The Right to Water: An Unkept Promise

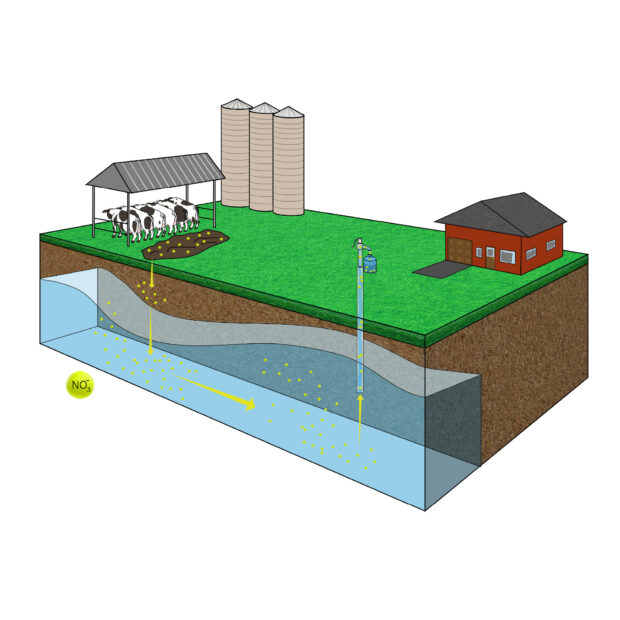

Nitrates from large animal farms can seep into groundwater and harm communities residing nearby. Researchers have found that a program to reduce nitrates is failing to provide bottled water to residents at great risk of contamination, Andrea Tamayo reports. Illustrations by Tessa Wells and Maggie Gleason.

Tessa Wells

Every few weeks, Maria Gonzales and her husband embark on a trip for clean water. They load their truck with seven empty five-gallon water containers and drive down the road to a windmill-shaped water refill station at the corner of their neighborhood. She fills up the containers, while her husband carries them to and from the truck. The five-gallon containers are heavy. Each filling costs $1.75. Since moving to California nine years ago, they’ve had to collect their own water, because they’re afraid to drink what comes out of their tap.

Maria’s home sits in an unincorporated part of Stanislaus County, in California’s Central Valley. Many of these communities are poor and lack basic public services like sidewalks, streetlights, and clean drinking water. People often rely on domestic wells, which pump unregulated groundwater that is more vulnerable to contamination.

In the Central Valley, nitrate is the most widespread groundwater pollutant. In 2021, California Water Boards estimated that 100,000 Central Valley residents are impacted by nitrate groundwater contamination. Despite being unsafe to drink, many residents in unincorporated communities are unaware of just how much nitrate is in their wells, which disproportionately saddles them with the health risks of drinking nitrate-polluted water.

In response to state regulations, a new program in the Central Valley aims to provide well-testing services and access to clean water for residents impacted by nitrate pollution. But a group of concerned researchers and community members say the program’s well-testing and water bottle delivery efforts aren’t reaching enough homes, especially those of low-income and Latino communities. Now, the researchers are conducting surveys and mapping nitrate pollution to marshal as much data as possible to ensure that the program and state make good on its promise of clean water for all people.

Too much of a good thing

When nitrogen seeps into the soil, bacteria kick off a series of chemical transformations, converting it to nitrate. Plants need nitrates to grow. But too much nitrate can be toxic to plants, animals, and people.

In 1945, Hunter Comly, a physician in Iowa, treated two infants. They had been born healthy. But after a few weeks, they had started vomiting, crying excessively, and most notably, had turned blue.

Comly recognized that both infants’ feeding formulas had been prepared with well water. When one of the infants’ fathers demanded to know what “poison” was in his well, testing revealed high levels of nitrates, which are odorless and invisible to the naked eye. Comly warned the parents of both infants to avoid using their well-water for formula, and instead use milk. At a follow-up weeks later, the babies were healthy again.

The condition Comly saw is called infant methemoglobinemia and is commonly referred to as “blue baby syndrome”. It occurs when a person drinks nitrates, which are absorbed into the blood and converted to nitrites. These nitrites can then form cancer-causing compounds and methemoglobin, a chemical that hinders the blood’s ability to carry oxygen to cells and tissues. Blood with decreased oxygen turns blue or purple, which can cause babies with nitrate poisoning to appear blue.

A 1951 U.S. survey later tallied 278 cases of blue baby syndrome and 39 infant deaths due to water contaminated with nitrates above 10 milligrams per liter (mg/L) –– which is equivalent to less than one-tenth a grain of salt in a water bottle. Based on these findings, the Environmental Protection Agency made 10 mg/L the maximum contaminant level (MCL) –– the legal threshold limit on the amount of nitrates allowed in public water systems.

Since 2000, there haven’t been any reported cases of blue baby syndrome in the U.S., according to epidemiologist Mary Ward of the National Institute of Health, in a presentation she gave in 2022.

But since doctors like Comly saw the first cases of blue baby syndrome, several studies, including Ward’s, have linked nitrate-contaminated water with other serious health issues. In a 2018 review paper, Ward found that among 21 studies that looked for connections between nitrates in drinking water and cancer, 12 showed that as people who drank water contaminated with more nitrates, they were more likely to develop cancer.

Ward has also led several of her own studies, including one in 2010 where her team found that women drinking water contaminated with nitrates had a higher prevalence of thyroid cancer. She found that those who drank water with nitrate levels above or equal to 5 mg/L –– half the current legal limit –– were about four times more likely to develop thyroid cancer than those drinking water with less than 5 mg/L of nitrate.

Nitrates in the Central Valley

In the Central Valley, this issue is more relevant, as more residents rely on private water systems, like domestic wells, many of which pull water that passes the MCL threshold.

In 2012, a landmark study from UC Davis tested groundwater in parts of the Central Valley and found that more than 90% of the human-generated nitrate contamination came from agricultural sources including synthetic fertilizers, animal manure, and irrigated water.

In this image, nitrates are depicted as small, yellow dots. They start off as nitrogen in the cow manure, then are converted to nitrates in the soil by bacteria. Once they seep into underground aquifers, they can be picked up by groundwater pumps. Illustration by Maggie Gleason.

The water draining from heavily fertilized fields of crops, such as fruits, vegetables, and nuts, which cover much of the Central Valley, becomes saturated with nitrates and carries them into groundwater. In underground aquifers, nitrates can persist for decades, allowing them to accumulate to dangerous levels. If someone in an unincorporated community pumps that contaminated groundwater up through a well and drinks it, the consequences can be deadly.

Several years after Ward published her paper on the connections between nitrate and thyroid cancer in women in Iowa, Colleen Naughton, an environmental engineer at University of California, Merced decided to investigate this in California. She and Arianna Tariqi, a graduate student at the time, found a correlation between nitrate contamination and thyroid cancer incidence among residents in California. They also discovered that disadvantaged communities had twice the rate of cancer incidence compared to non-disadvantaged communities.

“Long term exposure is bad for adults and can potentially cause different types of cancers,” said Naughton. “[Adults] should take it seriously.”

The state’s solution

Folks driving into Modesto, the largest city in Stanislaus County, are greeted by a bowed, steel arch that bears the slogan “Water, Wealth, Contentment, Health”. In 1921, Modesto historian George Henry Tinkham, wrote that the slogan, “tells the story of the condition of Stanislaus County since the Sierras’ waters began irrigating the land”. Today, Modesto’s reality is a far cry from that slogan.

When Maria first moved to Stanislaus County, she knew not to drink the tap water. But it wasn’t until November 2023 that she found out that her well might be contaminated with nitrates, specifically.

“Si antes teníamos precaución por el agua, ahora tenemos más,” she said in Spanish –“If we were cautious about the water before, now we are even more so.”

She also learned that day that she could get her well tested for free, and potentially, free bottled, drinking water.

Maria is not the only resident of Stanislaus County who hasn’t been provided with the safe drinking water resources that she should be receiving. She moved to the area in 2021, about a year after the Central Valley Water Board introduced a program to reduce nitrates in the Central Valley. The program, the Central Valley Salinity Alternatives for Long-Term Sustainability (CV-SALTS) Nitrate Control Program, aims to reduce nitrate discharges into surface and groundwater to restore groundwater safety.

The program requires landowners such as farms and feeding lots to reduce the amount of nitrates they discharge into groundwater and provide free replacement drinking water for residents. Many of these nitrate polluters in the Central Valley, which includes Maria’s home in Stanislaus County, have banded together into six groups called “management zones.”

The management zones claim to have tested more than 2,000 wells and provided more than 1,000 households in the Central Valley with free drinking water.

However, researchers from Santa Clara University’s Environmental Justice and the Common Good Initiative and the non-profit California Rural Legal Assistance (CRLA) say that the nitrate polluters aren’t doing enough to ensure water safety. These researchers have conducted their own study. By analyzing state nitrate data and surveying residents door-to-door, they’ve found that the Nitrate Control Program is not repeat testing wells enough, and is failing to provide sufficient access and knowledge of well-testing and free, bottled water to residents living in areas of the Central Valley most contaminated with nitrates.

“Si antes teníamos precaución por el agua, ahora tenemos más,” she said in Spanish –“If we were cautious about the water before, now we are even more so.”

Door-to-door

The researchers wanted to know how familiar Central Valley residents were with the well-testing and drinking water services that nitrate polluters are supposed to provide.

So, first, the researchers mapped the parts of Modesto and Turlock that are closest to some of California’s largest animal farms, which researchers believe are some of the largest sources of the Central Valley’s nitrate pollution. These large animal farms house hundreds to thousands of animals, which can produce massive piles or pools of manure. Nitrogen-containing chemicals seep from the manure into the soil, where microbes convert the nitrogen into nitrates that pollute nearby groundwater.

Many Central Valley residents also live on or near these large animal farms, so they drink water from wells that are at high risk for nitrate contamination. The Central Valley’s nitrate control program therefore requires these polluters to provide safe drinking water services, including testing wells for nitrate contamination and providing free drinking water, to residents who draw water from the polluted wells.

But the research collaboration found that many of these large animal farms didn’t have publicly available data on nitrate contamination of nearby wells, which means that the landowners might not be testing their wells at all. The researchers identified 416 large animal farms within the Modesto and Turlock basins. They found that the vast majority of these farms – 382 out of 416 – were not testing whether their well water was contaminated with nitrates. And more than half of the farms that were testing their wells – 18 of 34 – found illegally high levels of nitrate contamination.

The researchers soon found out that residents living near contaminated wells didn’t even know that they had the legal right to access free, bottled drinking water.

In August 2023, the researchers walked to residents’ houses near large animal farms to speak with people face-to-face. The researchers found that Latino residents were less likely to know about well testing and water delivery programs than white residents; three-quarters of Latino residents had never heard of these programs, compared to one-third of white residents. And 90% of Latino residents claimed that they never used tap water for drinking and were driving to town to buy bottled water, rather than accessing free drinking water that nitrate polluters are legally required to provide.

“This is an injustice that we need to start fixing now,” said Samantha Lei, an undergraduate researcher who was a part of the canvassing team.

“We know that this is not only a problem in Modesto and Turlock,” said Jake Dialesandro, a remote sensing scientist at Santa Clara University. He said it’s a known problem in the six groundwater basins with the highest amount of nitrate contaminants.

Well-testing trepidations

The team found that part of the reason why more residents aren’t accessing water safety measures is that they are afraid to do so. Many residents, especially Latino residents, who live near nitrate polluters are afraid to irritate their landlords or employers by requesting that their wells be tested for nitrates.

One dairy worker, for instance, told the researchers that his landlord said, “’If you don’t like something, you can leave.”

Another dairy worker was concerned about applying to the free programs because he didn’t want his landlord or employer to think he was doing something behind their back.

“That was kind of shocking to me,” said Rosa Torres, a community worker at California Rural Legal Assistance. She said the short-term risk of losing housing or employment weighs on Latino farmworkers and dairy workers more than the long-term risks of nitrate exposure.

Parry Klassen is executive director of the Valley Water Collaborative, the management zone that is supposed to provide water safety services to the area where Maria lives. He says that he knows that inequity is preventing many residents from accessing the services to which they are entitled.

Landowners are reluctant to test their wells because they fear that their property will lose value if it’s found to harbor nitrate contamination, he says, though that hasn’t happened to Klassen’s knowledge.

Klassen has tried to encourage residents to access services through a door-to-door outreach campaign, though only 16 of about 1,000 residents responded to the campaign. The management zone he oversees now offers a $50 incentive to residents who successfully refer their neighbors and friends to the program.

The biggest challenge is “just getting people to apply,” said Klassen.

“This is not just Valley Water [Collaborative], but all the management zones,” said Klassen. “They hold community events, they knock on doors, they hire these high-dollar outreach companies which don’t come up with anything better than what we’re doing.”

The state responds

To provide greater access to safe water, the research team asked the Central Valley Water Board to eliminate the provision that requires tenants to obtain landlord permission for well-testing. They write “Tenants, like all residents, deserve access to clean water.”

But the Central Valley Water Board states that these instances of landowners refusing to have their tenants’ wells tested has “proven elusive”.

“People who don’t own their own homes shouldn’t have to get permission from their landlords or employers in California, because drinking water should be a basic right,” said Torres.

In their public comments, they argue that California needs a monthly well-testing system and they urge the state to compel farmowners to test their wells and secure water for tenants whose well-water is contaminated.

“Public comments have had a real effect on changing the course of programs like CV-SALTS,” says Stewart-Frey. “There is already more outreach, more accountability, more data transparency, better science, and more water testing because of what we have pushed for.”

Today, Maria worries about her health. Now that she knows her water could be contaminated with nitrates, she avoids brushing her teeth and preparing her food with tap water. For months, she waited for the management zone to test her well.

© 2024 Andrea Tamayo / UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

Andrea Tamayo

Author

B.S. (microbiology) B.A. (international studies) University of Florida

Internships: Stanford School of Medicine and Your Local Epidemiologist

As a medical scribe, I chronicled hundreds of patient narratives during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare workers treated patients for symptoms such as rattling coughs and swollen toes, but patients’ feelings of fear, isolation and confusion often persisted.

The infodemic—an overabundance of information, some accurate and some not—plagued people as much as the pandemic did. But many healthcare workers offered patients clarity through empathetic conversations.

I sought clarity by studying why diseases like COVID-19 spread across societies in an epidemiology lab. But I felt disconnected to the singular lives and stories impacted by the diseases I studied.

I realized that science communication was the root of connection between healthcare workers and patients, and researchers and the public. Today, I fill my cravings for clarity and connection by writing stories to demystify disease.

Tessa Wells

Illustrator

B.S. (wildlife biology and studio art) Lees-McRae College

Internship: Sylvan Heights Bird Park and Monterey Audubon Society

I have always had a desire to connect my passions. To capitalize on the relationship between art and science and share the wonders of the natural world. Being raised in Burlington, a small city in the piedmont of North Carolina, I grew up with a passion for wildlife that has spilled over into my professional career. While double majoring in Wildlife Biology and Studio art at Lees-McRae College in North Carolina, I explored the connection between art and science and my own experiences within both. These connections led me to the world of Science Illustration, and through the Science Illustration Certificate Program at California State University, Monterey Bay I have had the opportunity to explore new mediums, subjects, and become even more inspired by the world around us. I have a special interest in avifauna, and a growing intrigue for insects and plants. Though I have recently found a passion for digital art, traditional media such as acrylic and oil painting continues to be my favorite. I hope to continue to share and explore my passion for the natural world through illustration, and inspire others to share my wonder.

Margaret Gleason

Illustrator

B.S. (biology) Saint Mary’s College

Margaret Gleason is an illustrator and researcher originally from Columbus, Ohio. She has always loved studying the natural world and pursued a degree in biology concentrating in ecology and evolution. Her curiosity has led her to develop animal behavior research and travel the world experiencing different environments and cultures. Margaret’s experience and knowledge help inform her illustration as a form of communication. She aims to inspire others to be curious about the world around them through her artwork.