Making waves: Transgender ocean scientists fight for equity at sea

While various state and federal lawmakers propose anti-trans legislation, transgender and gender diverse scientists and their supporters are speaking out and pushing back with clear recommendations for policy improvements aboard oceanographic research vessels, Sierra Bouchér reports. Illustrations by Arin Vasquez.

Illustration: Arin Vasquez

Mar Arroyo had just embarked on a fresh start.

Swathed in a neon snowsuit and standing on the deck of Aurora Australis, a 311-foot icebreaker ship bound for the Southern Ocean, Arroyo awaited roll call with his fellow ocean scientists. His shoulders were weighed down from the life vest he had donned for a training exercise, but Arroyo was excited. It was 2016, and this was his first research cruise since his medical transition. “I needed to do it that summer. This was going to be my opportunity to start with a new name, new pronouns,” Arroyo said.

But as roll call began, Arroyo’s stomach clenched with embarrassment, sweat pooling in his stifling snowsuit. The chief scientist had called out Arroyo’s previous name, and even mispronounced it so it sounded extra feminine. Arroyo replied “Here,” but his eyes weren’t on the chief scientist – they were scanning the crowd, looking for anyone who may have noticed.

The next time there was a roll call on the ship, Arroyo’s fear came bubbling to the surface again. This time, the chief scientist called Arroyo’s name correctly, but it would be years before his worry subsided. It wasn’t until 2018, when he was able to legally change his name, that the blanket of fear of someone discovering his deadname, or his name given at birth, was lifted off of him, Arroyo said.

Arroyo, a chemical oceanographer at the University of California, Santa Cruz, isn’t alone in this experience. In August 2023, Arroyo and a group of transgender ocean scientists reported on the pervasive harassment and obstacles they experienced during field research, and published a list of recommendations to improve the experiences of trans people on research cruises. With this unprecedented publication, Arroyo and his coauthors hoped to convince leaders in ocean research to protect trans people by updating outdated policies aboard ships. Research institutions are beginning to take notice, but some may be unable to counter the harmful impacts of state anti-trans legislation.

Unwelcome

On research vessels in the middle of the ocean, transphobia is built-in. Research cruises are organized with biological sex and legal name at the forefront of decision making.

Ship ‘berths,’ or rooms, are designated as male or female quarters, with two people – traditionally of the same gender – sharing each room. When a scientist signs up for a research cruise, they must submit official documentation, such as their birth certificate or passport. The gender recorded on those official documents dictate berth assignment, and birth names are used for muster lists and roll calls, which are often posted publicly. For someone who identifies with the gender printed on their official documents and the name given to them at birth, this isn’t a problem. But for trans people who identify as a different gender, these assumptions can feel tortuous. Studies have shown that 55% of LGBTQ+ geoscientists have felt unsafe during fieldwork, and this can affect their choice to be ‘out’ or not.

“The way boats are run is for cis[gender] people,” said Talia Evans, a chemical oceanographer at University of California, Santa Barbara and coauthor of Navigating Gender at Sea, the paper written by Arroyo and others and published in the scientific journal AGU Advances.

Each day at sea can cost tens of thousands of dollars, so science continues around the clock to maximize efficiency. This means most scientists on board must work grueling 12-hour-plus shifts. The long hours, often hazardous working conditions, and the stress of isolation piles up, leading to rampant mental anguish even among non-minority scientists, as a 2022 survey of ocean researchers found.

For some, these experiences have been too much. Minorities have a large attrition rate in the sciences. Though more women than ever are entering the sciences, they aren’t yet well-represented among faculty and other positions of power, and the same can be said for gender diverse people.

But others, including Mar Arroyo, stay in the field they love despite the pain and discrimination that often comes with it.

Watery origins

Growing up in Throggs Neck in the Bronx, Arroyo’s aunt would watch him and a gaggle of other children, taking them to the beach nearly every day in the summer, and then to the public library to borrow nature documentaries. Between floating in the waters of the Long Island Sound and soaking up knowledge about the sea, Arroyo’s love of the ocean grew. In high school he excelled in chemistry classes, and figured he would pursue it as a career, forgoing his love of the ocean. It wasn’t until he began researching college majors that he found the perfect way to meld the two.

As a rising senior at the University of Miami, Arroyo finally got the opportunity to take his passion to the field. His first cruise was the summer of 2015, launching from Hawaii and chugging toward Alaska over the course of 30 days. He worked the night shift, spending long predawn hours harvesting samples of carbon from the ocean. He studies those same samples now for his doctorate research. Throughout Arroyo’s career as a chemical oceanographer, his research has focused on understanding carbon cycling in our oceans, and what they mean for climate change.

Around the time of the 2015 cruise, Arroyo had begun to consider gender transition as something that may make him happier in life, but he was worried about it affecting his budding career.

“But one thing that really helped me was that on my first cruise, there was another trans man,” Arroyo said, awe in his voice. “It was like, wow, I think there’s a lot I can learn from this person.”

Arroyo and this other scientist talked extensively about their experiences, and the resources Arroyo would need to transition. Their discussions solidified Arroyo’s decision.

“It showed me that you can have both,” said Arroyo. “You can be your true lived self while also maintaining friends and a career and a livelihood. It took a lot of scariness out of it. Like look, this guy is doing it! I can do it.”

So, Arroyo made the leap. Upon graduating from the University of Miami in 2016, he began his transition.

Broadly speaking, ‘transition’ can include legal, medical and social transition. Legal transition may mean updating official documentation like a birth certificate, driver’s license and passport, which may not be possible depending on the laws of the person’s birth state and state of residence. Some states require medical transition, such as certain surgeries, before legal transition is possible. Social transition includes altering certain aspects of presentation to help a person be perceived as their desired gender, such as clothing, name or pronouns.

“For me, changing my name was more than just the name I write on a paper,” Arroyo said. “It’s about feeling safe.” Studies have shown that changing a legal name and gender marker to reflect a person’s identity can improve mental health among trans people, and can help build mental resilience in the face of harassment.

Arroyo began his medical and social transition before starting graduate school in 2016, but he hadn’t been able to legally transition yet. This meant that on the Aurora Australis in December 2016, Arroyo was assigned to the ‘female’ berth, or set of rooms. This assignment was plucked directly from the ‘F’ gender marker on his documentation, but didn’t take into account his identity or presentation. Even if it weren’t for the roll call, this berth assignment effectively outed Arroyo as trans – a painful and potentially dangerous position for a trans person to be in.

“Do any of these gruff boatmen know [about me], are they gonna throw me off the side of the boat?” Arroyo said. “That’s a huge exaggeration. But you know, [being outed] can lead to really, really uncomfortable situations when you’re hundreds of miles away from cell phone service or anything that could give you some safety and comfort.”

Queer Siblinghood

Even with higher rates of harassment and unique difficulties, many trans and gender diverse scientists still go to sea as part of their careers. Leaders on these ships have made efforts in the past decade to rectify the prevalent harassment of women aboard research cruises. Now there are explicit avenues for reporting mistreatment, but if respect for trans people is not specifically outlined in community rules, it becomes harder for trans people to report any wrongdoing.

Nonetheless, transgender scientists continue to persevere. They’re out on the waters doing challenging work, trying to improve science and the world. But the added stress of not conforming in a society that is still largely built around binary expressions of gender can make these isolated ships that much more desolate.

“You’re under a wall of microaggressions…” said Evans, citing constant occasions of misgendering and deadnaming. “It can seriously harm relationships with someone who could be your mentor.”

For researchers like Colette Kelly and Jules Middleton, who both use they/them pronouns, very few people ever make the effort to gender them correctly. This leads to weeks of constant misgendering, which takes an intense mental toll. “The problem is the people I would have reported to are the people who are misgendering me,” said Kelly, an ocean data scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Kay McMonigal, transgender and nonbinary person and physical oceanographer at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, similarly felt that the experiences for transgender people on research cruises needed improvement. “I hadn’t seen it discussed very well anywhere,” McMonigal said. To try to do something about it, they reached out to their community of trans and nonbinary ocean scientists in 2022, and pitched an idea: creating a list of recommendations for how to make ships safer and more inclusive for trans and gender diverse scientists.

With 13 different trans and gender diverse scientists across oceanography co-writing the paper, Navigating Gender at Sea aims to be a guiding document for ship leaders.

“A lot of people have feelings of, ‘Well, I want to help but I don’t know how to, I don’t want to mess up,’” said Dani Jones, an oceanographer at University of Michigan and coauthor of the new paper. “The hope is that we’re telling people really clearly: here’s what to do from our perspective.”

McMonigal, the lead author on the paper, wanted as big a group as possible to write the paper, to bring diverse perspectives and insulate the individuals. The list of recommendations includes ways for leaders aboard ships to support trans folks, such as including pronoun and lived name options on ship rosters as well as educating staff.

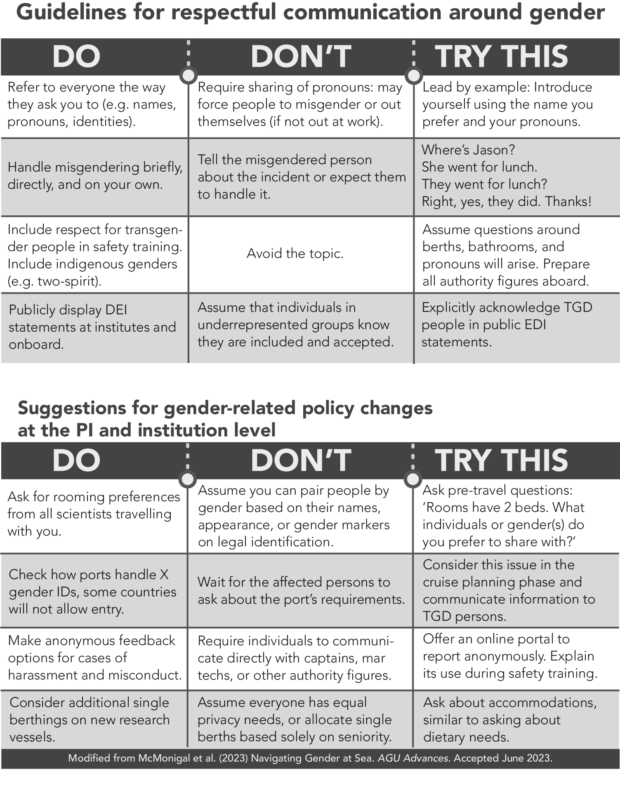

Table of guidelines for respectful communication around gender, and suggested gender-related policy changes, Created by McMonigal et al.

Making Waves

Navigating Gender at Sea is already sparking change.

The authors have been invited to lead multiple workshops and presentations at various conferences across the country since its publication. Arroyo is extremely encouraged by all the changes he is seeing. “This work that we put together shows people that we aren’t just creating policies to look good, we’re creating policies to save people’s lives, ultimately,” he said.

Sarah Huber, Curatorial Associate at the Virginia Institute for Marine Science (VIMS), is leading the charge to spread the word of Navigating Gender throughout VIMS and the organization’s partner institutions. “The lived experiences of [the authors] are crucial for helping other people understand how they can really modify and change their policies and procedures in the field,” Huber said.

Huber is a parent of a transgender child, which further motivates her to push the field to be more inclusive. “I never would have understood all the complexities if I wasn’t trying to do this for my kid.”

Arroyo spoke at a panel in March during the Atlantic Estuarine Research Society annual meeting at VIMS. But VIMS isn’t the only organization taking notice. The Northern Gulf of Alaska Long-term Ecological Research Project and the British Antarctic Survey have also reported using this paper to inform their cruise planning.

The University-National Oceanographic Laboratory System (UNOLS), the coordinating organization for all federally funded research ships owned by universities in the U.S., has also distributed the paper as a recommended resource among their institutions. UNOLS is a significant organization in the field of oceanography, and its distribution of the paper could have a big impact. UNOLS also held a panel discussion with some of the paper’s authors at its Ocean Sciences Meeting in February 2024.

It’s in the best interests of these organizations and science in general to improve equity aboard research vessels, Arroyo said. “I’m on this boat to do good science. And if I’m not feeling comfortable and safe, I might not do good science.”

Much left to do

Despite any institutional willingness to adapt the paper’s recommendations, there is still a large gap when it comes to enforcing any anti-harassment policies. “There’s a lot of sexual harassment that happens on boats. And it may be a repeat offender or a one-off,” Arroyo said. “To me, it doesn’t f–king matter. We need to have consequences.”

Huber said that while in theory there should be ramifications for violating these sorts of policies, the appropriate consequences are not always stated in the policy.

While some institutions have started implementing these recommendations, overarching bodies such as UNOLS don’t have the legal power to mandate or enforce change. This means policy can vary widely from one vessel to the next or be implemented differently because of the university’s state laws and culture.

The legal environments for transgender people have become dramatically different from state to state across the U.S., with many transgender protection and anti-trans bills signed into law even in the short time since Navigating Gender at Sea was published in mid-2023.

“There are a number of states within the United States right now that are the best places in the world for transition, for getting trans care, for easily changing your gender markers, for having court protections,” said Erin Reed, an independent journalist and author of a trans legislation newsletter. “On the other side, there are good 10-20 states right now that are some of the worst.”

Many states have taken extreme measures to roll back the rights of transgender people. While most of these laws target trans youth, unprecedented laws restricting adults have started to pop up in places like Florida, Utah and Kansas. These laws can limit access to healthcare in multiple ways, and even criminalize public bathroom use. For trans researchers, simply visiting one of these states in order to board a cruise could prove hazardous. Reed said there seems to be no end in sight: “It appears that the extreme law or the extreme bill that gets blown away this year becomes the next year’s bill that passes in 15 states.”

While research cruise organizations and universities can’t directly change the laws, it is important for leaders to understand how they may impact their trans scientists. If a cruise is starting or ending in one of these states, transgender scientists may not be able to go without risking their safety, or even jail time.

The 2024 U.S. presidential election could have broad impacts for transgender people across the country, including those who work in ocean research. Many ships are federally funded, and bills that have already been introduced in congress such as the ‘Productivity over Pronouns Act’, which bans “the use of Federal Funds in any program, project, or activity of any agency in the Executive Branch to provide principles, resources, or specific suggestions for gender neutral or inclusive language or inclusive communication principles” could wipe out any progress Arroyo’s paper has made.

Just keep swimming

Arroyo is reaching a critical point in his career. Samples from his very first cruise in 2015, among other data, have informed his PhD dissertation, which he is estimated to finish in Spring 2025. His vital work on anthropogenic carbon release into the oceans could inform policy and work implemented by the federal government to meet their climate goals. However, writing Navigating Gender at Sea has him questioning the traditional path set out for him post-PhD.

For Arroyo, being a mentor in the LGBTQ+ scientist community has become an important role. He is hoping to find a way to pursue science and activism together in his career, he said. “There are ways I can still be a researcher, an oceanographer and a scientist while reaching people and having my experiences [as a transgender man] be a way for others to understand that they can do this too.”

© 2024 Sierra Bouchér / UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

Sierra Bouchér

Author

B.S. (animal behavior, ecology and conservation; digital media arts) Canisius University

Internships: Science, Live Science, NASA Goddard

What is your first memory of nature? My very first memory as a child is of fishing with my father as the iridescent scales of a rainbow trout glinted in the summer sun. My relationship with nature is deeply important to me, and was an obvious choice when pursuing my career. I’ve filmed tigers in India and shore birds on Long Island, studied the historical ecology of giant salamanders, and spread awareness of the prolific turtle trafficking industry in America. With these experiences I have chased unique stories of our intersection with non-human animals throughout my career. Now I embark on a new journey as I begin my path in science journalism. I can’t wait to explore new links between us and our neighbors on this planet we call home.

Arin Vasquez

Illustrator

B.S. (Fine Arts) University of San Francisco

Internship: 3D Modeling and Printing at ReefRenders

Arin Vasquez (they/them) is a queer Latine artist based in Monterey, California. They are currently getting a postgraduate certificate in Science Illustration at California State University Monterey Bay. Their keen interest in science has fostered a tendency towards realistic, observational art, often focused on marine life. Arin’s primary mediums are 3D modeling and printing, as well as more traditional sculpture work. Arin has exhibited work in the Thacher Gallery, the University of San Francisco’s XARTS Gallery, the SOMArts Cultural Center, and the Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History.