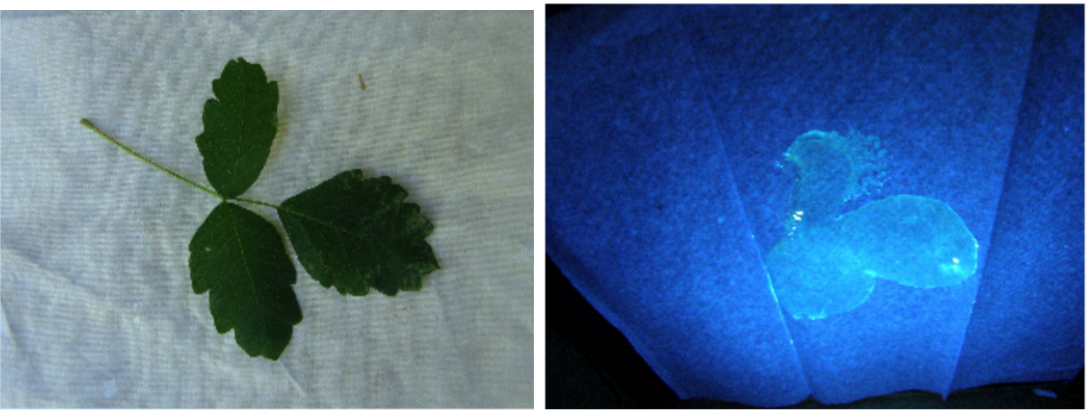

Beautiful as they are, these shiny leaves are covered with itch-inducing urushiol. (Photo: Wikipedia Commons)

Nothing ruins an invigorating day spent communing with nature more than the sight of poison oak. One minute you’re admiring the expansive beauty of an old oak tree, and the next you’re agonizing about whether you may have accidentally brushed up against its greasy little red-leafed cousin. Even if you avoid poison oak like the plague for the rest of the hike, you realize there’s still a good chance you’ll be itching and oozing in odd places before the weekend is over. You can thank urushiol for this experience.

Urushiol—the itch-inducing chemical found in poison oak and ivy—causes nasty allergic reactions in 70 percent of adults. After only a few minutes on the skin, it begins the process of activating an immune response that reveals itself a couple of days later as a red itchy rash. To make matters worse, it sticks not only to skin, but also to hiking boots, clothing, backpacks, and dogs, where it remains active for months or even years. Like a bad memory that keeps resurfacing, urushiol never seems to go away. Fortunately for those of us who suffer from the oozy after-effects of urushiol contact, chemists at UC Santa Cruz have developed a spray that glows when it lands on the stubborn substance. Once detected, urushiol can be washed off using detergents such as Tecnu.

Rebecca Braslau, the lead investigator of the team that developed the spray, had a good motivation. Unlike her husband and dog, she’s highly allergic to poison oak. Her husband eventually learned to avoid the plant for her sake, but so far her dog couldn’t care less about traipsing through its greasy leaves. Braslau says she dreams of a day when she’ll be able to spray her concoction onto her dog, husband, and everything they may have touched, allowing her to detect minute amounts of urushiol before she invariably comes into contact with it.

Braslau used her skills as an organic chemist to tackle the problem of invisible urushiol. Along with graduate students MariEllen Cottman and Frank Rivera, and undergraduate Erin Lilie, she tethered a fluorescent dye to a quencher molecule called a nitroxide. The quencher normally prevents the dye from glowing, much like a dark blanket would do when thrown over a lampshade. Throw urushiol into the mix, and the quencher interacts with the sticky substance instead — effectively pulling the blanket from the shade. When a hand-held black light is shined on the area, the dye glows brightly, revealing even tiny amounts of urushiol.

Gotcha! Urushiol is detected on this paper towel months after the poison oak leaves were removed.

(Photo: Rebecca Braslau)

The structure of the urushiol molecule is designed to get under our skin. Along with neurotransmitters like adrenaline, urushiol belongs to the chemical family called catechols. The molecule looks somewhat like a kite: a polygon shape with a long tail dangling down. While all catechols have the polygon structure, they vary in regard to their tails. Urushiol’s tail is quite long, which makes the molecule greasy and allows it to seep into the skin. There, the polygon portion of the molecule interacts with proteins inside the body to form the allergen that ultimately triggers the itchy response.

Once in the skin, hungry immune cells gobble up the urushiol allergen and unwittingly display their digested wares to killer T cells for perusal. Although they normally concern themselves with wiping out virus-infected cells and clearing infections, T cells can sometimes develop a grudge against harmless substances like urushiol too. In people who’s T cells react with urushiol, the cells wreak havoc in the exposed area, killing all cells that wave the urushiol flag. This reaction leads to a blistering, horribly itchy rash that can persist for weeks in some people. Because the T cells multiply each time they encounter the substance, our reactions to urushiol tend to get more severe over time.

Poison oak and ivy cast a discomforting shadow across the country, where 10-50 million Americans suffer from exposure each year. Workers compensation data indicates that urushiol exposure accounts for 10 percent of time off work for Forest Service employees. Because of its widespread prevalence and the large majority of sensitive people, the ability to detect and remove urushiol could have quite an impact. “I’m really hopeful that this could mitigate suffering for hundreds of thousands of people,” says Braslau.

Despite the excitement about the potential benefits of the spray, the product has a way to go before it’s displayed next to Tecnu on the shelves of REI. While Braslau doesn’t expect the dye to be harmful, toxicology studies still need to be conducted to make sure. Her lab is also tinkering with different dyes that could work better in the field. As it stands now, the dye only glows under a fluorescent “black light.” Cheap hand-held black lights are widely available, but Braslau’s team hopes to develop a dye that glows without the extra help.

If she succeeds, one day misting your clothes, boots, dog, and entire family with fluorescent spray could become just another part of walking in the woods.