Earlier this month, I joined biologist Steve Haddock and his research group from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute for a daylong cruise aboard MBARI’s R/V Rachel Carson. We left from Moss Landing, CA and travelled about 15 miles out into Monterey Bay, passing pods of porpoises and sea lions along the way. Haddock takes these cruises roughly every six weeks, and has done so for years: the charmed life of a scientist working at one of the world’s most sophisticated marine research facilities.

Earlier this month, I joined biologist Steve Haddock and his research group from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute for a daylong cruise aboard MBARI’s R/V Rachel Carson. We left from Moss Landing, CA and travelled about 15 miles out into Monterey Bay, passing pods of porpoises and sea lions along the way. Haddock takes these cruises roughly every six weeks, and has done so for years: the charmed life of a scientist working at one of the world’s most sophisticated marine research facilities.

What were we searching for? Jellies. Haddock builds phylogenies, or family trees, of jellies to understand how this diverse group of animals has evolved through time. While most of us associate ‘jellyfish’ with domed globs and stringy tentacles, this broad term actually applies to animals with a much wider variety of shapes and lifestyles. Haddock collects at least a dozen samples each cruise, and then brings them back to the lab to parse apart their genes. He is especially interested in mapping out how bioluminescence — the natural ability to glow — has evolved independently in different groups of jellies through time.

The team uses different methods to collect jellies depending on the species of interest. Species that float near the surface of the ocean, for example, provide a great excuse to scuba dive and collect by hand. But this cruise aimed for deeper species, pulsing at depths of 400 meters, and required the help of an underwater robot retrofitted by MBARI engineers for these purposes.

The following slideshow documents the fieldwork:

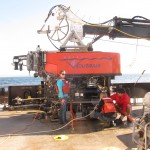

- Remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Ventana — Spanish for ‘window’– joined MBARI in 1988. MBARI engineers have revamped and upgraded it several times since then, but it still maintains its classic blocky ‘80s-robot look.

- Ventana weighs 5,660 pounds. This hefty load consists of various sampling devices, an HD camera, sensors that measure the temperature and chemistry of ocean water, and many wires transmitting information across these devices.

- A 2,300 meter-long tether, or ‘umbilical cable’, anchors Ventana to the boat.

- The control room within the boat looks like the inside of a space ship, especially with marine debris passing by the camera like a meteor shower. The walls are painted black to help increase the contrast of the images on screen.

- Sea nettles like this one are common to Monterey Bay — I spotted at least 3 floating along the surface throughout the day.

- Pilot Mike Burczynski has mastered the art of robotic sample collection.

- As co-pilot, Haddock controls the camera.

- Burczynski and Haddock work together to collect specimen of interest, like this bioluminescent ctenophore.

- Ventana is equipped with two types of collection devices: 1) Plastic cylindrical tubes with lids that swing open and closed at the pilot’s command…

- …and 2) A robotic suction arm that slurps studier specimen directly out of the water into a collection tank tucked within the body of the ROV.

- This green siphonophore is a stunning example of a jelly that just doesn’t quite fit that classic bell-shaped stereotype.

- Once the team ends the dive, Ventana takes about 45 minutes to travel the 400 meters back up to the surface. The ship’s crew has established a safe and efficient maneuvering system to pull the hefty robot back aboard.

- The team then gathers the collection bins off of Ventana, empties the samples into glass containers, and stores them in coolers.

- A baby squid: not a jelly, but fascinating by-catch nonetheless.

- Haddock (right), his research technician Lynne Christianson (center), and graduate student Meghan Powers (left) rinse off Ventana with fresh water once all the samples are safely tucked away. Then, for the next hour and half, the team has time to enjoy the sun while we make our way back to shore.