Reinventing California’s swordfish fishery

Annie Roth examines a new invention that could keep the California swordfish fishery afloat. Illustrated by Allison Fitzmorris.

Illustration: Allison Fitzmorris

In a tiny office building next to a bait shop in Oceanside, California, Chugey Sepulveda and Scott Aalbers sit behind desks covered in mounds of fishing line and research papers. Clipped to a whiteboard above Sepulveda’s desk is a photo of Sepulveda and Aalbers holding up a 200-pound swordfish. This photo isn’t a memento of vacations past; it’s a tribute to their accomplishments. Sepulveda and Aalbers are both fishermen-turned-fishery scientists, and for the last 14 years, the pair has been looking for a better way to catch swordfish.

California’s commercial fishermen are in desperate need of a new swordfishing method. In September 2018, California Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill that will ban the most widely used method for catching swordfish from commercial use by 2022. This method, known as drift gillnetting, is one of only two legal ways commercial fishermen can catch swordfish in California.

Harpooning — the only legal alternative to drift gilnetting – is expensive and inefficient by comparison. So gillnets have long been the fishing gear of choice for the vast majority of California’s swordfish fishermen. Although these nets are designed to catch fish, they often snare marine mammals and sea turtles as well. An estimated 103 sea turtles, 1,841 seals and sea lions and 4,5423 dolphins have drowned in drift gillnets since 1990. But this type of fishing will soon be illegal within three nautical miles of the coast of California. And in August 2018, three U.S. senators introduced bills that would extend the ban to 200 nautical miles from shore and ban drift gillnets from national waters.

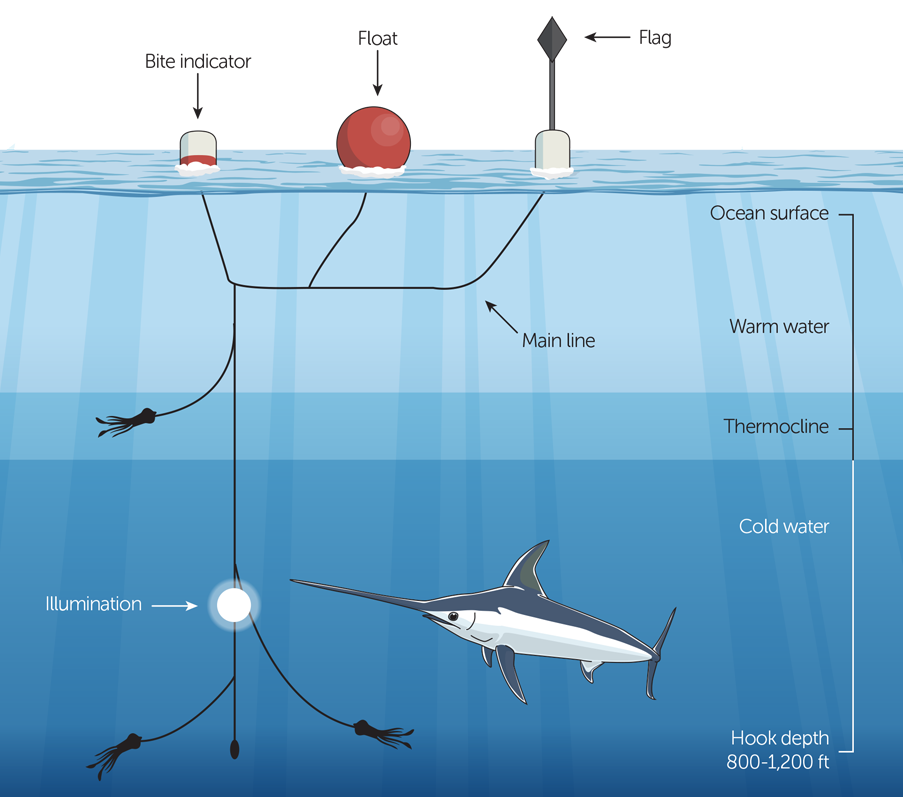

California swordfishers argue that without gillnets, the domestic supply of swordfish will plummet, increasing demand for unsustainably caught swordfish from overseas. Now, scientists, fishermen, and environmentalists are working together to develop a new type of fishing gear that is both viable for commercial use and environmentally friendly. Chugey and Sepulveda hope this new gear, called “deep-set buoy gear,” will increase the supply of domestic swordfish and revitalize California’s dwindling swordfish fishery.

More fish, more problems

Prior to 1980, the only legal way to catch swordfish off California’s coast was with a harpoon or a rod and reel. These highly selective methods, which pose no threat to marine mammals, supported a small but healthy fishery until 1980, when drift gillnets were legalized for commercial swordfishing in California.

Drift gillnets are mile-long transparent nets that hang vertically in the water column. These nets, which can be as long as the Golden Gate Bridge and as tall as a giant sequoia, are typically set near the surface and left in the water overnight. In addition to swordfish, drift gillnets catch thresher sharks, opah, and tuna. Fishermen can catch significantly more swordfish per trip with a gillnet than they can with a harpoon, and so quickly became the primary method for catching swordfish after they were legalized.

Unfortunately, commercially desirable species comprise less constitute less than half of every drift gillnet haul. Other fish, such as striped marlins and mola molas, comprise the majority of this fisheries’ unintended catch, or bycatch. Marine mammals and sea turtles are often caught as well, and are particularly vulnerable to entanglement in gillnets, which block them from surfacing to breathe.

-

A dead California sea lion caught in gillnet near California’s Channel Islands. Photo by Howard Hall 1983

-

A grey whale washed ashore in Southern California after drowning in a gillnet. Photo by Howard Hall 1983

-

A mola mola, also known as a sunfish, entangled in a gillnet near California’s Channel Islands. Photo by Paul Nicklen 2018

-

A swordfish caught in a gillnet off the coast of Southern California. Swordfish typically make up less than a quarter of what gillnet fishermen catch in California. Photo by Paul Nicklen 2018

-

A blue shark entangled in gillnet off the coast of Southern California. Photo by Howard Hall 1983

-

Photographer Brock Cahill photographing an entangled swordfish off the coast of Southern California. Photo by Paul Nicklen 2018

Because drift gillnets are typically left in the water overnight, animals who become entangled in them can be injured or killed by the time the gear is retrieved. Between 1985 and 2001, the National Marine Fishery Service, now known as NOAA Fisheries, restricted the use of drift gillnets in several fishing grounds. The most severe restriction was the creation of the Pacific Leatherback Conservation Area, which prohibited the use of gillnets in 213,000 square miles of prime fishing ground off the West Coast for three months of the year.

The National Marine Fishery Service hoped these restrictions would reduce the fisheries’ impact on endangered species, and for the most part, they did. However, they also prevented fishermen from catching the amount of fish needed to turn a profit. These regulations cut catch rates in half and discouraged fishermen from investing in permits. By 2004, the swordfish fishery was all but abandoned. The California swordfish fisherman had become an endangered species.

Fishing for solutions

While all this was happening, Sepulveda was earning his doctorate in marine biology from Scripps Institution of Oceanography. During his doctoral studies, Sepulveda worked closely with commercial fishermen in Southern California and saw how the decline of the swordfish fishery was impacting the local fishing community. As a dedicated angler and California native, Sepulveda was sympathetic to the plight of California’s swordfishers and became determined to make a difference. Sepulveda calls himself a fisherman first and a scientist second.

Like many fishermen, Sepulveda’s professional attire consists of a Hawaiian shirt and cargo shorts. In 2004, Sepulveda finished school and began working for the Pfleger Institute of Environmental Research (PIER), a non-profit dedicated to improving the sustainability of fisheries through applied research and education. When Sepulveda joined PIER’s research team, he re-directed its focus towards finding a sustainable way for fishermen to catch swordfish in California.

Sepulveda’s first project at PIER involved tracking the movements of swordfish off the Southern California Bight – the curved coastline of southern California that extends from Point Conception to San Diego. Although fishermen like Sepulveda had been catching swordfish in southern California waters for more than a century, very little was known about the fine-scale movements of these fish and less about their interactions with other species.

The team attached satellite tags to nine swordfish and observed each animal’s movements for up to three months. The data collected by these tags suggested swordfish spend their mornings feeding on squid and baitfish below the thermocline, a cold and desolate region of the ocean located hundreds of feet below the surface.This area is rarely visited by marine mammals and sea turtles, which makes it the perfect place to target swordfish. Unfortunately, neither harpoons nor gillnets can reach swordfish at this depth, so the team had to find something that could.

The missing piece of the puzzle

Meanwhile, 2000 miles away, a commercial swordfisher named Tim Palmer had already developed what would become the missing piece of PIER’s puzzle. In 2001, fishery managers in Florida banned the use of longlines in the Florida Strait, a shallow channel that stretches from southeastern Florida to Cuba. Longlines consist of hundreds of baited hooks hanging from a piece of fishing line that is suspended horizontally in the water column. Like gillnets, longlines are unselective and pose a threat to endangered species – hence Florida’s ban.

The Florida Strait is teeming with hefty swordfish and this ban was preventing Palmer from catching them. But instead of getting angry, Palmer got creative. Palmer needed gear that could catch swordfish without harming other species, so he made one. His creation, known as buoy gear, works a lot like a fishing pole. The gear consists of one or two hooks attached to single fishing line suspended by a buoy. Fishermen place 10 to 20 of these buoys in a straight line. When a swordfish gets caught by a piece of buoy gear, it will instinctively swim towards the seafloor. This escape attempt pulls the buoy out of alignment, alerting the fisherman that he has a fish on the line. Fishermen keep their boats close to the buoys so they can retrieve their catch as soon as it’s hooked.

Aficionados such as Travis Moore, a marine biologist and recreational swordfish angler, say that swordfish caught this way are fresher, with firmer and more flavorful meat, than are swordfish caught on long lines and gillnets. Moore was one of the first people use this new fishing gear.

When longlines were banned from the Florida Strait, the local swordfish supply began to plummet. By 2006, local swordfish had all but disappeared from Florida’s fish markets. In response to this crisis, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) authorized the use of buoy gear for commercial swordfishing in Florida waters.

“Using this gear just blew my mind. Your bycatch levels are almost zero,” says Moore.

Because this gear was largely untested, the National Marine Fisheries Service was unsure if widespread use of this gear posed a threat to any endangered species. To find out, the agency put observers on dozens of boats using buoy gear. Moore was one of these observers. When he started observing the buoy gear fishery in 2009, he was blown away by its selectivity. “Using this gear just blew my mind. Your bycatch levels are almost zero,” says Moore. Only 8 percent of the fish caught on buoy gear in Florida between 2007-2011 was bycatch, and 93 percent of that bycatch was released unharmed.

The future of swordfishing

Currently, less than 10 percent of the swordfish landed in Florida is caught on buoy gear, but Moore thinks that may soon change. “I’m seeing a lot of guys that used to commercial longline switch over to buoy gear. Captains are starting to realize they can make money off this with less effort,” said Moore. The authorization of buoy gear also brought a lot of new participants into the fishery, most of which own small sport fishing boats. Because buoy gear costs far less than a longline and doesn’t require a large boat or expensive machinery to operate, it’s a viable option for fishermen with boats of all sizes.

After seeing the positive impact buoy gear had on Florida’s swordfish fishery, the National Marine Fisheries Service asked Moore to help export the technology overseas. Moore spent several years in Turkey and Morocco, building buoy gear and teaching local fishermen how to use it. “One of the goals of fishery science is to improve the lives of fishermen,” said Moore. “Seeing these guys being able to continue fishing, enjoy fishing, make money, and feed their families while using a resource sustainably was a pretty cool experience.”

Bringing buoys to California

By 2009, every swordfish fisherman had heard about buoy gear — including Sepulveda. Even though the gear was designed to work in the Florida Straits, where swordfish congregate in the shallows, Sepulveda believed the gear could be modified to catch swordfish at depth. Sepulveda theorized that this could be achieved by extending the line and adding additional floats and weights. After a few months of trial and error, Sepulveda had a prototype that was ready for testing. In the summer of 2011, he and Aalbers decided to test this modified buoy gear, which they called “deep-set buoy gear.”

The sun was well below the horizon when Sepulveda, Albers and a deckhand boarded their research vessel and headed out to sea. In the darkness of the early morning, the team gathered on the deck and prepared their gear for launch. Ten buoys, each equipped with a weighted line and two baited hooks, were tossed into the water. The crew took turns watching the buoys through binoculars, ready to respond at the first sign of movement. Hours passed without so much as a nibble. The crew waited and waited, but the swordfish just weren’t biting. “No one was sure it was going to work,” recalls Sepulveda.

Finally, when the sun began to set, the crew decided to pack it in. But just as they were preparing to haul their gear back on deck, one of the buoys began whirling violently across the surface of the water. The team sprung into action. Aalbers steered the boat towards the buoy while Sepulveda prepared to pull it out of the water. When the buoy was within reach, Sepulveda hoisted it aboard and affixed its line to a motorized reel. The crew starred anxiously at the surface of the water as their catch was dragged from the abyss. Suddenly, their catch surfaced: a 200-pound swordfish, its silvery scales shining in the sunlight. The crew pulled it aboard; it landed on deck with a massive thump.

The crew was ecstatic, especially Sepulveda. The massive swordfish flopping by his feet was living proof that his gear worked. For the first time in many years, Sepulveda felt optimistic about the future of California’s swordfish fishery.

Before tagging and releasing their fish, Sepulveda and Aalbers knelt beside it while their deckhand took a photo. Sepulveda keeps that photo above his desk as a reminder of how far he has come. “That was really just the beginning. We’ve caught so many swordfish using the gear since then, and so have a lot of fishermen. We’re really in a different place now than we were then,” he says.

Testing the waters

In order to get this gear into the hands of California’s commercial fishermen, Sepulveda had to convince the body that regulates California fisheries — Pacific Fishery Management Council — that deep-set buoy gear could be used without harming endangered species. Sepulveda knew he was going to need a mountain of irrefutable evidence to convince the council, so he began conducting gear trials.

At first, Sepulveda and Aalbers were the only fishermen authorized to test this gear. But as public interest grew, commercial fishermen began lobbying for permits to use it. In 2015, the council began issuing “experimental fishing permits” to local swordfishers who wanted to participate in PIER’s buoy gear trials.

These permits allowed fishermen to use buoy gear for one season as long as they allowed a fishery observer on board during all their commercial fishing trips. Between 2011 and early 2017, California fishermen caught hundreds of swordfish using deep-set buoy gear without killing or injuring a single endangered animal. A whopping 98 percent of the catch was marketable, and 100 percent of the bycatch was released alive. “It’s very exciting,” says Chris Fanning, a fishery policy analyst at NOAA Fisheries in Long Beach.

According to Fanning, only two marine mammals were caught during these trials, and in both cases, the animal was released alive and unharmed. Fanning is not the only one who is excited by the success of these trials. Fishermen are lining up for permits to use this gear; Fanning’s office, which makes the final decisions about who can use the gear, received over 60 applications in 2017.

The permits only allow fishermen to deploy 10 buoys at a time. Fortunately, the high value of the fish makes up for the limited catch. Swordfish caught on deep-set buoy gear sell for roughly $8.75/lb. Swordfish caught with a drift gillnet are only worth around $4.34/lb.

No more nets

Environmental groups including Oceana and Sea Shepherd have long campaigned for a ban on drift gillnets in California. Over the last two decades, environmental groups have introduced two different pieces of legislation to further restrict the use of drift gill nets, but neither passed due to a lack of public support. But now, thanks to the development of deep-set buoy gear, their cause has more support than ever. According to a poll commissioned by The Pew Charitable Trusts in 2016, more than 75 percent of Californians supported ending the use of drift gillnets to catch swordfish, with 87 percent of those surveyed agreeing that fishermen should use less harmful gear.

“This isn’t about the fleet being a bunch of evildoers, these are good people fishing with bad gear,” says Paul Shively, who directs the Pew Charitable Trusts’ work on ocean conservation in the Pacific. Pew helped fund the development of deep-set buoy gear and continues to lobby for its authorization.

“We don’t want to stop swordfishing on the West Coast, we want to see a better way to catch them,” Shively says. “We know there’s a better way to catch fish off the West coast, the decision makers know there’s a better way, and they know the public supports a transition away from drift gillnets.”

Senator Ben Allen, who represents California’s 26th district, introduced the bill that ultimately put this transition in motion. The bill, known as Senate Bill 1017, was signed into law on September 27, 2018. It will phase out the use of drift gillnets over a four-year period, following the establishment of a buyback program for drift gillnets permits and gear. This program, funded by public and private entities, will offer drift gillnet fishermen $10,000 for their permits and $100,000 for their gillnets.

Unlike past anti-gill net legislation, this bill had massive public support. More than 100,000 people, for instance, signed an online petition calling for the passage of S.B. 2017. The petition was released by Paul Nicklen, a National Geographic photographer and founder of the non-profit Sea Legacy, who told his 4.6 million followers in an Instagram post, “We must end this destructive practice immediately.”

But many fishermen don’t want to give up gillnetting, including Kelly Fukushima. Fukushima, who has been catching swordfish off the coast of San Diego for more than 20 years, doesn’t think the development of deep-set buoy gear should be used to justify a drift gillnet ban.

“Closing the drift gillnet fishery would be detrimental not only to local fishermen and the fishing industry on the West Coast but also to the U.S. supply of domestic swordfish,” said Fukushima.

California’s drift gillnet fishery is the largest producer of domestically caught swordfish on the West Coast of the United States. Despite having a healthy swordfish stock within its waters, the vast majority of the swordfish consumed on the West Coast is caught overseas, usually by a gillnet or longline.

Foreign swordfishing fleets kill far more endangered marine mammals and sea turtles than California’s drift gillnet fishery. For example, Canada’s swordfish fishery kills an estimated 1,200 endangered sea turtles every year. Estimates suggest California’s swordfish fishery kills less than five endangered sea turtles each year. Fukushima believes the upcoming ban on the use of drift gillnets in California waters won’t solve the fisheries’ bycatch problem, it will export it.

At 44 years old, Fukushima is young for a fisherman. Unlike many of his older, more salty peers, Fukushima is open to new ideas. Fukushima was one of the first fishermen to test deep-set buoy gear in PIER’s trials, and he supports its authorization. However, Fukushima sees deep-set buoy gear as nothing more than a way to increase his fishing effort.

“By no means is buoy gear ever going to replace drift gillnets,” said Fukushima. “I think its intended use is to allow fishing in different [weather] conditions, not to replace anything.”

Tides are turning

The Pacific Fishery Management Council, whose members include fishermen, industry stakeholders and federal and state officials from the National Marine Fisheries Service, will ultimately decide if deep-set buoy gear is legalized in California. The council is expected to make a decision by 2020; Sepulveda and Albers say they are confident the council will authorize their gear.

Whether deep-set buoy gear is used alongside or in place of drift gillnets is irrelevant to Sepulveda. Sepulveda developed this gear for one simple reason: to ensure that the swordfish fishermen in his community can earn a decent living doing what they love. “Positive interactions with fishermen occur on a daily basis and they’re what really drives us to continue to do the work we do,” said Sepulveda.

Sepulveda recently began working on another alternative fishing gear, which he calls “linked deep-set buoy gear.” Sepulveda hopes this new gear, which consists of several pieces of buoy gear connected by a rope, will allow fishermen to catch swordfish at depth with the same efficiency as a gillnet set on the surface.

Sepulveda has already done a great deal to ensure the survival of California’s swordfish fishery, but his work is far from over. “The goal 14 years ago, and still now is to try to build clean, sustainable, domestic fisheries and provide more opportunity for domestic fishermen,” said Sepulveda. © 2018 Annie Roth / UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

Annie Roth

Author

B.S. (marine biology) University of California, Santa Cruz

Internships: National Geographic, Inside Science and the Monterey Herald.

When I wasn’t buried under a mountain of National Geographic magazines as a kid, I was parked in front of a television watching Steve Irwin’s Crocodile Hunter. Wildlife documentaries and magazines inspired my passion to save the natural world, despite my upbringing among the high-rise buildings of New York City. When I graduated from college, I tried every job whose description included the word “conservation.”

After two years of monitoring king salmon populations in Monterey Bay, I felt like I’d eaten more fish than I’d saved. By pursuing a career in scientific communication, I hope to make a bigger impact and inspire millions to support conservation. Steve Irwin taught me that if you want to protect wildlife, you must make people fall in love with it. I’m living proof that this can work.

Allison Fitzmorris

Illustrator

B.A. (philosophy) Fordham University, 2013

Internship: National Outdoor Leadership School (Lander, WY)

As a little girl, I wished that I could travel back in time and become a naturalist. I dreamed of discovering strange creatures and exotic plants while trekking through unexplored jungles and unmapped peaks. I would draw them and name them and then send my journals back home so everyone could see what I saw, so everyone could see how beautiful and wild the world is. How lucky I am to have discovered the field of scientific illustration! My childhood wishes have been fulfilled: I can share all the amazing and wonderful things I see with the rest of the world and strive to impart the of the awe I feel in nature with my artwork.

This summer, I will be working in Yosemite National Park with the US Forest Service, collecting data about pine martens and fishers. My field sketches and illustrations will be used to promote this research and generate public interest. In the fall I will move to Lander, WY to illustrate a book for NOLS, the National Outdoor Leadership School. I’m grateful for these opportunities to combine my love of the outdoors with my passion for art and I’m excited to see where they will lead me.

Excellent article and illustration.