Turning the tide: Revitalizing Elkhorn Slough

Researchers and volunteers hope to combat climate change by planting some 20,000 native plants, Tom Garlinghouse reports. Illustrations by Deanna Derosia and Sienna Van Slooten.

Illustration: Deanna Derosia

Flat, muddy marshland glistens in the early morning sun, stretching into the distance. Thick mist swirls lazily as the cackle of geese echoes through the quiet air. There is a tranquility to the scene, a sense, somehow, that time has stood still. At first glance, it feels as if this place—an estuary nestled between green, rolling hills—has always been here, untouched, primeval, and unchanging.

A closer look, however, reveals hints of recent upheaval, such as a hill carpeted with invasive grasses and an expanse of thick, barren mud that should contain a riot of colorful bushes. Together, these belie this sense of an unchanging landscape. In fact, this place—Elkhorn Slough, along the coast approximately 20 miles north of Monterey in central California—has had a tumultuous history.

Over the last century and a half, time and development have left their mark. Farms built in the area have decimated approximately 50 percent of the Slough’s habitat, transforming marshland into mudflats.

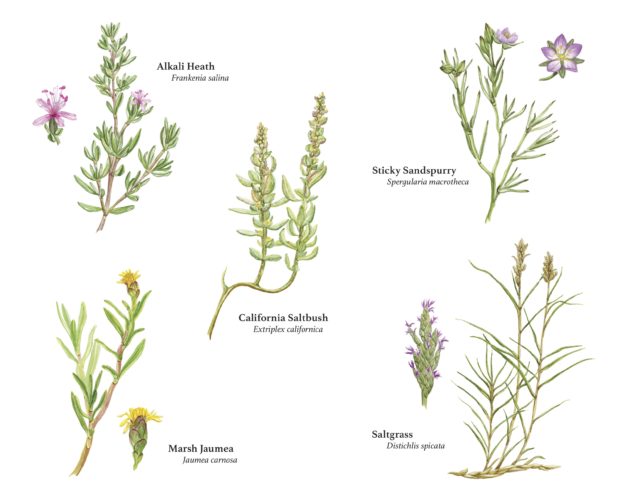

Now, however, a dedicated team of researchers and volunteers is trying to reverse the damage by planting a section of the Slough with native plants. These researchers want to restore approximately 61 acres of land—the equivalent of nearly 55 football fields—by planting some 20,000 plants, including saltgrass, alkali heath and marsh jaumea. If they succeed, they will have restored 10 percent of the Slough’s lost habitat—and, importantly, left a legacy of a repopulated marshland for future generations to enjoy.

Located halfway between Santa Cruz and Monterey, near the town of Moss Landing, Elkhorn Slough is California’s second largest estuary—an estuary, in simplest terms, is a body of water where a river or a stream meet the sea, forming a mix of salt and freshwater. Elkhorn Slough meanders across the landscape—from the air it looks like a giant, irregularly-shaped “S.” It is 7 miles long and covers nearly 3,000 acres, or 4 square miles. It is home to a variety of plants, such as pickleweed and eelgrass, as well as seabirds, wading birds, fishes, shellfish, sea otters, and other mammals.

The team of researchers is focused on restoring Hester Slough, which forms a branching arm along Elkhorn Slough’s southern end. This area was heavily farmed during the late 19th and for most of the 20th century.

The preservation and restoration of coastal habitats—like Hester Slough—are vital in the global battle to curb and allay the effects of global warming, scientists say. They think that marine and coastal environments—such as mangrove swamps, seagrass meadows, and tidal marshlands—are excellent areas for the “capturing and holding” of carbon, a process known as carbon sequestration. Most of the carbon captured in these habitats is stored in plants and soil. Although coastal environments comprise only 2 percent of the world’s ocean area, they nonetheless account for half of the carbon typically stored by ocean environments. The importance of coastal habitats becomes clear when, as many researchers estimate, over 80 percent of the global carbon cycle circulates through the oceans rather than in terrestrial environments.

However, when degraded or destroyed, coastal habitats emit the carbon they have stored for centuries into the atmosphere and oceans and become sources of greenhouse gases. Experts estimate that as much as 1.02 billion tons of carbon dioxide are being released annually from degraded coastal ecosystems, which is nearly 3 percent of the world’s total carbon emissions.

On a global scale, some researchers estimate that human impacts have destroyed 50 percent of the world’s marshland habitats. And it is only getting worse. Other researchers suggest that, worldwide, marshes are disappearing at a rate of 1-2 percent per year. In California, the problem is especially acute. Since the mid-nineteenth century, development and agriculture have destroyed over 90 percent of California’s coastal wetlands.

With such a depressing history of marshland loss, the researchers know that the task of restoring Hester Slough is daunting. Habitat restoration is an imprecise science; scientists are still experimenting with the best ways to restore marshlands and other coastal ecosystems. Whether these replanted native shrubs will survive and flourish is a big question mark. Similar restoration projects, like some in southern California, have not been entirely successful. Hungry birds and other creatures, along with invasive non-native plants, could potentially devastate the seedlings. And, of course, there are any number of unforeseen obstacles—such as poor weather or acts of nature—that could devastate the newly seeded area.

Boots on the ground

The squelch of rubber boots sinking into mud breaks the silence.

“It’s slippery but not as bad as last week,” says a voice accompanying the rubber boots. It belongs to Kerstin Wasson, the project’s principal investigator and the research coordinator for the Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve. The Reserve, which is administered by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), is dedicated to promoting research, education and conservation of Elkhorn Slough.

A week ago, torrential rains coupled with high tides created a veritable quagmire. Now, however, things are beginning to dry out.

Wasson stops in mid-stride and glances up at the clear skies and emergent sun. “This is deluxe fieldwork,” she adds with a little smile.

Clad in neoprene waders, Wasson is small-boned and wiry with closely-cropped hair and sharply focused eyes. She marches through the mud, her boots leaving deep impressions behind her. An invertebrate zoologist by training, Wasson has taught herself just about everything there is to know about the flora and fauna of wetland habitats—and Elkhorn Slough in particular. She can rattle off statistics about historical habitat loss as well as other interesting tidbits.

“We know exactly what the carbon sequestration rate is at Elkhorn Slough, it’s 200 grams of carbon per meters squared per year,” she tells me at one point.

Wasson’s team of two biologists and six volunteers plods along behind her, trudging through the muck as if in slow motion. The team is armed with pin-flags—thin metal stakes with attached flags used to highlight the planting areas—and loaded down with crates of native grasses and plants. They assemble in a small cluster down near the water’s edge, dropping their crates, buckets and pin-flags into the mud.

The two other biologists on Wasson’s team, Karen Tanner and Rikke Jeppeson, begin the task of organizing the gear for the day’s work: hand planting the shrubs in the soft mud. Their volunteers, six young men from the California Conservation Corps, gather around as Tanner explains that the young shrubs will be placed in planting holes called “dibbles,” because the tool used to press the holes is called a “dibbler.”

When orientation ends, the volunteers break into “planting teams,” each supervised by one of the biologists.

Wasson’s team congregates along the water line. She kneels down in the mud, picks a saltgrass shrub out of a crate and stuffs it into the nearest dibble.

“Really wiggle them around to get them in the holes,” she says, demonstrating the best way to plant each shrub.

Ultimately, Wasson says, “We want to create an area that is more resilient for the future so that it’s not just here for today but it’s here for a hundred years.”

Wasson’s team will plant five species of shrubs today: saltgrass, alkali heath, marsh jaumea, sticky sandspurry and California saltbrush. Each of these, along with other species, such as pickleweed, once grew in dense clusters in the area. Plants are vital to nearly every ecosystem on earth but are especially vital to marshland habitats. They attract other species, prevent erosion, provide nutrients to the water, and also filter water, thereby improving water quality. In short, they are building blocks of a healthy, functioning marsh ecosystem, Wasson says.

Five species of California marsh plants. Illustration: Sienna Van Slooten

A little history

Over the last 150 years, however, many of these plants were nearly extirpated as Hester Slough transformed from a vital tidal marshland to an algae-covered mudflat. Marshland, a combination of fresh and salt water, is a haven for plants, but it also attracts birds and animals. A thriving marshland is thus cacophonous and vibrant, home to flitting song birds, scurrying small mammals and raptors soaring overhead. Now, however, large stretches of Hester Slough are gray, flat and un-vegetated, the consequence of many years of sediment accumulation from rivers. The waters are sluggish with very little influx from the ocean. Fewer animals and fewer species live here now than 150 years ago.

This transformation happened gradually. The earliest American settlers grazed cattle here, which didn’t alter the land very much. But by the middle of the nineteenth century, the settlers actively began to farm the land. They started by clearing nearby forests and planting hay and barley. This eroded the rich topsoil that the trees had held in place, depleting the land of vital nutrients.

However, larger-scale projects—and larger-scale damage—followed. Beginning in 1870 and continuing apace for much of the 20th century, settlers diked, dredged and drained the area. Engineers constructed some 60 km of levees and embankments in order to create agricultural land. Without the influx of saltwater, and freshwater diverted to farms, large sections of the Slough dried out.

Tanner explains that marshland acts like a sponge once it is diked off and drained. It dries out, shrinks and sinks. When the Hester Slough area was drained it dropped in elevation, causing the ground to sink to levels too low to sustain marsh plants. Tanner explains that if water is allowed to return to the area the plants will simply drown.

This is exactly what happened when engineers removed the dikes at Parsons Slough, which adjoins Hester Slough to the northeast. Saltwater rushed in and mixed with freshwater. But instead of creating marshland, the water simply drowned the vegetation there.

It became clear that restoring marshland was a much more complicated process than many had thought. Nevertheless, many scientists and conservationists were determined to give it a try.

The Restoration Project

In 2010, a group of scientists and land managers from the Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve created the Tidal Wetlands Program (TWP). This nonprofit organization was dedicated to conserving and rehabilitating parts of the Slough. Realistically, the scientists and managers knew they could only accomplish so much; the organization’s funds would be limited and its managers were still in the process of learning how best to restore marshland habitat. Nonetheless, with an advisory committee of 60 scientists and the 15 different agencies that had jurisdiction over the Slough, members of the TWP began devising a plan for restoring marshland habitat.

“When we began this, we looked at the big picture,” says Monique Fountain, the director of the TWP. After a long process of consultation, they decided to start a plant restoration project.

Equipped with mostly public funds, they first arranged for a fleet of trucks and bulldozers to move tons of soil and dump it onto the mudflats. It was important to raise the elevation of the land so that the re-planted vegetation wouldn’t drown.

“The elevation of the marsh is critical to its long-term sustainability,” says John Callaway, an oceanographer and ecologist at the University of San Francisco.

For much of 2018, the Slough was a chaotic scene of tractors, trucks, dredgers, and bulldozers, moving, dumping, and spreading out and compacting soils. Taking soils from the Pajaro River but also the surrounding hillsides, these earthmovers gradually built up the landform back to its previous height. In all, the excavators used approximately 200,000 cubic yards of soil.

Then, in August, the researchers assembled a team for the next phase: the hard work of planting, which began in January 2019. By the middle of the month, they had already accomplished a lot.

A cause for optimism

After planting all morning, Wasson stands up. Her waders are smeared and clumps of viscous mud cake her boots. All this planting has left the mudflat a morass of footprints and deep indentations. While the team has been conscientious about tramping around only in designated areas, it is almost impossible not to have an impact on the muddy ground. Mud clumps like blocks of thick concrete on all the boots of the volunteers.

Wasson takes a moment to survey the team’s work, her eyes falling on the long line of multi-colored pin-flags stretching out into the distance. She has a tired but satisfied look on her face. Each flag marks a newly planted locale. Today’s flags coupled with the previous week’s planting flags indicate that the team has covered a lot of ground. But the team still has a lot of work to do. Wasson explains that the project is one of the largest marsh restoration experiments in terms of number of plants.

The plants are organized in several plots, each one a rectangle measuring 30 x 35.5 meters. These plots, in turn, are divided into two different sections. The plants in each section are planted according to two different patterns: plants in some sections are planted in evenly spaced rows, while plants in other sections are planted clumped together. The plants are arranged this way because the project is not simply restoration but also contains an experimental component. Wasson and her team will test how well the plants in these two different arrangements grow. The results will help guide future restoration projects here and at other salt marshes.

Although Wasson suggests that it’s too early to quantify the success of their carbon sequestration, most of the previously planted shrubs are surviving, which is encouraging news for the shrubs planted today.

In the past, plant restoration projects have not always been successful. Joy Zedler, emeritus professor of ecology and botany at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a major pioneer in the study of wetland restoration, relates how her replanting project conducted at two tidal marshes in southern California was a failure. Nearly all the 5,000 plants she planted died as a result primarily of smothering by sediment deposition and algal blooms. Still, she is enthusiastic about Wasson’s project, especially about the melding of science and habitat restoration.

“Every restoration project involves uncertainties, so the best approach is to use field experiments to learn while restoring,” she says.

She believes there is a high potential to learn from the different patterns of planting Wasson’s team is using. Indeed, many scientists and conservationists hope that the lessons learned from this project will help to restore similar estuaries and sloughs worldwide.

Ingrid Parker, a plant ecologist at UC Santa Cruz, concurs. If the planting is ultimately successful, “This project could be a model for future projects,” she says.

But it all depends on whether the plants survive over the next several months—a prospect that is by no means certain.

Still, Wasson is optimistic that at least for Elkhorn Slough the tide might be changing.

“We’ve lost 50 percent of our marsh,” she says, “but here we’re restoring 10 percent of it.”

She pauses for a brief moment, and then adds: “I feel I’m really taking care of this place and can really see my legacy not so much in terms of publications in one field but that I’ve been able to move the needle in better policy and more restoration projects.”

Ultimately, Wasson says, “we want to create an area that is more resilient for the future so that it’s not just here for today but it’s here for a hundred years.”

© 2019 Tom Garlinghouse / UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

Tom Garlinghouse

Author

Ph.D. (Anthropology/Archaeology) University of California, Davis

Internships: UC Santa Cruz News Service, Inside Science, Monterey Herald, Princeton University

As evening fell on San Clemente Island, we staggered back to camp. My crew and I had spent all day digging through the remains of a Native American village on this tiny island 50 miles west of Los Angeles. As we sat around the fire, a journalist interviewed me about ancient fishing strategies. Our conversation rekindled a long-dormant desire to combine my loves for writing and archaeology.

After graduate school, I went to work as an archaeologist, studying Native American sites in California. But that evening on the island never strayed too far from my thoughts. Now, after twenty years, I have finally decided to pursue my dream of becoming a science writer. After entrusting my stories to other journalists, I will now try my own hand at writing these tales from the past.

Deanna Derosia

Illustrator

B.S. (biology, Studio Art) Florida State University

Deanna is an illustrator and biologist born and raised in the sunny Treasure Coast of Florida. Growing up next door to nesting sea turtles, strolling alligators, and bright pink spoonbills ignited her curiosity for the natural world, and inspired her to preserve unique habitats like Florida’s for generations to come. Unable to chose between her two loves of art and science, she decided to get her Bachelor’s degree in Biology (with a concentration in Evolution and Genetics), and Studio Art at Florida State University.

After graduating, she pursued the field of science illustration, working as a freelance illustrator and research assistant for 5 years with conservation groups across Florida, her roles ranging from a sea turtle nesting surveyor, to a seahorse aquaculture assistant, and a muralist for the Pelican Island Audubon Society. She later grew her skills as a science illustrator at CSUMB’s renowned Science Illustration post graduate program, and will soon start an internship as a mural assistant with InkDwell. She hopes to continue with science illustration through her business “Sealacanth Studios” to help others explore our natural world, discover its oddities, and learn about their own next door critters through the storytelling quality of art.

Sienna Van Slooten

Illustrator

B.F.A Wheaton College

Internship: Canyon Road Contemporary Art Gallery

Sienna Van Slooten is a science illustrator and nature artist from Santa Fe, NM. In 2016, she graduated with a BFA in Studio Art and Italian Studies from Wheaton College in Norton, MA.

Professionally, Sienna strives to create both fine art and science illustration. Having grown upwith her mother and grandmother as role- artists, she has always felt drawn towards the art world. After graduating, she worked as a curator at the Canyon Road Contemporary Art Gallery for two years and gained experience handling valuable original artwork. Here she also worked one-on-one with a cohort of artists in portfolio development and exhibit curation. During this time, Sienna decided she wanted to pursue her own art career and was drawn towards the science illustration field for its close connection to the natural world. Nature has been Sienna’s ongoing inspiration in her artwork and in now pursuing science illustration with a focus on botanical art, she feels she has found the perfect balance between the worlds of art and nature. Sienna’s goal and passion is to increase awareness of the beauty and complexity found in nature through her

artwork.