The Science and Art of Saving Joshua Trees

Joshua trees are stressed under environmental and human threats. Roxanne Hoorn reports on one artist and scientist’s fight to save them. Illustrated by Audrey Sauble and Emily Mitchell.

Illustration: Audrey Sauble

Walking into Juniper Harrower’s sun-drenched office, it’s hard to tell if you’ve just entered an art studio, botany lab or natural history museum.

The tables are covered with oozing acrylic paints and vast arrays of color swatches. The shelves teem with a collection of twigs, spines, cones and mysterious liquids in various shapes of corked bottles. In the middle of the office, a series of smooth branches and roots are suspended in mid-air.

A Joshua tree seed pod–a tan palm-sized husk–sits in a Petri dish. Its rows of smooth black seeds the size of pinky nails spill out onto the table.

Harrower, a scientist and artist, uses this colorful space to translate her ecological research on Joshua trees into art.

Harrower has dedicated her life’s work to the Joshua tree, a western icon that she grew up with in the Mojave Desert of southern California. She explores how the many sides of herself as a scientist, artist and activist impact the conservation of this species. She may not speak for the trees, but she has spoken with them. With microscopes, paint brushes, and modeling clay alike, she explores their inner world and asks questions of them that no one else has thought to.

Harrower’s research has helped show that the millions of Joshua trees that currently sprawl across the Mojave Desert of southern California are in peril. Rapidly expanding development of homes and massive solar farms threaten these thriving populations of Joshua trees. And Harrower has found that climate change threatens these plants’ fragile relationships with their pollinators.

Now, Harrower’s research and others’ has led to a petition to list Joshua trees under the California Endangered Species Act due to threats from climate change, which would make the removal of trees illegal without extremely expensive state authorization. Harrower’s research influences policy through practical findings, while her art draws people into her science and the inner world of this threatened species.

“I found the sciences are really highly effective for legal situations when you need evidence,” like petitions to protect species, says Harrower. “But I work with my art to inspire people to show up for things and then start working with these systems themselves.”

Joshua Tree Background

Joshua trees are gangly desert icons. Their fibrous stalks sprout arms that shoot awkwardly in all directions, sprouting spiky plumes of leaves at their tips. The endearing plants resemble mutant cheerleaders lifting their pointed pompoms in a frozen flash mob against the desert landscape.

Though commonly called “trees,” the plants are actually part of the agave family and thus more akin to grasses and palms. There are two species of Joshua trees that occupy overlapping but varied ranges, bear different fruit and host unique pollinators. The western Joshua tree (Yucca brevifolia), the subject of Harrower’s research, is taller and more ‘tree-like’ in appearance than its shrubby eastern relative.

Joshua trees have lived in southwestern deserts for the past 2.5 million years. But Harrower and other scientists are now worried for their future as the climate changes. In 2019, scientists warned that up to 90 percent of Joshua trees in Joshua Tree National Park could disappear by the end of the century.

These sensitive plants only grow in a boomerang-shaped range across portions of the Mojave Desert in the southwestern U.S. But in some low-lying parts of their range, higher temperatures are wilting the plants, causing their gnarled branches to droop to the ground and eventually sever from the tree. It’s as if the plant itself is melting like the clocks in the famous Salvador Dali surrealist painting, Persistence of Memory. In some of these parched and sweltering areas of the park, trees have stopped sprouting, meaning the Joshua trees there now could be the last generation.

While the trees inside the park are falling victim to climate change, those outside its bounds are often ripped from the ground for development. New home construction poses the main threat to the Joshua tree habitat immediately outside the park. Moving north in the tree’s range, large-scale developments for solar farms and warehouse distribution centers are expanding, taking up swaths of land with high densities of Joshua trees.

On top of it all, wildfires burned 259,057 acres of western Joshua tree habitat in the last 40 years, scorching many trees already plagued by rising heat and drought.

This triple threat of climate, fire and development is drastically shrinking Joshua trees’ range. Brendan Cummings, lawyer and the director of the Center for Biological Diversity, fears that without increased protections, Joshua trees may face the same fate as another threatened desert dweller, the desert tortoise. Cummings says the burrowing reptile is completely gone from parts of its home range due to habitat destruction. “You just eat away at the habitat of a species bit by bit,” says Cummings. “Once you’ve done that enough it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy” and a species disappears. He fears Joshua trees may be on the same trajectory.

A Joshua tree stands on the edge of a plot of land for sale in San Bernardino County, CA. Photo by Roxanne Hoorn.

Art and Science

Art has always gone hand-in-hand with science for Harrower, who first fell in love with nature while painting plants as a kid. However, she never dreamed of pursuing art when it came time to pick a college major.

“I’m a first-generation college student from a rural community. I wasn’t going to study art,” she says. “That just seemed like something rich people did.”

After graduation, Harrower bounced between jobs in science and art. She worked as an art teacher in Argentina and researched the cloud forests of Monteverde, Costa Rica. While working toward her doctorate in environmental sciences at the University of California Santa Cruz, she was finally able to marry the worlds of science and art in her research. She decided that her muse would be the plight of the pseudo-trees she grew up with in the Mojave Desert.

On a visit home, she found the inspiration she needed for her research from a familiar source. Harrower’s mentor from her youth, esteemed botanist Robin Koblay, tipped Harrower off to a new botanical discovery: underground networks of mushrooms that trees can use to communicate with one another. These mycorrhizal fungi networks grow on and within tree root systems and fan out into the soil, picking up extra water and nutrients in exchange for sugars from their host plant. Curious to see whether Joshua trees could be tapping into these fungal networks too, Harrower returned to her childhood home and dug up the roots of the one lonely Joshua tree in her yard for a closer look.

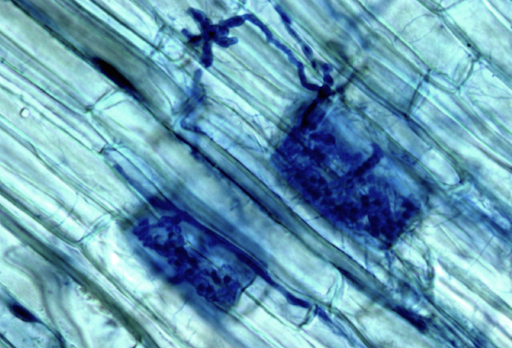

Blue-stained fungal structures branching into and filling Joshua tree root cells. Photo by Juniper Harrower.

She brought the roots back to her lab and got to work parsing apart the fine fibers. She boiled and dyed the roots before taking cross sections, as if she were slicing up a skinny carrot into thin circular coins. Under the microscope, she was able to clearly see the deeply stained branching networks of mycorrhizal fungi snaking through plant cell walls and branching out within cells like a microscopic tree. This was the first time any scientist had recorded the presence of mycorrhizal networks in Joshua trees.

Harrower was captivated by these interweaving fungi. She expanded her research across 11 different plots through increasing elevations of Joshua tree habitat in the national park. She wanted to know if the fungus’ relationship with the trees changed along with climate conditions along the elevation gradient. At each site, she took rigorous samples from Joshua tree roots and surrounding soil, collecting data on nutrients, temperature and other soil conditions. Samples of root systems and soil containing mycorrhizal fungi were transported back to her UC Santa Cruz lab on ice, along with the black bean-sized Joshua tree seeds.

Back at the lab and with the help of a soil analysis kit, Harrower was able to see that the populations of mycorrhizal fungi varied across each elevation, with a distinct mix of fungi with slightly different attributes at lower, middle, and upper elevation sites. Harrower painstakingly grew Joshua tree seedlings in a greenhouse to test how fungi from her different research sites impacted the growing plants. Each seedling was given one treatment, a dose of a mixture of soil and fungi from one of the 11 field research plots. After three, six or nine months she’d sacrifice her plants for science.

She found that fungi from different elevations had varying impacts on nutrient uptake and overall growth in seedlings. For example, fungi from the low hot elevations initially delayed the overall growth of seedlings as they borrowed carbon from the plants. At nine months, these plants experienced rapid growth as the networks started to pay off, pulling in more nutrients. Harrower was beginning to see a colorful world of underground interactions coming to life in her research.

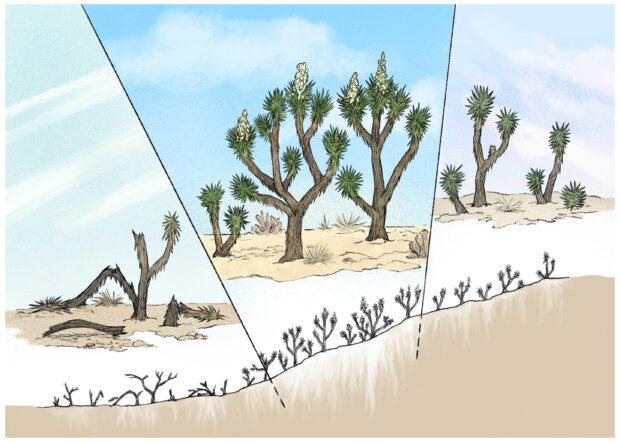

Joshua trees thrive at middle elevations, but wilt at lower elevations and fail to reproduce at higher ranges. Illustration: Emily Mitchell

“There’s so much happening underground that we take for granted… it’s almost more complicated” than life above ground, says Harrower.

Harrower reached for her paint palette to help visualize this subterranean scene. First, she attempted to paint what she was learning of these underground ecosystems – temperatures, nutrients, fungi and more – with acrylic paint, and then she started to experiment. She started dismantling Joshua trees, using elements from the plants in her paintings. She mixed Joshua tree seed oil and soap made from their roots into her paint to manipulate the textures on her canvas, creating a bubbling effect depicting the structure of the soil. She implanted fibers from Joshua tree leaves into burnt gaps in her canvas, visualizing root systems while incorporating the element of fire, a real threat in Joshua tree ecosystems.

Harrower’s paintings began to go beyond depicting still-life shots of the underground interactions of these trees. Harrower started to incorporate augmented reality to bring her paintings to life. When viewers lift their phones to these images, they see colorful depictions of Joshua trees shattering as new construction of homes and solar facilities take their place.

Harrower’s artwork had brought the perils of Joshua trees to the public’s eye. Soon, her research would inform people in another way, as her work was called on to support a movement to protect Joshua trees.

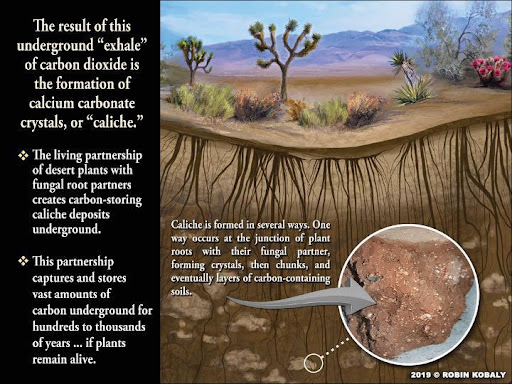

In 2019, Robin Koblay, Harrower’s early mentor, called on her scientist-artist protégée for help. The San Bernardino County Board of Supervisors, who make decisions for the largest county in the country containing the city of Joshua Tree, Joshua Tree National Park and a large portion of the species’ southern range, was about to vote on whether to ban large scale solar projects in the county’s unincorporated areas. Koblay wanted to communicate the ecological value of conserving desert habitat to the board, hoping to convince the supervisors to support the ban on development. Koblay knew that board members wouldn’t read a dry document. Instead, she proposed Harrower create illustrations of the dynamic subterranean desert ecosystem to accompany Koblay’s written word.

A page out of Kobaly and Harrower’s booklet, illustrating carbon storage in desert ecosystems. Illustration by Juniper Harrower, Graphic Design and text by Robin Kobaly.

Together, they crafted a booklet of illustrations of the fragile and important ecological interactions happening underground for each board member. The books arrived three days before the public comment meeting and were seen in the hands of the board members the day of. At the meeting, the board unanimously agreed to stop future solar developments without any deliberation behind closed doors. “They just listened and then they voted right then and there,” says Koblay. Koblay believes the booklets and their artistic display were central to the board’s decision.

Art Guides Science

Harrower’s art draws people into science and conservation, and sometimes guides her research itself.

One day during her mycorrhizal research, Harrower rested in the shade at one of her lowest and hottest collection sites in Joshua Tree National Park. As she rested, Harrower sketched a Joshua tree flower. Joshua trees bloom once a year (or every few years), all at the same time. But that day, she didn’t see a single guest in the flowers of the blooming trees that spread all around her.

Joshua trees are tightly tied into a relationship with their one and only pollinator: the tiny grey yucca moth. These moths are no larger than an apple seed and lay their eggs inside the plant’s yellow flowers. These unique pollinators don’t accidentally carry pollen from plant to plant, but actively collect pollen to pack down into the reproductive anatomy of another flower, raising the chances of successful pollination and fruit formation. Their babies will hatch and depend on this fruit, so the effort is worth its while.

Intrigued by the absence of moths at her hottest research site, Harrower started to examine the flowers at each of her research sites. Flowers at some sites had plenty of moths, while moths were completely absent from other sites. A year into her Ph.D., Harrower moved back home to expand her research, investigating this moth mystery across Joshua Tree National Park.

She designed a study to investigate where moths were and weren’t visiting Joshua trees, and what that meant for the future of these plants. With her infant son strapped to her back, Harrower spent over a year recording the numbers of moths, flowers, fertile seeds and signs of struggle in Joshua trees at all of her research sites.

Harrower found Joshua trees were in trouble at the lowest and highest elevations in their range. The yucca moths that pollinate the trees were scarce at the hot low elevation sites and completely absent at the cooler higher ones. Without moths, the trees can’t mix their genes, limiting the population’s future prospects. By identifying at what elevations moths were present, and how that correlated with the number of saplings and fertile seeds, Harrower’s research showed that moths and Joshua trees only thrive together at a narrow window, around 1200 to 1400 meters in elevation. This only represents a tiny fraction of their current range.

To Harrower, the implications of this research are clear: the precious healthy ranges of Joshua trees need serious protection now.

Policy

In 2019, the Center for Biological Diversity, a non-profit focused on protecting endangered species, petitioned the California Fish and Game Commission to protect western Joshua trees under the California Endangered Species Act. Their claim was based on the findings of Harrower’s research, along with others, showing the species could be gone from its namesake park by the end of the century.

In April of 2022, Harrower was shocked to see her research was used to make a case against enhanced protections. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife released a report ultimately recommending to not protect Joshua trees under the state’s Endangered Species Act. Despite Harrower’s and others’ research spelling the certain demise of Joshua trees without protection, the department concluded that because Joshua trees are currently bountiful – estimated to be somewhere between four and nine thousand across California – protection would be preemptive.

Harrower was dismayed. She spoke out at commission meetings and wrote letters addressing the misuse of her research. “The status review claimed a lack of demographic and climate data, however, they cited my peer-reviewed Joshua tree climate demography research over 20 times in the report. This is confusing as my work directly demonstrates these impacts,” says Harrower in a letter to the Fish and Game Commission. She claimed they ignored warnings of her and her colleague’s research in their final recommendation. “The general dismissal argument that Joshua trees are widespread and abundant and thus not warranting protection is a severe short sight by the department and a meaningless argument,” she adds in her letter.

On Feb. 8, the Fish and Wildlife Commission delayed its decision about future protections for Joshua trees for the fourth time. They said they are waiting to see if a new bill proposed by Govt. Gavin Newsom in the first week of February will be accepted in the CA legislature. The bill introduces The Western Joshua Tree Conservation Act, which would have similar protections as the ones offered to endangered species, but has more flexibility for continued development. If passed, the Department of Fish and Wildlife to have to prepare a range-wide conservation plan for the species by the end of 2024.

A Department of Fish and Wildlife fact sheet states “the permitting process for western Joshua tree is more complex than for any species currently listed under the California Endangered Species Act.”

Art Response

While the fate of Joshua trees and their legal protections are up in the air, artists are taking action.

On Feb. 10, Harrower and other Joshua tree-focused artists gathered at the Palm Spring Intersect Art and Design Fair. Harrower sat on a panel answering questions about the role of art and science in advocacy and showcased her ongoing project, “Hey J-Tree,” a dating app designed to help humans meet Joshua trees. Harrower estimates over 1000 people have participated. The project aims to bring joy into conservation: “You can swipe right on a Joshua tree,” she said as the crowd laughed. Harrower knows each tree featured on the website intimately, as they all came from her research sites across the national park, and encourages people to go find their tree in person. Harrower wants people to know that conservation isn’t all about doom and gloom–it can be fun too!

She hopes projects like this build intimacy between humans and trees, driving people to action. “When it comes down to it,” says Harrower. “We need to be building connections to places and to their incredible wonder if we want to keep them.”

© 2023 Roxanne Hoorn/ UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

Roxanne Hoorn

Author

B.S. (ecology and philosophy) Eckerd College

Internships: SeaGrant, Good Times, Mongabay

Years ago, you may have called me “Radioactive Roxy,” the host of your child’s science-themed birthday party.

I worked as a lab teaching assistant by day, but my partygoing side-gig got me out from behind the microscope. It showed me science in action as children gleefully put on bug-eye goggles to see like a bee.

Inspired, I left my lab coat behind to see where else science was hiding. I chased it as a guide in Southwestern deserts and Alaskan glaciers. I sniffed it out in community gardens while investigating the future of food systems.

Eventually, I started to see science through my own lens, including the one in my camera bag. Storytelling has become my way of exploring all the places science resides in our everyday lives. Plus, it gives me a new title: “Writer Roxy.”

Emily Mitchell

Illustrator

B.F.A (Studio Arts: Illustration, Ceramics Minor) Southern Utah University, Cedar City, UT

Internship: Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI)

My lifelong fascination with nature is what combines my love of science and art together. To accurately depict a bird, fossil, or natural phenomenon I am interested in, I turn to science. I find the research addicting! Every species I want to capture, be it common or rare, from the past or present, requires solving a mystery. Once my questions are answered, I’ve acquired new knowledge I get to carry with me. More importantly, I can share this experience with others. I studied illustration as an undergraduate and kept finding my way back to science. The continual process of discovering and learning about the natural world led me to pursue a career in science illustration.

Audrey Sauble

Illustrator

B.A. (English Literature and Creative Writing) Corban University, Salem OR

Internship: CSUMB Research Experiences for Undergraduates

As a kid, I was always interested in stories and in trying to write my own stories. Those attempts never went very far, though. Then, a few years ago, I started reading nonfiction picture books and informational picture books to my children. I hadn’t paid much attention to nature or science topics before that point. As we read more and more picture books, however, I discovered a passion for learning about the world. Eventually, my oldest and I had a conversation that turned into a picture book of its own. Ever since, I’ve been exploring different science questions through art and stories. When I discovered the Science Illustration program at California State University, Monterey Bay, it fit what I wanted to do, and I’m looking forward to learning how to use art to communicate science more clearly and more effectively.