Giants

The critically endangered giant sea bass is making a comeback. Alex Fox talks with marine biologists and fishers about what the future holds for the king of the kelp forest. Illustrated by Laurie Sawyer.

Illustration: Laurie Sawyer

On August 29th, a fishing boat called the “Reel Fun” motored out into the hazy sunrise from Dana Point Wharf in Orange County. The goal was to capture endangered giant sea bass — fish that can be bigger than a silverback gorilla and old enough to earn a senior-citizen discount. Marine biologist Larry Allen, who organized the voyage, had already made two unsuccessful bids to apprehend this hulking quarry.

Allen and a hand-picked crew of fishers hoped to land several giant sea bass unhurt and alive. Once he had captured the giants, Allen hoped he could entice the fish to sing. If confirmed, the mating song of the giant sea bass would begin to reveal their mysterious world, and aid in the species’ tenuous recovery from the brink of extinction.

A full-grown giant sea bass is the king of the kelp forest ecosystem, eating anything that fits in its cavernous mouth. As top predators, these giants help control the populations of the fish and crustaceans they eat, preventing any one species from running amok. The giants, formerly known to fishers as black sea bass, lurk among the sun-dappled kelp beds of the California coast from Monterey all the way into Mexico, though they are seen only rarely north of Point Conception near Santa Barbara.

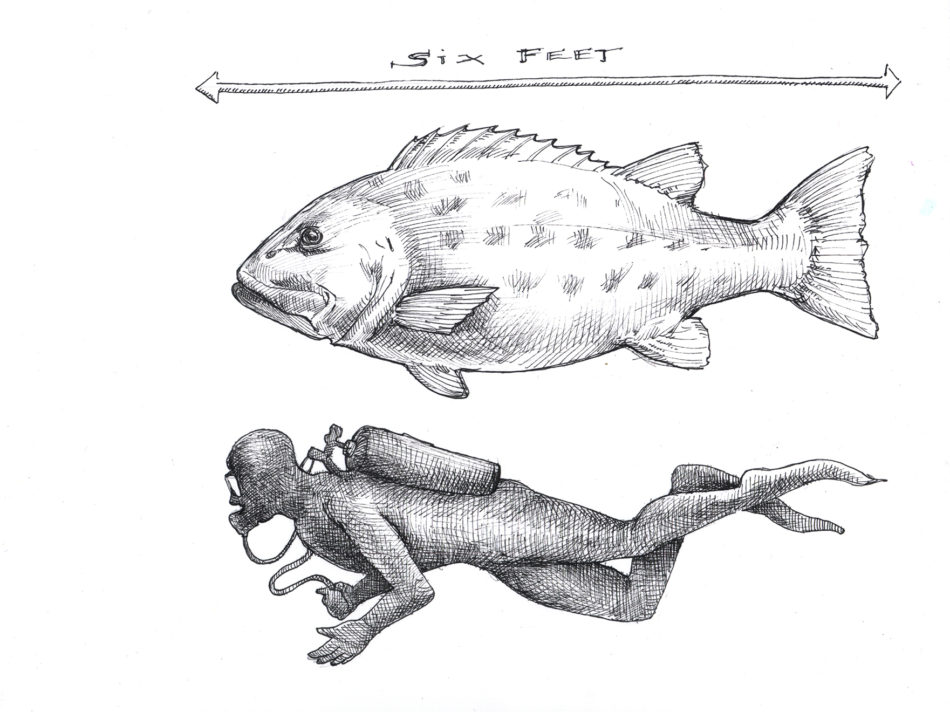

A full-grown giant sea bass can be more than 7 feet long and weigh in excess of 500 pounds. Illustration: Laurie Sawyer

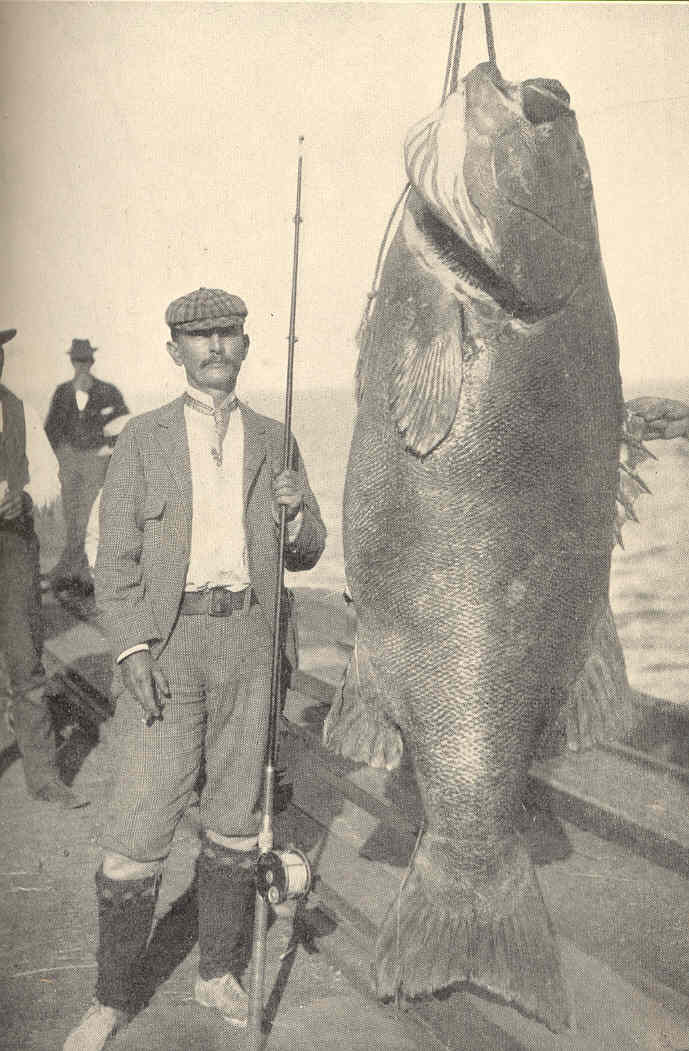

Each summer the giants gather in the kelp forests around the Channel Islands and Catalina Island off the coast of Los Angeles to spawn. Fishers used to haul lunker after lunker out of the deep during these gatherings. Black and white photos from the fishery’s heyday show men dwarfed by their catch’s bulk.

Fisher with a giant sea bass caught near Santa Catalina Island circa 1900.

Photo: Charles Frederick Holder, via Wikimedia Commons.

California banned fishing for giant sea bass in 1982 after decades of overfishing. Now, giant sea bass are coming back – so much so that some anglers say it’s time to reverse the ban on catching these fish. Allen thinks that’s a bad idea, and estimates that the giant sea bass population is still 90 percent below its historic numbers. He thinks a sustainable fishery isn’t possible until we better understand this species, and has spent the last 10 years working to fill that knowledge gap. Now he’s studying giant sea bass reproduction, including their song.

“We’ve made progress, but fishers need to understand that the cake isn’t ready yet,” said Chris Lowe, a shark expert at CSU Long Beach who’s been tracking the movements of giant sea bass with acoustic tags.

Allen, 67, typically wears a ball cap and t-shirt emblazoned with fish over his white hair and sun-spotted arms. He spent much of his southern California youth around the water: “I started fishing when I was five, and back then seeing a giant sea bass was extremely rare,” Allen says.

Giant sea bass vanished from the undersea landscape after overfishing nearly eradicated them. The fishery collapsed in the ’30s and declined to almost nothing. Though California banned fishing for giant sea bass in 1982, scientists mostly credit the giant sea bass’s recovery to a 1994 ban on nearshore gill netting — an effective but indiscriminate fishing method in which fishers deploy nets up to a mile long.

In the early 2000’s, as giant sea bass began to recover, Allen began encountering them on his dives. Allen scoured the literature for some explanation for their reappearance. He discovered that scientists knew almost nothing about a fish that can exceed 7 feet in length and weigh more than 500 pounds.

“What haunts people is this memory of bringing in a five-or ten-pound fish and then this huge black shape just inhales it. Suddenly, your pole is doubled over and you’re down on your knees being mastered by this fish.”

Encounters with giant sea bass tend to make an impression. Douglas McCauley, a UC Santa Barbara marine biologist, grew up working on recreational fishing boats in the 90’s. “What haunts people is this memory of bringing in a five-or ten-pound fish and then this huge black shape just inhales it. Suddenly, your pole is doubled over and you’re down on your knees being mastered by this fish.”

Scuba divers have an entirely different perspective, likening the giants to huge underwater puppy dogs. The giant sea bass’s curious and fearless disposition astounds divers. “They’ll swim right up on you. They’ll follow you around. I’ve had them swim under my arms from behind. They’re super-curious and friendly,” said marine biologist Daniel Pondella of Occidental College, who’s studied them with Allen.

When Allen fell under the giant sea bass’s spell, he dedicated his career to studying them. He created the Giant Sea Bass Collective (GSBC), a group of scientists who have agreed to coordinate their research efforts. Cooperative scientific efforts like the GSBC are rare, and its members credit Allen with having the foresight to realize that such a group could help them avoid duplicating their efforts and therefore make quicker progress to understand giant sea bass biology.

“Larry was instrumental in igniting the giant sea bass research renaissance that we find ourselves in,” said Milton Love, a UC Santa Barbara marine biologist who’s worked with Allen on giant sea bass for many years.

Members of the GSBC are probing the movements of giant sea bass in several ways. Lowe of CSU Long Beach is fitting giants with acoustic tags to track them. The tags have revealed underwater journeys of up to 100 miles, dispelling the notion that these animals’ hugeness might make them sedentary. McCauley has also developed a kind of Facebook for giant sea bass– a web-based social network that allows divers to upload photos of giant sea bass they encounter. McCauley’s team uses software that reads the patterns unique to each fish’s flank to recognize individual fish and create a database.

In his own lab, Allen has revealed much of what scientists now know of the giant sea bass’s basic biology. No one knew how long they could live until 2012, when Allen paid $50 for the head of a 500-pound monster giant sea bass accidentally caught near Santa Barbara for $50. Then, he used power tools to extract the fish’s ear bone, or otolith, which has layers that can be used to age fish somewhat like the rings of a tree stump. The leviathan was 76 years old.

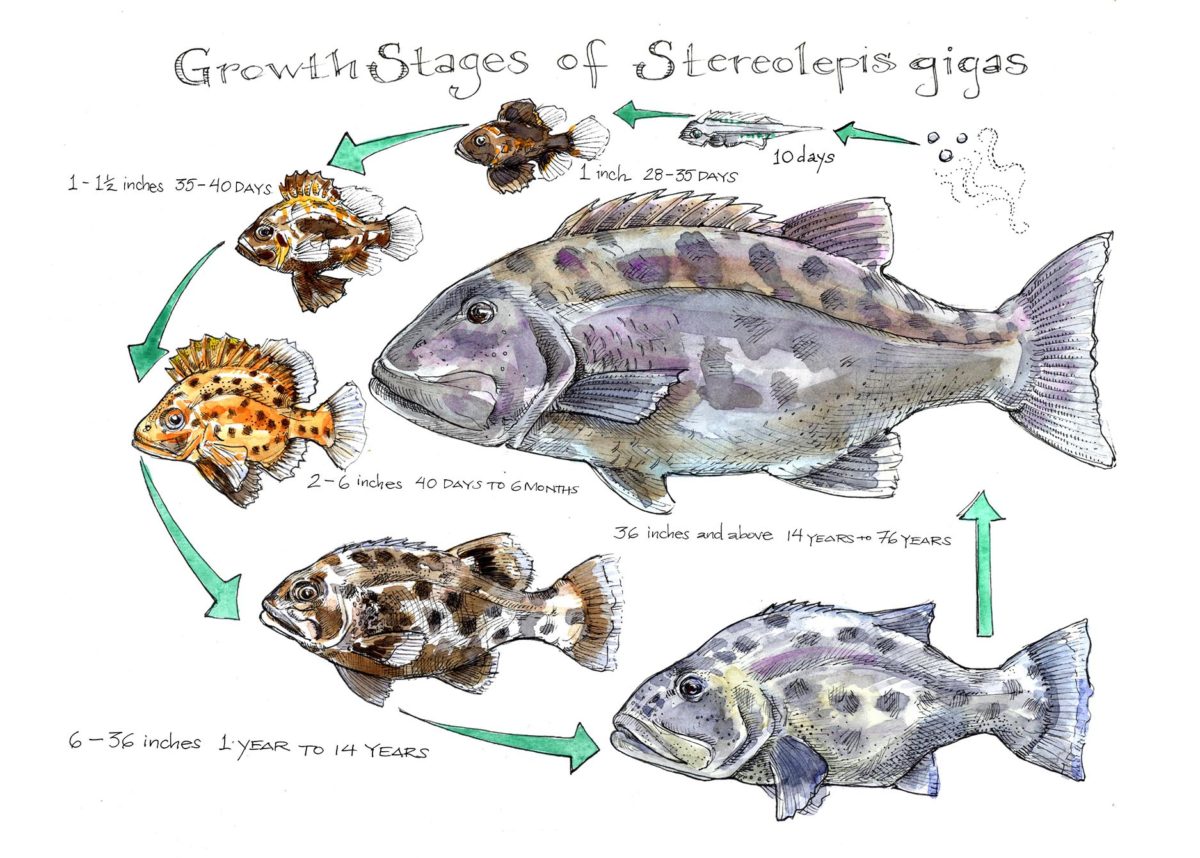

The giant sea bass begins its life as a speck floating in the ocean and goes through several distinct color changes along its path to adulthood. Illustration: Laurie Sawyer

Allen’s lab has also helped answer another big question in the field: how and where giant sea bass reproduce. Until recently, scientists had no idea where baby giant sea bass lived their early lives. Less than eight inches long and pumpkin orange with black spots, the juvenile giant sea bass is an altogether different creature than the huge, darkly colored adults of the species. In 2015, after five years of searching, Stephanie Benseman, a graduate student of Allen’s, and Michael Couffer, a diver and biologist, found the orange babies in the sandy expanse of shallow water just outside the breakers of Redondo Beach. The location worries the scientists: as climate change hastens beach erosion, places like Redondo are dredging for sand to replenish what the rising seas are rasping away.

“This is a habitat we didn’t know we needed to protect, and one with threats that could wipe out entire years of offspring,” said Benseman.

Recently, Allen has focused on another mystery of giant sea bass reproduction: the giants’ secret talent for singing. In 2014 and 2015, two of Allen’s graduate students recorded eerie rumbles at night around Catalina Island during the giant sea bass spawning season. When Allen played the recording on his laptop, the basso thrum was primordial.

By dissecting giant sea bass landed accidentally by commercial fishers, Allen had found that male giant sea bass have unique muscles in their rib cage. He suspected that these muscles might produce the underwater serenade by drumming on the fish’s swim bladder, helping them to woo females. If he could find the source of the underwater singing, he thought, he might be able to find more gatherings of giants, which could be used to designate new marine protected areas.

The problem was that the sea bass song had been recorded in total darkness. To prove the recordings weren’t from some other guttural resident of the kelp forest, Allen needed to catch a giant sea bass in the act of singing. This is what drove Allen to charter the “Reel Fun” and recruit her crew in 2017.

At a kelp bed the captain recommended, the “Reel Fun” shut off its motors and Allen’s nine anglers went to work. They quickly hooked up several giants, but the fish bolted for the safety of the kelp, easily snapping fishing line designed to withstand 100 pounds of force. “They’re like freight trains underwater,” Allen says. “If you’re hook and line fishing for them, the fish has a fighting chance.” Fourteen different fish snapped the fishing line or tangled their lines in the kelp.

The boat’s deck hand fought one giant for over an hour. He paced the perimeter of the boat, leaning back on the rod, hoping to muscle the fish out of the kelp forest. Finally, the fish tired and Allen’s crew carefully brought the 120-pound male aboard. Though still small for a giant sea bass, this was exactly the size fish Allen had been looking for. Any bigger and the 5,000-gallon tank he had prepared for the fish would be too small. He and the crew loaded the giant into a tank on board the “Reel Fun.” They landed two more fish late in the day, but only one of them was the right size; she joined her companion in the tank onboard.

Chris Pica (left), Captain of the “Reel Fun,” and deck hand Brian Pifer (right) help an ecstatic Larry Allen (center) lower one of the giants into a 300-gallon tank on board. Photo: Mike Couffer

Its mission accomplished, the “Reel Fun” motored back to the wharf. Back on land, the crew transferred its two captive fish to their new home in Allen’s lab: a nondescript warehouse building in the Port of Los Angeles. Today, the fish swim in their 5,000 gallon tank along with a third giant sea bass caught off San Diego. Allen and his students have named the trio Max, Squinty, and Taco.

Allen has become something like a record producer for these giant fish. For hours at a time, Allen dips an underwater microphone into their tank, hoping to catch Max, the male, in the act of singing his booming song. So far, Max isn’t performing.

But even as Max, Squinty, and Taco settle into their new home, Allen worries that their wild brothers and sisters are in peril as some fishers push California to repeal the ban on catching giant sea bass. These fishers say that the fish’s population is now healthy.

“They’re beyond abundant,” says Tim Athens, a commercial fisher since the ‘70s. “They have fully recovered. Honestly, they’re a nuisance.” Few things are more frustrating to fishers than hooking giant fish they’re not allowed to keep.

But Allen thinks that repealing the ban could cause dire consequences for the giants: “In these areas where fishermen the fishermen are encountering them a lot it’s important to think about what that amounts to—a lot could be 100. If you set the fleet loose on 100 fish, they’d be gone in a season,” he argues.

Allen and members of the GSBC are now working to strengthen protections for the fish’s home territories. Fishers are currently allowed to keep and sell one giant sea bass per fishing trip if they unintentionally catch the animal in nets targeting other species. McCauley has studied where and when commercial fishers are most likely to accidentally catch giants. Fishers bristle at the idea, but closing these hotspots to fishing during the summer, when the giant sea bass are gathering to spawn, could help curb the numbers killed by fishing.

Allen, Love, Pondella, and other GSBC researchers also argue that state regulators should stop allowing fishers to sell giant sea bass that they accidentally catch. They worry that this rule is harming the species. Commercial fishers sell an average of 100 accidentally caught fish every year. McCauley has calculated that this “incidental” giant sea bass fishery nets only $12,600 for California fishers each year. In contrast, he estimates, the bass’s annual value to scuba divers seeking an underwater encounter at roughly $2.3 million.

Giants also have immense value to the coastal ecosystems they inhabit, Allen says. Like lions, wolves and great white sharks, giant sea bass are top predators. Occupying their niche at the top of the food chain eases pressure on their prey’s food, including the kelp that forms the scaffolding of the entire ecosystem.

Giant sea bass aggregating in the kelp forests near Santa Catalina Island off the coast of Los Angeles, California. Photo: Mike Couffer

The return of giant sea bass has provided scientists with an opportunity to understand them better, but Allen is the first to admit that they still have a long way to go. “We know that there are more of them, but we don’t know how many there are supposed to be,” says Allen.

Allen thinks that hearing the song of the giant sea bass might be his best shot at answering that question. That’s what brings him into his lab on a recent Wednesday to greet his three captives. “Hello babies,” Allen says, as Taco, Squinty and Max swim up to greet Allen at the edge of their pool.

“I tell my students not to anthropomorphize, but I just love these guys,” says Allen, without taking his eyes off the trio. He pats them on their wet heads: “Food’s coming,” he promises.

As he feeds Max and his companions a meal of squid and sardines, Allen pauses: “I’ve been looking at some of these individual fish my whole professional life. That big one we aged was older than me,” he says, just as the sardine he’s holding above the water is hoovered up by a living piece of California’s wild heritage. So far, Max has remained silent. But Allen hopes that Max is just waiting for summer, the giant sea bass breeding season, to lay down a track. For Max, and for all of his wild cousins, Allen is willing to wait.

© 2018 Alex Fox / UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

Alex Fox

Author

B.A. (liberal arts) Sarah Lawrence College

Postbaccalaureate certificate (ecology and evolutionary biology) Columbia University

Internships: Santa Cruz Sentinel, San Jose Mercury News, Nature, the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, and Science

When I was eight, my former teacher asked me to channel my enthusiasm for biology into a presentation for her first-grade class about my favorite creatures—bats. With my copy of America’s Neighborhood Bats under one arm, I explained the differences between Megachiroptera and Microchiroptera to her squirming class of six-year-olds. As their eyes glazed over, it dawned on me that I had failed to consider my audience.

I later refined my skills as a communicator by writing short stories, press releases, and white papers. I learned that a well-crafted message can move people. I resolved to use my writing to connect others to the wonder and fragility of the natural world, by sharing the joy I feel watching bats cut silhouettes out of the night sky, and the heartbreak of naming the species and habitats we’ve lost.

Laurie Mahan Sawyer

Illustrator

B.F.A. (illustration) Art Center College of Design

Internship: NOAA/ Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary

Inspiration of the natural world has led me to the drawing board. Years spent in and around, up and down the canyons and coast of California have created a backlog of endless subject matter. I hope to make and share artwork that informs and feeds curiosity of this vast flora and fauna, terrestrial and aquatic.

Available as an illustrator, designer or hunter gatherer for your floral fantasies.

Your illustrator, Laurie Sawyer is amazing, her colors bring the fish alive. I found the commentary very informative and my eyes did not glaze over.

Great article with Dr. Allen and the illustrations are amazing.

The article is in need of some editing but otherwise informative.