannone saw a gynecologist for the first time in her mid-twenties, they prescribed her birth control to help manage her period symptoms, making no mention of endometriosis. Doctors frequently prescribe birth control to alleviate period pain, but for Iannone, it only made things worse.

Cursory examinations from doctors in the years following revealed little more than she already knew – likely endometriosis, definitely painful.

Life went on like that for a few years before her symptoms became impossible to ignore. The endometrioma growing on her left ovary was visibly deforming the smooth curve of her stomach. Her partner, now wife, urged her to see a doctor.

An endometrioma of that size is one of the few criteria allowing doctors to confidently predict endometriosis without surgery, but they still had to operate to remove it. This is not uncommon. Doctors often confirm a suspected diagnosis during an operation scheduled to treat the symptoms of endometriosis.

When Iannone went in for surgery in 2006, her endometriosis was already widespread. The errant cells had run rampant, fusing her uterus and reproductive organs into a sticky column of tissue and invading her bladder and bowel.

This kind of tissue growth not only makes periods painful but also causes abnormal bleeding for many people and can make using the bathroom and having sex very uncomfortable as well.

“Would it have been different? If they had caught it earlier?” Iannone said. “I guess I always wonder.”

Cellular deviants

Although there are several theories on the origins of endometriosis, the most widely accepted comes from a physician called John Sampson back in the 1920s. Everyone who menstruates experiences some “retrograde mensuration,” where blood flows in the wrong direction during a period, back into a person’s uterus instead of out their vagina.

Sampson postulated that some people develop endometriosis when some of the cells in menstrual blood take root outside the uterus and grow. Although Sampson’s theory has stood the test of time, it is still not clear why retrograde menstruation results in endometriosis in only approximately 10% of people who menstruate.

Because period “blood” is a mix of blood, tissue cells, hormones, and other biological matter, this rich mixture is ripe with health data. It contains discarded uterine cells, the same ones that line the uterus for pregnancy. They’re very adaptable, which also enables them to grow in other parts of the body.

For people who develop endometriosis, cells can slowly infiltrate other organs, sometimes even spreading to other regions of the body. Doctors have observed endometrial in places as foreign as an eyeball. Although it is mostly common in women of reproductive age, endometriosis can also impact transgender men and nonbinary people.

Metz, who studies women’s health at Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, says endometriosis is difficult to detect because cells grow “like an iceberg, not a wart” when they invade surrounding tissue. Instead of protruding, they often infiltrate.

Endometrial cells respond to the signals a woman’s body produces during reproductive cycles no matter where they are growing. The endometrium thickens to prepare for egg implantation. If there is no fertilized egg, the excess lining is shed as a period.

In other words, small clusters of endometrial cells growing on someone’s bladder or bowels can become inflamed and bleed each month, just like uterine cells, causing scarring that can compromise organ function over time.

Sometimes, trapped menstrual blood forms cysts, like Iannone’s endometrioma.

Taken together, this complicated condition is often excruciating and can impact almost any other biological function, including fertility. Most people find some relief through surgery, but lesions often grow back after removal.

Because of how endometrial lesions grow, capturing them with medical imaging is difficult. Ultrasound and MRI technology are improving, expanding the realm of possibility, but surgery remains the only way to discern endometrial tissue from other tissue.

“We’re stuck with the surgical procedure,” Metz said.

The gold standard doesn’t glitter

Jeanette Lager, a gynecologist at the University of California, San Francisco, works in a dedicated Endometriosis Center alongside a team of specialists offering comprehensive care. By the time patients get to Lager’s office, most have seen several other doctors and tried upward of five different strategies for managing their symptoms, including surgery.

Lager cites the delay to diagnosis as a major hurdle for patients. These diagnostic limitations also impact the development of less invasive treatment strategies. Most studies require participants to have a confirmed diagnosis to validate the results, which limits who can enroll in the study.

In other words, more people need to get diagnostic surgeries so that scientists can develop alternatives to surgery. For people with endometriosis, the consequences of the delay can be physical and psychological, Lager said.

“They can feel discounted,” Lager said, “like their pain is not real.” Over time, this normalizes a level of discomfort meant to indicate that something is wrong. Iannone’s experience is just one example of what can happen without intervention.

Endometriosis impacts roughly one in nine people who menstruate (including transgender men and non-binary people.) Given that many people either choose not to or can’t get surgery because it is invasive, expensive and risky, this number is likely even higher. Roughly half of the world’s population will spend 3,500 days menstruating during their lifetimes. The collective burden of this condition is enormous.

Still, endometriosis has just begun to capture public attention in the United States in the past few years. Outspoken celebrity advocates and dedicated scientists spurred a movement to raise awareness and drive new research. In November 2023, President Biden announced the first-ever White House Initiative on Women’s Health Research, led by First Lady Dr. Jill Biden.

Researchers rely on government funding and grants to study endometriosis and doctors rely on research to treat patients. Thus far, clinicals have focused on managing the symptoms of endometriosis. No one has figured out how to see it early enough to stop it from spreading.

Metz thinks menstrual blood can change that. She’s been studying endometriosis for over a decade in a study based at Northwell Health’s Feinstein Research Institutes in New York. They’ve collected and analyzed thousands of menstrual blood samples from study participants across the United States in an effort to develop non-invasive screening and diagnostic tests.

In September 2022, Metz and colleagues published their results in a research paper describing the differences between the menstrual blood of people with endometriosis and healthy individuals. Now, they’re preparing to propose a new test to the FDA that will be able to identify these differences in a menstrual blood sample.

Getting people to accept the clinical value of menstrual blood is another challenge. Back when Metz and co-director Peter Gregerson launched the Research OutSmarts Endometriosis (ROSE) study in 2014, they encountered a lot of skepticism.

“A lot of physicians would tell us, ‘Oh, I can’t possibly get my patients to give menstrual blood’,” Metz recalled. That turned out to be false. The team began advertising the ROSE study on social media sites and found many people were eager to participate.

But, before they could begin processing samples, the researchers had to figure out how to collect and transport samples, and they quickly learned that no one had ever collected menstrual blood for research in the United States before. “There were no protocols,” Metz said, “no standard operating procedures.”

The rise of ROSE

Eventually, Metz and Gregerson developed an at-home collection kit that provided participants with the tools they needed to collect and return menstrual blood samples. Participation expanded even further during the COVID pandemic when people were stuck at home, and telemedicine replaced many standard office visits, normalizing practices such as remote sampling. They’ve now received samples from thousands of people across America, both and healthy and with endometriosis.

Metz compares it to giving a fecal sample if you have inflammatory bowel or celiac disease. “I’ve never heard anyone say, ‘I’m not doing that.”

A recent study in France underscores this point. Scientists surveyed healthy women and women with endometriosis to find out whether they were willing to give a menstrual blood sample. 78% responded that they would.

As far as Metz is concerned, 78% is not good enough. She thinks the stigma surrounding menstruation has caused researchers to overlook the potential value of period blood, often citing the ‘yuck factor’ as a barrier.

As of fall 2024, The ROSE study is enrolling participants for phase two of a clinical trial designed to validate the initial findings. If they can demonstrate that the blood-based method matches the results of diagnostic surgery, they will be one step closer to unseating the gold standard.

Their vision for the screening test mirrors a protocol used to test for birth defects during pregnancy. First, a routine blood test. If the results come back abnormal, doctors can follow up with more targeted tests, like an amniocentesis, which involves extracting fluid from the womb with a long needle. The secondary tests come at a higher cost – they’re riskier and more expensive – and they offer much more information.

A blood-based screening test for endometriosis won’t replace surgery, but it could ease the burden for women. By distinguishing a pathogenic period from a painful one, doctors might be able to prevent years of inexplicable suffering and scarring. Having more information opens the door to new treatment options and opportunities for data collection.

With more and more scientists studying endometriosis and other conditions termed “women’s health issues,” attitudes are shifting both inside and outside the laboratory.

“If you look at the number of [research] papers that use the words menstrual blood or menstrual effluent, it has increased dramatically,” Metz said. “Believe me, when we did it, they thought we were nuts.”

Relatively speaking, scientists have only just started studying women’s bodies. Until 1993, pregnant women and women of childbearing age were excluded from clinical trials due to concerns about their reproductive health. Although legitimate, these precautions created deep holes in the scientific literature on issues unique to female biology.

At approximately the same time that Iannone’s endometriosis saga began in the 1990s, the US government flipped its ruling, recommending that women be included in clinical trials. A lot has changed since then, but filling in the gaps takes time.

“Eventually, science has to catch up,” Iannone said, who shares her story with the hope that it will spur change.

“Nobody is ever going to know about [endometriosis] if we don’t talk about it,” Iannone said, who shares her story now with the hope that it will spur change, “Eventually, science has to catch up.”

© 2024 Gillian Dohrn / UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

Gillian Dohrn

Author

B.A. (molecular and cellular biology) Colorado College

Internships: Stanford News, Monterey Herald, Nature

I’d all but forgotten about Girl Speaks of Toes when I encountered my middle school science teacher at a baseball game last summer. The poem describes how I made peace with my unconventional feet as a teenager. It’s weird and whimsical, with a nod to genetics that was lost on me at the time. He excitedly reported that he’s still using it as an example for the 6th grade poetry unit nearly fifteen years later.

Although the toes in the poem are mine, my sister, mother, and presumably others share their shape. This sense of kinship ultimately allowed me to appreciate my weird feet. As a science writer, I’m eager to explore the nuances of relatedness. I aspire to tell stories that inform, entertain and invite the reader to explore what it means to be human.

Liz Edwards

Illustrator

B.S. (Cognitive Neuroscience, chemistry and psychology minor) University of Denver

Internship: Monterey Bay Aquarium

I grew up roaming the forests of Oregon where I learned to commune with the trees. When I moved to Colorado for college, I fell in love with the mountains and the flourishing ecosystems that accompany them. In my most recent adventures to California, where I moved to study Science Illustration at CSUMB, I have found an additional admiration for the ocean. In college, I studied anatomy and cognitive neuroscience. After graduation I worked at Denver Botanic Gardens School of Botanical Art & Illustration. Through all of these varying experiences and adventures, two things have remained constant: my connection with nature and a deep understanding that this world will never stop offering things to learn about. Through my illustrations, I hope to promote accessibility and inclusivity that allows others to connect to these same feelings and reminds us all that science and nature are things everyone can, and should, engage in.

Monica Loncola

Illustrator

B.F.A (studio arts) Rosemont College

Internship: Western Flyer Foundation.org

I'm fascinated with the biodiversity of the natural world. As a child I spent my summers at the ocean’s edge collecting shells, bones and artifacts of nature. I drew intuitively and studied art formally at the university level. I’ve kept journals my entire life documenting my travels and experiences through drawings and annotations. I'm especially passionate about how nature survives cycles of life and death in harmony, destruction and interdependence. Whenever I look into a microscope, I see the potential for a detailed illustration and an abstract painting simultaneously. Science Illustration is the perfect marriage of the two disciplines. My intention is to bring to the viewer through my unique perspective, knowledge of the world around us through accurate depictions of a situation or process. Combining science and art is the perfect platform to move forward with my passion to educate and convey how life forms, sustains, and decays all in keeping a profound balance for the sustainability of our planet.