Living with noise

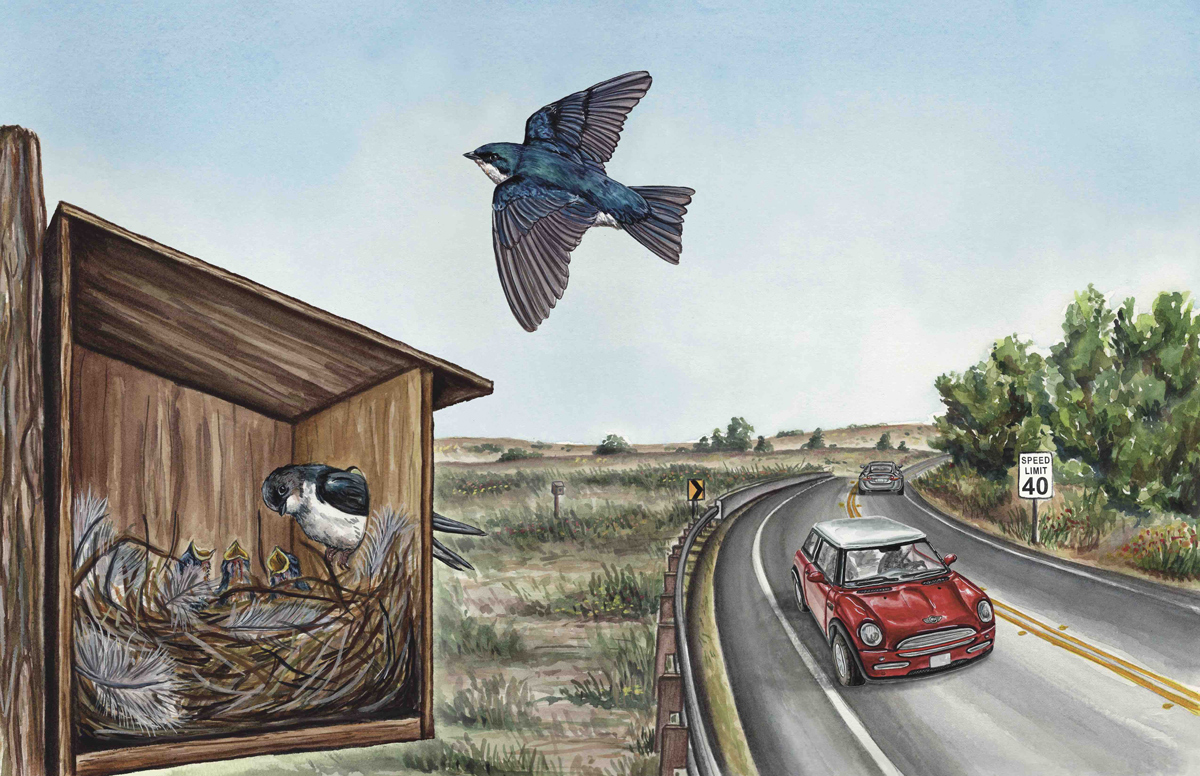

Wild animals suffer when they can’t escape traffic noise, Priyanka Runwal reports. Illustration by Holly Sullivan.

Illustration: Holly Sullivan

Crouched in a field of grass, Allison Injaian sat still. “If you move, you’ll look like a big scary predator,” she said, recalling the moment three years later.

Injaian, a behavioral ecologist then at UC Davis, tried to become invisible; her dull grey fleece jacket helped her blend into the pale February morning. Otherwise, the birds she hoped to observe might avoid the area.

Sudden bursts of high-pitched chirps burbled in the distance. Injaian’s face lit up. She reached for the binoculars strapped around her neck and pointed them in the direction of the distinct sound.

As she watched, the open field came to life. Injaian spotted white and iridescent blue bodies perform aerial acrobatics. With quick swoops and sharp turns, tiny birds, the size of Injaian’s palm, pursued flying insect treats. The tree swallows that Injaian had been waiting for had arrived from their annual spring migration.

But the chirps weren’t the only sounds familiar to Injaian. She could hear another faint sound in the background: cars and trucks driving through a two-lane highway half a mile away. The cars reminded her that traffic noise is almost impossible to escape – even in the rural setting of Putah Creek South Fork Preserve, four miles from the city of Davis, California. She hoped to learn how the constant din of modern life affected the tree swallows whose arrival she had just witnessed.

“If we can understand how noise specifically affects tree swallows, then it can give us a better idea of how it might affect other such birds,” she said.

83 percent of land in the U.S. is within a half mile of a road. Researchers estimate that many U.S. national parks are twice as loud as they would be in the absence of manmade noise. While urban wildlife like pigeons are getting used to this noise, Injaian wants to understand how rural species cope.

Scientists have been studying road impacts on animals since the 1930s. They started by looking at how roads break up landscapes and harm animals by blocking their movements and allowing free access to loggers and poachers. Only in the past decade have scientists shifted focus to the noise aspect of roads.

Birds are sensitive to noise. Traffic sounds interfere with the calls they use to communicate with each other. A study showed that highway noise dissuaded migrating songbirds from stopping at their regular resting site near Boise, Idaho. In Wyoming, this noise discouraged endangered sage grouse from visiting their courtship sites, where males customarily strut and sing. Some birds have adapted: great tits sing at higher frequencies to make themselves heard over traffic noise. European robins have become more vocal during the night, when it’s quiet and roads are less busy. “You are basically removing one of the channels that animals use to communicate,” said Gail Patricelli at UC, Davis, who studies traffic noise impacts on birds.

But what about birds like tree swallows that aren’t as chatty and vocal? Would traffic noise impact them in a different way, for instance, by altering their nesting habits? “We need to understand the full impacts noise could have on birds….besides communication,” Injaian said.

It was her quest to answer that question which brought Injaian to the grassy hiding spot on that cold morning.

Tree swallows – the ‘model’ species

As a master’s student in ecology and evolutionary biology, Injaian had read about Patricelli’s work identifying manmade noise as a threat to sage grouse. She was intrigued by the pervasiveness of noise in the environment and the conservation potential of Patricelli’s work.

“As a lab we were starting to get more interested in this issue of noise,” Patricelli said. After learning that traffic noise affected sage grouse behavior, she wanted to know how this disturbance might affect other species.

Injaian came to Patricelli’s lab in 2015, just as the lab was thinking of new ways to study traffic noise impacts on birds. While working with tree swallows on another lab project, Injaian figured how easy they were to handle and work with. She also learned that these birds readily nested in bird houses, and could be easily tracked.

If she could play recordings of traffic noise to these birds and see if they behaved differently, she’d learn what noise was doing to them. Realizing that learnings from tree swallows could apply to other wild birds too, Injaian embarked on this research project.

“It was exciting and terrifying at the same time,” she said.

Laying the foundation

Each February, tree swallows return from their winter homes to build nests in Putah Creek Riparian Reserve and South Fork Preserve, both within 15 minutes’ drive from the university town of Davis.

They build their nests in wooden boxes, called nest boxes, mounted on five-feet-tall poles and scattered across the open landscape. Each nest box has a three-inch hole that birds use to go in and out. There’s a flap door that scientists use to spy on birds inside the box. They can see if the birds are nesting, if they’ve laid eggs, or if the hatchlings are doing well.

Allison Injaian standing next to a nest box used by tree swallows at the Putah Creek Riparian Reserve, near Davis, California. Image Credit: Gail Patricelli.

In 2016, Injaian set out 35 nest boxes in the study sites. She exposed 19 of them to noise while keeping the area near the others silent. She played six-hour-long traffic noise recordings, every morning, from February until April. That’s the period when swallows are most active: they’re foraging, visiting nest boxes, and deciding which one to nest in.

She wanted to understand if birds would abandon noisier nest boxes. And if some did choose to nest in the noisy spots, she wondered if that meant bad news for the next generation.

Noisy experiment

Before the speakers could blast traffic noise, Injaian measured the quietness of the natural surroundings. Her field sites were as silent as a library on that cold February morning.

This gave her an idea of sound levels that tree swallows experienced on an everyday basis. It also helped her understand how much louder it would get once the recordings played.

The dishwasher volume is what rural birds may experience if traffic became more constant in the future.

The clock struck 8:00. The speakers fired up automatically. They played sounds of moving traffic that were as loud as a dishwasher.

According to Andrew Horn, an evolutionary biologist at Dalhousie University in Canada, who was not involved in the study, this noise exposure seemed realistic. The dishwasher volume is what rural birds may experience if traffic became more constant in the future.

Crouched at a distance, Injaian was observing one of the noisy nest boxes. She set her stopwatch for 20 minutes and observed if the birds approached this nest box. If tree swallows hovered within seven feet, it indicated to her that they were potential clients interested in the house. If this interest persisted for at least two days, it was a sign that the house was sold.

Once sold, the birds guarded their homes and began renovating the interiors. They used grass blades, moss and discarded feathers to make a cozy home before laying eggs.

Over the next two months, Injaian maintained a catalog of dates for when each house got occupied and who the residents were. After April, when the birds had settled and started a family, she kept track of their eggs and newborn babies.

Delayed settlement, fewer eggs and babies

At the noisier nest boxes, Injaian recalled spending lots of boring mornings, waiting around, with nothing to do. The birds didn’t warm up to the loud neighborhoods as easily.

The quieter areas, on the other hand, were more active. Tree swallows displayed more affinity to the nest boxes there.

Her research showed that tree swallows, on average, took 25 days longer to settle in areas that sounded twice as loud to humans. “This indicates that noise is an important part of habitat selection,” said John Swaddle, behavioral ecologist at College of William and Mary, Virginia, who wasn’t involved in the research.

For females in noisy territories, this meant that their egg-laying dates got pushed further. And even though traffic playback halted before egg-laying, females in the noisy spots laid 0.58 fewer eggs. Also, the surviving chicks weighed less and had shorter wings. “What we don’t know is if the nestlings actually survive till adulthood,” Injaian pointed out. “It’s very hard to track them long-term.”

Patricelli, who supervised this research, was surprised that mere two-month exposures could impact the birds’ breeding biology. What would happen if swallows were subjected to noise for extended periods still remains to be seen.

Robert Dooling, professor of acoustic communication at the University of Maryland, who wasn’t involved in the research, believes that the noise impacts Injaian observed were small. “But that doesn’t mean the effects are not important,” Dooling said.

“It’s a little bit like global warming,” he stressed. “It’s not a crisis situation at the moment…but things might add up, reach a threshold, and then you have a catastrophe of species disappearing or moving out.”

Although Patricelli agrees about the small effects, she hopes studies like these will put traffic noise on the radar of conservation organizations. But Andrea Jones, bird conservation officer at Audubon California, said that managing roads to improve nesting in common and abundant birds is challenging. “Unless it was an endangered species, it would be very hard to manage roads,” she said.

For wildlife, endangered or not, tackling noise may require innovative solutions, such as improved road designs, smoother road surfaces, or quieter vehicles. “Can we engineer our built environment to cause less impacts for wildlife? That is the question for the future,” Swaddle said.

© 2019 Priyanka Runwal / UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

Priyanka Runwal

Author

B.S. (Environmental Science) University of East Anglia, U.K.

M.S. (Biodiversity Conservation) University of Oxford, U.K.

Internships: Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, Monterey Herald, San Jose Mercury News, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

It had been a typical day in the arid grasslands of Kachchh. As a field ecologist, I had spent the afternoon counting plants and collecting leaves in our 40-square-mile study site in the Indian state of Gujarat. I crouched to record my last entry for the day—and realized I wasn’t alone. A pair of wolves had been watching my every move.

The wolves sprang toward me as I took off running. They chased me for a quarter of a mile before I finally made it to the safety of my pickup truck. It was an alarming reminder that the drylands I studied are not the barren, lifeless wastelands that most people assume them to be.

Deserts are teeming with life, though it is often camouflaged. Now, as a science writer, I am determined to get people curious about the natural world—even in seemingly desolate environments.

Holly Sullivan

Illustrator

B.S. (Animal Science) University of Massachusetts Amherst

Internship: Harvard University (Cambridge, Massachusetts)

Being able to incorporate animals into a career filled with art and learning are my main goals in life. As a science illustrator, I aim to educate as well as invoke interest and appreciation for science and the natural world through my artwork. I specialize in projects pertaining to zoology, evolutionary biology, natural science, veterinary medicine, and animal science.

In 2017, I graduated from the University of Massachusetts Amherst with a B.S. in Animal Science. Upon completion of the California State University Monterey Bay Science Illustration Graduate Program, I will be starting a full-time position as a Graphics Assistant and Science Illustrator at Harvard University. I’m excited for all the wonderful opportunities this position has to offer. I also plan to continue to do freelance work along with this job.

When not working in my studio, I can be found wherever animals are. Whether it be out hiking and hoping to catch a glimpse of the elusive local wildlife, wrangling livestock, or spending time with my studio sidekick, Walden the dog.