Restoring the Caribbean’s natural defenses with federal funds

An unprecedented designation opens up federal aid for coral reef restoration. Reported by Molly Herring. Illustrations by Evelyn Lam and Brynna Reilly.

Illustration: Evelyn Lam

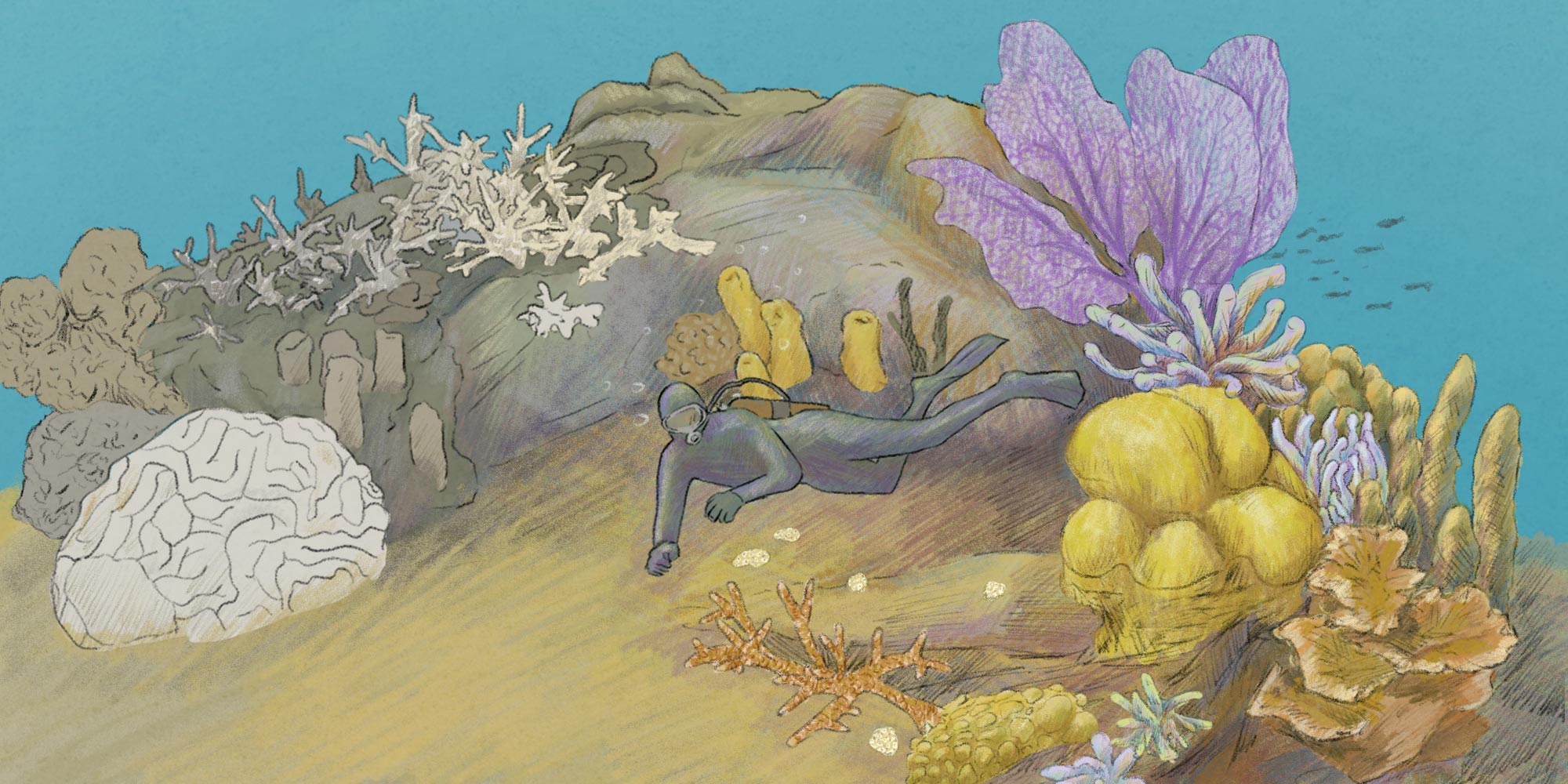

Under the blue lights of the bubbling coral nursery, he points out grooved brains with bright, tunneling mazes and waving pillars with pink, jelly tentacles. These young corals are safe and healthy, basking in the warm glory of ultraviolet light and daily attention.

Soler is a coral farmer at The Nature Conservancy’s Caribbean outpost, a retired sugar plantation turned open-air office building on St. Croix, in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Every morning, he and his team of aquaculture specialists pamper their resident corals with health checks, antibiotic baths and microscope inspections. “Our job is to maintain the health of an entire miniature ecosystem,” said Soler. “So long as the ecosystem within that glass box is cared for, the coral will never die.”

Although delicate individually, in the expanse of a reef, healthy corals together act as a formidable shield, protecting shorelines from storm surges and violent wave action. But rapidly warming water temperatures and increased ocean acidification — both due to human-caused climate change — are weakening much of the world’s tropical coral reefs while simultaneously strengthening the severity and frequency of tropical storms and hurricanes, especially in the warm, shallow Caribbean. Efforts to restore disappearing reefs with lab-grown corals are met with varying success as transplantation can stress the corals, and storms, disease or heat can wipe out newly planted corals before they’re established.

Two such storms carved through the Caribbean in September 2017. Hurricanes Irma and Maria, both Category 5 hurricanes, swept through in quick succession, not two weeks between them. The pair ravaged the U.S. Virgin Islands, killing over 3,000 people across the Caribbean and southwestern United States. The storms also destroyed the in-water coral restoration project off the coast of St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands.

After the catastrophic hurricanes in 2017, and faced with the likelihood of similar or greater magnitude storms in the near future, the federal government is officially recognizing the protective power of healthy coral reefs. In October 2023, a group of government agencies called the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force passed a policy resolution categorizing coral reefs as “natural infrastructure.” This simple designation creates a pathway for federal disaster relief money to conserve coral reefs – money the conservation field could previously only dream of.

“Coral restoration is a super difficult problem if you’ve only got tens of thousands of dollars. This federal money will be a game changer,” said Mike Beck, director of the University of California, Santa Cruz Center for Coastal Climate Resilience, whose research helped demonstrate the economic value of coral reefs.

Conservationists are hopeful this new federal designation and substantial source of funding will help communities and researchers prioritize coral reef restoration for risk reduction in the face of climate change.

A peek inside a polyp

Coral reefs are simultaneously plant, animal and rock. To build a reef, a tiny jellyfish-like animal called a polyp floats around until it lands on a hard surface like a rock or other reef. Then, the polyp sucks dissolved carbon dioxide from the surrounding ocean water and turns it into a limestone skeleton of brain-like mazes or spindly branches. Bits of algae float by, bunk up with the corals, and photosynthesize, spinning sugar from sunshine to feed the coral polyps, which in turn, provide protection with their microscopic stingers and rigid skeletal home.

A healthy coral reef is made up of millions of polyps. This mini-metropolis provides essential habitat for tropical fish, offers a gathering ground for subsistence fishermen, and attracts scuba diving tourists with money to spend. Coral reefs are also the shoreline’s first line of defense. Their limestone fingers, tunnels and pockets act like speed bumps for the ocean’s energy. Healthy reefs trip incoming waves, causing them to curl, crash and dissipate before they reach the beach. They can even adapt to the swell, growing in response to wave direction and strength.

Since the 1950s, half of all healthy coral reefs have perished. Scientists mainly attribute their demise to the human-caused excess of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, which acidifies ocean water and traps heat. When the water becomes too warm, the photosynthetic algae that feed the coral polyps start producing toxic compounds, forcing the coral to expel the algae. If the algae is absent for too long, the coral polyps starve. Excess acid in the water weakens the coral skeletons and slows down their growth. Coupled with stronger, more frequent storms, “the reefs are having a hard time catching up to the rapid changes around them,” said Kelcie Troutman, St. Croix resident and the education and outreach coordinator at St. Croix East End Marine Park, a marine protected area that surrounds the island’s east side.

If the planet continues to warm at its current pace, scientists predict 70% to 90% of the remaining corals will be lost to the continued effects of climate change, as well as pollution, stronger storms and unsustainable coastal development.

A steady uphill climb

Even with the odds stacked against them, coral conservationists in the Caribbean haven’t given up. Ecologists are continuously adapting their methods of removing and rehabilitating stressed corals so they can be replanted in the wild and have another chance at survival and reproduction. To grow hardy, reef-building species like boulder and staghorn, Caribbean coral research groups use coral nurseries — some land-based, like the saltwater tanks at TNC, and some situated in relatively calm nearshore waters. Corals that successfully grow in nurseries are then planted onto wild reefs, where they hopefully survive, grow and reproduce enough to support fish, feed humans, and protect coastlines.

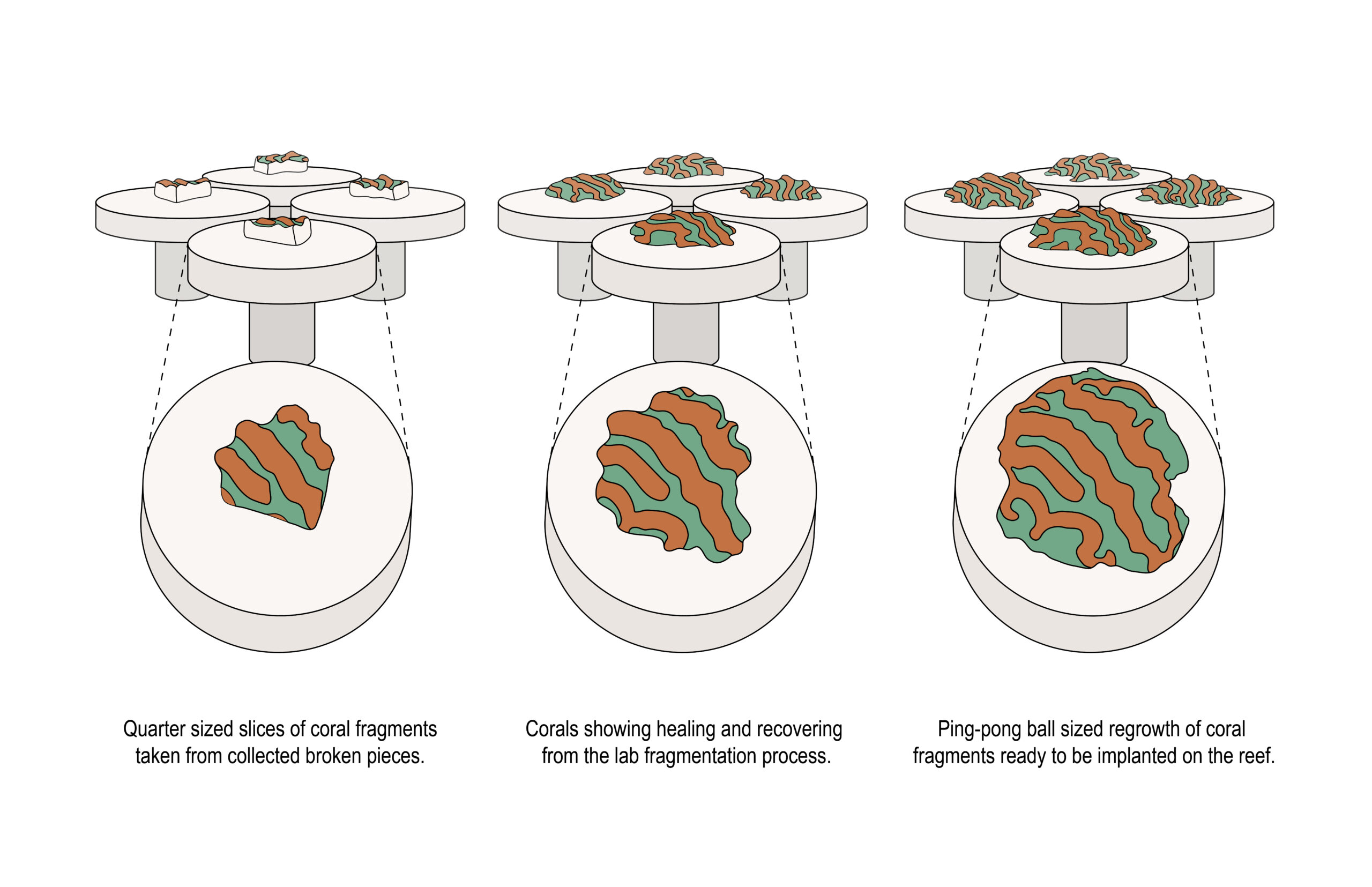

At the Nature Conservancy’s outpost on St. Croix, the land-based coral nurseries look like hot tubs on stilts. Soler, who has been growing corals for 12 years, propagates boulder coral from broken fragments collected by TNC scuba divers.

Illustration: Brynna Reilly

Once rescued, the damaged corals first acclimate to the TNC nursery. Soler and his team inspect them for diseases or predation, pump the tanks with clean water, and help the corals recover from the high-stress ocean environment. After about a month, Soler slices them into quarter-sized bits with a diamond-encrusted jewelry saw. The cutting initiates a wound-healing response for faster growth. After the coral edges have healed and grown to about the size of a ping-pong ball, divers carry them to nearby wild reefs and attach the healthy fragments to the reef with clips, glue or plugs. Then they cross their fingers.

TNC Caribbeans’ whole operation, including outreach and education staff, costs $1.1-1.3 million per year, most of which comes from NOAA, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, and the National Park Service. Their primary coral conservation project is restoring around 50 acres of reef within the East End Marine Park and Buck Island Reef National Monument. In 2022, the TNC team planted 5,455 lab-grown corals. They also used sexual reproduction to help an estimated 14,000 new coral larvae settle in the wild, increasing genetic diversity and resilience in the local reef populations. They have yet to assess the survival of these corals.

Corals are picky. Some species refuse to grow in the land-based bubble baths and instead prefer the consistent currents of the open ocean. On the island of St. Thomas, home to the University of the Virgin Islands, ecologist Marilyn Brandt tends an underwater coral nursery. Her team primarily raises a fast-growing species called staghorn coral. A few meters deep, the nursery looks like an eerie, PVC pipe forest. Fragments of the finger-like staghorns dangle like Christmas tree ornaments from the plastic branches. The coral polyps catch and eat tiny creatures called amphipods in their microscopic stingers.

Unlike land-based nurseries, their underwater counterparts are immediately vulnerable to declining environmental conditions and severe storms. Hurricanes Irma and Maria damaged the U.S. Virgin Islands’s mature reefs and wiped away Brandt’s underwater nurseries, which were too young and brittle to survive the beating. By the time the University of the Virgin Islands’s team made it out on the boat to check on their nursery, “it looked like a bomb had gone off,” said Brandt. The researchers cleaned up the carnage and started over.

Coral restoration is a Sisyphean effort. With every degree of temperature rise and increase in acidity, the boulder rolls back down the hill, and ecologists dutifully follow.

Some Caribbean coral restoration projects, such as Coral Vita, are experimenting with ways to help nursery-reared coral adapt to the poor water conditions in the wild more quickly, hopefully increasing corals’ chances of survival. Using a method called coral conditioning, aquaculture specialists remove stressed corals from a reef and plop them into a spa with perfect conditions. The general idea is that once the mother coral has adjusted to the conditions in tank one, an ecologist slices off a piece and rehomes it in tank two, which has slightly poorer water quality. Gradually, pieces of the coral are moved from tank to tank, each slightly warmer, more acidic, and closer to ocean conditions. Scuba divers then plant the acclimated corals onto a wild reef, where they just might have a better shot at survival. After using coral conditioning, Coral Vita reports their survivorship rates are between 45% and 99%.

Coral restoration is still a relatively new and rapidly evolving science. There is vast potential for improving restoration methods and technologies, but conservation efforts are restricted by a lack of funding. Access to federal disaster relief funding creates a new financial pipeline for coral restoration that will be a game-changer for the field. “Coral reef restoration has been primarily funded by research funding, private donations, and conservation money,” said Brandt. “So by recognizing it as natural infrastructure, you have access to funding that is usually reserved for built infrastructure. That tends to be a lot bigger of a pot of money.”

New money leads to new solution

In the event of any natural disaster, federal organizations like the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the Army Corps of Engineers deploy specific pots of funds to states, tribes and territories to help them recover, rebuild and guard against future disasters.

“If you sum up all conservation money globally, it’s in the single-digit billions of dollars. If you sum up disaster recovery and mitigation, it’s in the hundreds of billions, even trillions of dollars in scale each year,” said Beck. But these federal funds have historically only covered repairs to human-built infrastructure, excluding the restoration of natural systems.

The goal of any FEMA hazard mitigation project is to reduce risk to people and property. “As long as the project meets this requirement and the other eligibility criteria for the applicable hazard mitigation grant program, there is a lot of flexibility in how funding is allocated,” said Janan Reilly, the acting branch chief for community infrastructure resilience at FEMA headquarters in Washington D.C.

A frequent challenge for nature-based solution projects getting access to this funding is that they must preemptively demonstrate their cost-effectiveness. It’s more difficult to identify the future benefits of nature-based projects that are newer and more innovative. But after the double hurricanes carved through the Caribbean, federal officials realized the need for diversified shoreline protection. A FEMA representative suggested to Beck and his colleagues that it would be helpful to have a thorough cost-benefit analysis of coral reef restoration as a nature-based solution to storm damage.

To quantify how well reefs protect shorelines, Beck and his collaborators, which included experts from the U.S. Geological Survey and NOAA created computer wave models, which estimated the benefits that healthy coral reefs provide in attenuating wave energy and thus reducing flood damages. They estimated that, in the U.S., healthy reefs provide more than $5 billion in storm protection benefits annually; part of the $172 billion that US reefs are projected to provide through many ecosystem services including tourism and fisheries in addition to coastal protection.

Together with other team members from USACE and FEMA compiled their findings into a report and guide, titled Coral Reef Restoration for Risk Reduction (CR4): A Guide to Project Design and Proposal Development. The freely available document not only summarizes the overall costs and benefits of U.S. coral reef restoration projects, but also details the novel practices researchers can apply to quantify the benefits of specific coral reefs. The document also lists sources of federal hazard mitigation funding that are potentially available for reef restoration and other nature-based projects. Given coral’s protective benefits, the authors of the guide proposed that coral reefs are just as valuable, if not more valuable, than human-made infrastructure, and recommended agencies categorize healthy reefs as “natural infrastructure.”

“We are going to be spending this money, and it’s either going to be used to build more gray infrastructure that further destroys nature, or we could turn it into a positive for restoration of natural infrastructure and provide a far more massive pile of funding than would ever have been possible through conservation funding,” said Beck.

In July 2023, Puerto Rico put the guide to the test, using it to help secure $38.6 million from FEMA for the San Juan Reef Restoration Project off of San Juan Bay. “This is the first use of hazard mitigation funds for coral reef restoration,” said Curt Storlazzi, a coastal scientist at USGS and coauthor of the CR4 guide.

Three months after Puerto Rico received this funding, the Governor of the Virgin Islands released an executive order declaring coral reefs as natural infrastructure. In October, the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force followed suit, passing a policy resolution granting infrastructure status to coral reefs along the entire U.S. coastline. This means future proposals for government funding to support reef restoration as hazard mitigation projects no longer need to outline the cost-benefit of coral reefs. “This is not a question anymore. We don’t have to convince people that corals function as infrastructure,” said Reilly.

Now, states, territories and tribes can apply for FEMA hazard mitigation and recovery grants, and use that money for the restoration of coral reefs and, theoretically, other ecosystems that align with FEMA’s goals of protecting infrastructure and people. “We are creating the funding mechanism to better protect coastal communities, make them more resilient to climate change, and increase the fisheries, tourism and biodiversity that those of us who love coral reefs really care about,” said Storlazzi.

They can incorporate nature-based solutions to address hazard mitigation problems. Funding efforts such as the development of coral nurseries is possible if there is a clear connection to risk reduction, like growing corals to build out a reef as part of the project and supplying the materials needed for the risk reduction design, said Reilly.

With nearly a quarter of the island’s population living below poverty, coral reefs may not be top of mind for most Virgin Islanders, but these new federal funding sources could create momentum for new jobs in reef restoration by promoting investment in training the next generation of local aquaculture specialists. Conservationists such as Brandt, and others, hope that additional funds will encourage and allow more local residents to become involved in reef restoration. “The most important thing for people to know is that the coral reefs are protecting their home and their shoreline, and their shoreline is part of their home,” said Troutman, the East End Marine Park education and outreach coordinator.

Delicate prospects

Plans for Puerto Rico’s FEMA-funded reef restoration include an artificial component tailored to the San Juan reef. This hybrid reef will likely consist of a cement base with plenty of pockets for baby coral polyps to plant and grow. Because of its physical structure, a hybrid reef can provide immediate protection for island communities, and at the same time, offer a launching pad for coral growth. Ideally, the out-planted corals overtake the structure, spilling over the edges and building a robust and healthy reef.

The Department of Defense has also put faith in hybrid coral reefs. The DARPA Reefense project is an ongoing effort to develop quick-healing hybrid reefs to protect DOD infrastructure from storm damage, erosion and flooding in Hawaii and Florida.

Hybrid reefs are explicitly engineered to provide both coastal protection and conservation benefits. “With hybrid reefs, you can guarantee some protection, and buy some time to get corals on top of that. Is it going to look like a perfect coral reef restoration project? No. Could it look like a pretty interesting reef? Yeah,” said Beck.

Hybrid reefs also serve as a middle ground for ecologists who, in an ideal world, would work to no end to replant a fully natural coral reef, and ecologists who view coral restoration as a waste of resources if the goal is coastal protection.

“Right now we are acting like corals are the star and they’re not,” said Hilary Lohmann, coastal resilience coordinator at the Department of Planning and Natural Resources in the U.S. Virgin Islands. “They aren’t resilient. If corals were resilient, then they wouldn’t be in the IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] report next to glaciers.”

If conservationists’ primary goal is to restore Caribbean reefs to their prime and provide diverse habitat for fish and scuba divers, the future looks grim. Experts haven’t considered Caribbean reefs to be “healthy” since the 1970s. “I don’t think that restoring coral reefs to their original levels is possible based on how we’re doing things,” said Brandt.

But if the goal is to protect coastlines from flooding and erosion, there needs to be a wave-breaking structure in the water. Hybrid reefs fill that need while giving corals a shot at survival, but they also pose their own challenges. For example, the“green” part of hybrid reefs–healthy baby corals–makes them harder to build because engineers can’t control or even count on coral growth.

To ecologists who have been in the field for decades, some of these concerns are familiar.

In the early 2000s, oyster reefs were struggling. Similar resistance arose against the use of artificial materials for restoration, but eventually, the situation became so dire that ecologists, engineers and oyster fishermen reached a turning point. Since then, the Chesapeake Bay Restoration Project has restored over 925 football fields worth of oyster reef. Even still, only 1-2% of the historic population remains, and restoration efforts are ongoing.

“We resisted all sorts of innovative approaches until the whole ecosystem collapsed and then we were willing to do anything,” said Beck. “Trying to recreate an oyster ecosystem in the Chesapeake Bay with 1-2% of genetic diversity left was super hard and expensive. That’s what we are up against with Caribbean corals.”

Despite skepticism, local hybrid oyster reef restoration projects were successful and grew to miles long. Hundreds of community members in Maryland and Virginia grew oysters alongside their docks and then helped the Chesapeake Bay Foundation plant them on sanctuary reefs. Eventually, those projects gained federal support through economic recovery funding. The original artificial structures bloomed with healthy oysters. “Most of those reefs have been successful to the point that now, no one cares what’s underneath them,” said Beck

Without intervention, the future of Caribbean coral looks bleak. But given the choice between a cement seawall and a similar structure with even the slightest potential to become a biological habitat for hundreds of species, Beck, Brandt, Soler and many others will choose the second. Most are not ready to throw the polyp out with the seawater and rely solely on “gray” infrastructure for coastal protection, even if that means the “green” becomes secondary.

Roll the boulder back up again

Back at TNC Caribbean, Soler basks in the beauty of his coral babies. He points out which polyps are picky, which prefer light, and which thrive on the left side of the tank, for whatever reason. “Corals definitely have personalities,” he laughed.

Threats to coral reefs may seem relentless. Restoration is an expensive, tedious, uphill battle, but most conservationists are not ready to give up. Coral reefs are vital hotspots for fish and, subsequently, fishermen. They are fountains of fascination and cultural value. They protect coastal communities from worsening storms, flooding and erosion. But they are also important because they are alive, and for coral conservationists, that’s enough reason to follow the boulder back to the bottom again and again.

For now, Soler and his colleagues continue their work to restore one reef at a time, fragment by fragment. “It’s better than doing nothing,” he said. “I think that’s how everyone sees it. If we have something we can do, we might as well do it.”

© 2024 Molly Herring / UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

Molly Herring

Author

Internships: Eos, the Monterey Herald, Mongabay, Science, and Quanta

Born in a water bug family of swimmers and scuba divers, I was raised between the rolling Blue Ridge Mountains and the Outer Banks dunes. I learned my history as Appalachian folklore passed down through saltwater stories and my grandma’s sourdough.

At UNC, I assisted research on sea turtle navigation. Then I caught the travel bug. In Ghana, a Priestess of Mami Wata spotted my shell anklet and whisked me into a shrine to the mermaid spirit. In Ecuador, a Galapagueño fisherman took me diving beneath hammerhead sharks. And on the Aegean coast, a Greek baker sent me to release octopuses from algae–encrusted traps. In each place, I learned how cultural knowledge inspires ocean protection as successfully as academic research. I hope to draw from stories and science to write of those who dive into the sea.

Evelyn Lam

Illustrator

Evelyn is a science illustrator interested in communicating love for niche and beautiful with precision and care. Born and raised in Hong Kong, she graduated from the School of Visual Arts, NY, in 2023 and decided to further pursue her true love for science communication at CSUMB. Through her practice, she hopes to be able to work with people of all backgrounds to share this appreciation for art and nature.

Brynna Reilly

Illustrator

B.A. (Environmental Studies, Concentration in Environmental Education and Community Outreach) California State University Monterey Bay

Illustrator Brynna Reilly has always been intrigued by the natural world and growing up in the Monterey Bay area allowed her to have many fantastic experiences in nature. She began seriously pursuing art in college and the classes she was able to take allowed her access to expand her knowledge, skills, and passion for art. Brynna Reilly began exploring scientific illustration at the end of her undergrad experience at CSUMB. Her undergraduate work allowed her to pursue the unique field of environmental studies. Through the wonderful projects in her major studies program she was able to forge connections between environmental education and the many applications of scientific illustration. Through her time in the Science Illustration program, she learned many skills that will help her to advance her career in the field of science illustration. Through her work Brynna hopes to reveal the beauty in nature and its detailed processes that often may go unnoticed in the world around us.

@brynna_illustrates