Turning the tides for western pond turtles

Humans caused the decline of the western pond turtle, the West Coast’s only native freshwater turtle. Now, the San Francisco Zoo is raising hatchlings to reintroduce into the wild, McKenzie Prillaman reports. Illustrations by Cady DeLay and Anna Pedersen.

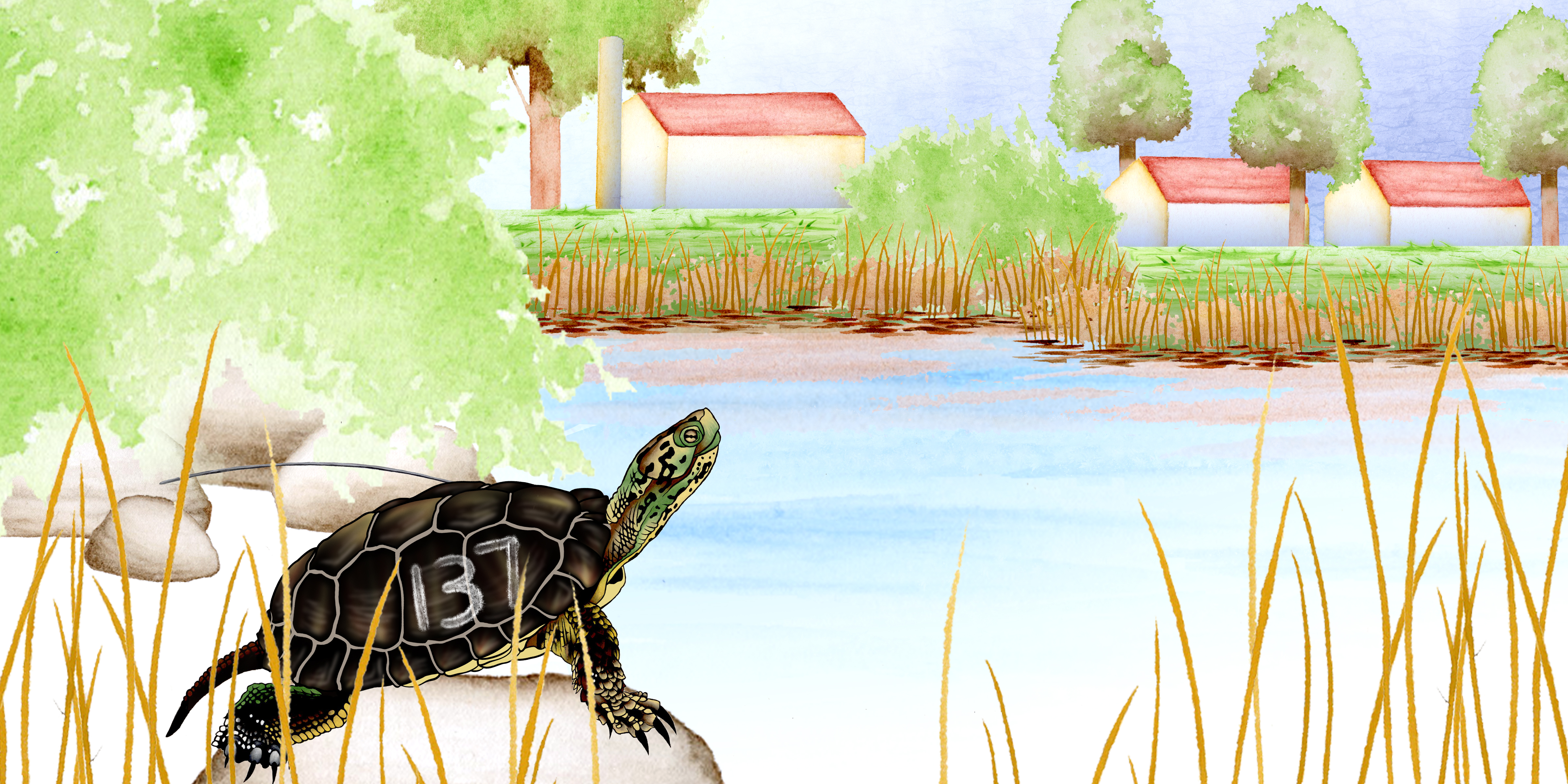

Illustration: Cady DeLay

A rowboat drifts atop a small, glassy lake encircled by a noisy highway, a bustling golf course and a lively playground. In this little aquatic refuge, two men row along to transport unusual cargo: young western pond turtles. The tiny, palm-sized creatures meander in clear plastic tubs resting in the boat’s hull as they await freedom in their new home.

The men stop rowing when they reach the lake’s western shore below Highway 1 and begin to place the animals one by one into the water. The turtles linger nearby. Some of the little ones climb onto neighboring logs while others bob in the surrounding calm waters. They patiently wait for the rest of their siblings to join them.

These turtles are among hundreds that have been released by scientists in a project aimed at reviving these animals—the West Coast’s only native freshwater turtle—after a devastating decline in number. On this September afternoon in 2015, Jonathan Young, a wildlife ecologist at the Presidio Trust, and Michael Boland, then the chief of park development and operations for the Presidio Trust, released dozens of western pond turtles into Mountain Lake in the Presidio of San Francisco.

Over the past 150 years, populations of western pond turtles—also known as Pacific pond turtles—have shrunk due to numerous threats, including habitat loss, predation, disease and exploitation by humans. Although millions of these creatures once flourished throughout the West Coast’s expansive wetlands, scientists have seen few at recently surveyed historical turtle sites. Researchers estimate anywhere between 10,000 and 1 million western pond turtles currently live in the wild.

“People think it’s just a turtle. But it’s not—it’s so much more than that. So many people are committed to this one species.”

Today, the San Francisco Zoo helps give these animals a fighting chance by raising hatchling western pond turtles during their most vulnerable period of life before releasing them into their natural habitat. After reintroducing nearly 400 juvenile turtles in central California over the past 15 years, this local conservation project aims to help recover a species that humans have driven to endangerment. The initiative is one of many stretching from Washington to Baja California working to bring western pond turtles back from the brink. An emerging shell fungus, however, threatens their efforts.

“People think it’s just a turtle,” said Jessie Bushell, the director of conservation at the San Francisco Zoo and leader of the institution’s turtle recovery effort. “But it’s not—it’s so much more than that. So many people are committed to this one species.”

An unusual phone call

One day in 2006, Bushell received a strange voicemail. At the time, she was an assistant curator at the San Francisco Zoo working with rescued and non-releasable animals, including western pond turtles, featured in live outreach and educational programs at schools and the zoo. Nick Geist, a professor at Sonoma State University who specializes in paleobiology, called to ask if the zoo—which lacked a conservation program at the time—could raise some baby western pond turtles. His new research project relied on the animal as a proxy to study dinosaurs.

“To be totally honest, I didn’t think it would go anywhere,” recalled Bushell, who now leads the zoo’s local conservation efforts. The message was vague, she said, but she felt compelled to return the call.

Geist wanted to study a biological factor that may have played a role in the demise of dinosaurs: temperature-dependent sex determination. In this phenomenon, an egg’s incubation temperature determines if the growing animal becomes a male or a female. Studies suggest that the dinosaurs’ egg temperature outcome was likely “cool boys, hot girls,” as Geist puts it, the same pattern observed in most modern-day turtles. Therefore, any dinosaurs that may have survived the asteroid crash 66 million years ago also had to endure the global cooling that followed—the space rock’s impact scattered dust and other chemicals that blocked out all sunlight. The new chilly climate would have caused all dinosaur eggs to develop into males. With only one sex, the dinosaurs couldn’t reproduce, causing their populations to dwindle to extinction.

To study this biological feature, Geist turned to the wild local turtle population—specifically, he wanted to study the development of their eggs. But one problem lingered: “I realized that I was going to have this side effect, this byproduct of the research,” Geist said. “If I did it, I was going to have a whole bunch of baby turtles.”

While talking on the phone with Bushell, Geist radiated his infectious excitement—Bushell compares him to the Energizer Bunny—and easily convinced her to help. Geist also enlisted the Oakland Zoo to join a new western pond turtle conservation project to help recover the species.

Turtle terrorizers

Western pond turtles once thrived in marshes, rivers, lakes and ponds along North America’s West Coast. Their densely populated historic range spanned from southern British Columbia, Canada, to Baja California, Mexico.

These hand-sized turtles are typically shades of dark brown and black with a pale yellow belly. Younger turtles sport intricate marbling on their shells and skin—the origin of their species name marmorata, Latin for “marbled”—but the pattern dulls with age.

In 1852, naturalists Spencer F. Baird and Charles F. Girard documented the first description of the western pond turtle. Prior to that record, the animal appears to have been a food source or ceremonial item for various Indigenous communities.

The mid-1800s Gold Rush, however, led to approximately 300,000 people moving to California. And they hungered for gold, fortune and turtles.

Around the turn of the 20th century, turtle soup—brimming with meat from multiple turtle species—was a popular meal in restaurants throughout California, especially in San Francisco. Matthew Bettelheim, a wildlife biologist, science writer and natural historian, says he uncovered more than 250,000 records of turtles to be eaten in the food market between 1863 and 1931. He estimates that an equal number went unreported.

Further, urbanization-driven habitat loss, degradation and fragmentation have drastically shrunk the wetlands that western pond turtles call home. Humans have transformed much of this natural environment into “useful” land for housing and farms, and roads also pose a significant threat.

An imbalance in turtle sex ratios disrupts populations as well. Since female turtles venture out of the water, sometimes more than 1,000 feet, into drier upland areas to nest, the slow-moving creatures are often struck by cars. As a result, western pond turtle males have increasingly outnumbered females since the early 1900s, and one study shows that the closer roads are to turtle populations, the more male-biased those groups tend to be. Climate change, however, threatens the opposite fate—since females are born at incubation temperatures above about 84 Fahrenheit, a warming climate may lead to an overabundance of girls. An unequal sex ratio leads to fewer eggs, contributing to the creatures’ decline.

“If you have a disturbance that knocks the numbers down, it really takes a long time to bring their numbers back up.”

Other animals also threaten western pond turtles. Largemouth bass and American bullfrogs—both invasive species—eat the tiny, soft-shelled hatchlings, and larger predators, such as coyotes, foxes and raccoons, feast on turtle eggs. Red-eared slider turtles, commonly released as unwanted pets and deemed one of the world’s most invasive species, outcompete western pond turtles for ecological resources, such as food and basking sites. Turtles need to bathe in sunlight to raise their body temperature; otherwise, they’re prone to infections and unable to digest food.

Although these turtles are robust animals that have been around for millions of years, they’re not prolific breeders. On average, females only lay seven eggs at a time, usually once per year.

“If you have a disturbance that knocks the numbers down, it really takes a long time to bring their numbers back up,” said Darren Fong, an aquatic ecologist of the National Park Service.

Gradually gaining protections

Today, western pond turtles have been completely extirpated from Canada, and the threat of extinction has been creeping southward. In Washington, the turtle’s population declined to an estimated 100 animals by the early 1990s, prompting the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife to list the species as endangered in 1993. Oregon considers the creature a sensitive species; researchers estimate the state’s population is declining in more than 80% of its range. In California, western pond turtles are a species of special concern, according to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, and recent drought years have been killing off southern populations.

Click on the data for more information. Population data from Nicholson et al. (2020). Range data from the U.S. Geological Survey and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Since the western pond turtle is the West’s only native freshwater turtle and a major predator in its habitat—consuming insects, tadpoles, fish—losing this animal could disrupt the ecosystem. The decline also concerns scientists because the resilient creature is a sentinel species that conveys the health of an ecosystem, much like the proverbial canary in a coal mine.

“When we start to lose native turtles, we have to start looking at our rivers and aquatic ecosystems,” said Jeff Miller, a senior conservation advocate of the Center for Biological Diversity. “[It means] our ecosystems are really out of balance and are not doing that well.”

The center first petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to list western pond turtles under the federal Endangered Species Act in 1992, but the request was denied. In 2012, the organization again advocated for the turtles to be added to the ESA.

A study published in 2014 aided the plea by using genetic data to reveal that western pond turtles actually encompass two distinct species. Northwestern pond turtles reside from Washington through the San Joaquin Valley, and southwestern pond turtles range from the central coast of California to Baja California, Mexico. Each species is more threatened than the formerly recognized solitary group.

In the year following this discovery, USFWS declared protection under the ESA may be warranted, and the final decision regarding each western pond turtle species is slated for 2023.

Waiting for turtles

In June 2007, Geist and his binocular-clad students each took several-hour-long shifts sitting more than 20 feet high among the trees of Boggs Lake Ecological Reserve in Lake County. They patiently waited for female western pond turtles to emerge from the lake in search of drier upland locations to lay their eggs.

Soon after a mother deposited her eggs and permanently left the nest—which Geist says is shaped like an upside-down lightbulb in the dirt—the scientists swooped in to gather the eggs. Without human intervention, the unhatched turtles made an easy meal for predators. (Mother turtles pee on the ground to soften the dirt before digging a nest, so predators can quickly sniff out the sites.) During the first field season, Geist recalled finding only two intact nests at the nesting site—hungry animals had plundered about 20 nests before the research team arrived. Pilfering predators, like skunks and raccoons, frequently wipe out the majority of freshwater turtle nests at these sites.

The scientists brought the fragile seeds of life back to the university and placed them in incubators. Letting the eggs develop in this controlled environment allowed Geist to determine the exact temperature that flips the switch between male and female.

But after realizing regulated temperatures didn’t mimic the naturally fluctuating environment, Geist and his team instead let the eggs develop on their own in the nests during subsequent years. They still descended on a nest soon after a mother laid her eggs, but now the researchers did so to insert a temperature sensor and cover the nest with wire mesh to protect the helpless eggs from predators.

Geist and his students returned in the fall to collect the eggs right before they hatched, along with the temperature sensors. Back at the lab, the researchers examined the nest temperature data and placed the eggs in incubators, waiting for the baby turtles to emerge. When the tiny creatures finally broke free of their shells, they were measured and weighed. The scientists then transported the little ones to the San Francisco and Oakland Zoos.

Giving them a head start

At the San Francisco Zoo, the conservation staff cares for western pond turtles of all ages and conditions—whether they have been hit by cars or are suffering from other ailments—as part of a local conservation effort, according to Bushell. During a tour of the zoo’s turtle rehabilitation facilities, she sported blue scrubs and sneakers, ready to spring into action whenever the animals needed her. The institution, at the time, was caring for 13 turtles from East Bay Regional Parks found on the brink of death during last year’s drought. The thriving but timid creatures hid under plastic logs floating in their kiddie-pool-sized tanks. Bushell and her team have since returned the turtles to their original pond.

The zoo is now deeply involved in western pond turtle conservation, but the project that started this entire effort was the “head start” program that began in partnership with Sonoma State University and the Oakland Zoo.

After receiving a turtle delivery from Geist, the hatchlings are placed in shallow water with a wet towel to acclimate to their new environment. “It’s a whole new world for these little guys,” Bushell said, warmth emanating from her voice.

For other head start projects, Bushell and her team take turtle eggs or hatchlings from the intended release site, or as close as they can get to it. Sometimes, they incubate the eggs at higher temperatures to ensure that females will be released to the site. The nests along central California’s chilly coast seem to be male-dominated, according to Bushell, so scientists want to make sure these populations can reproduce and sustain themselves.

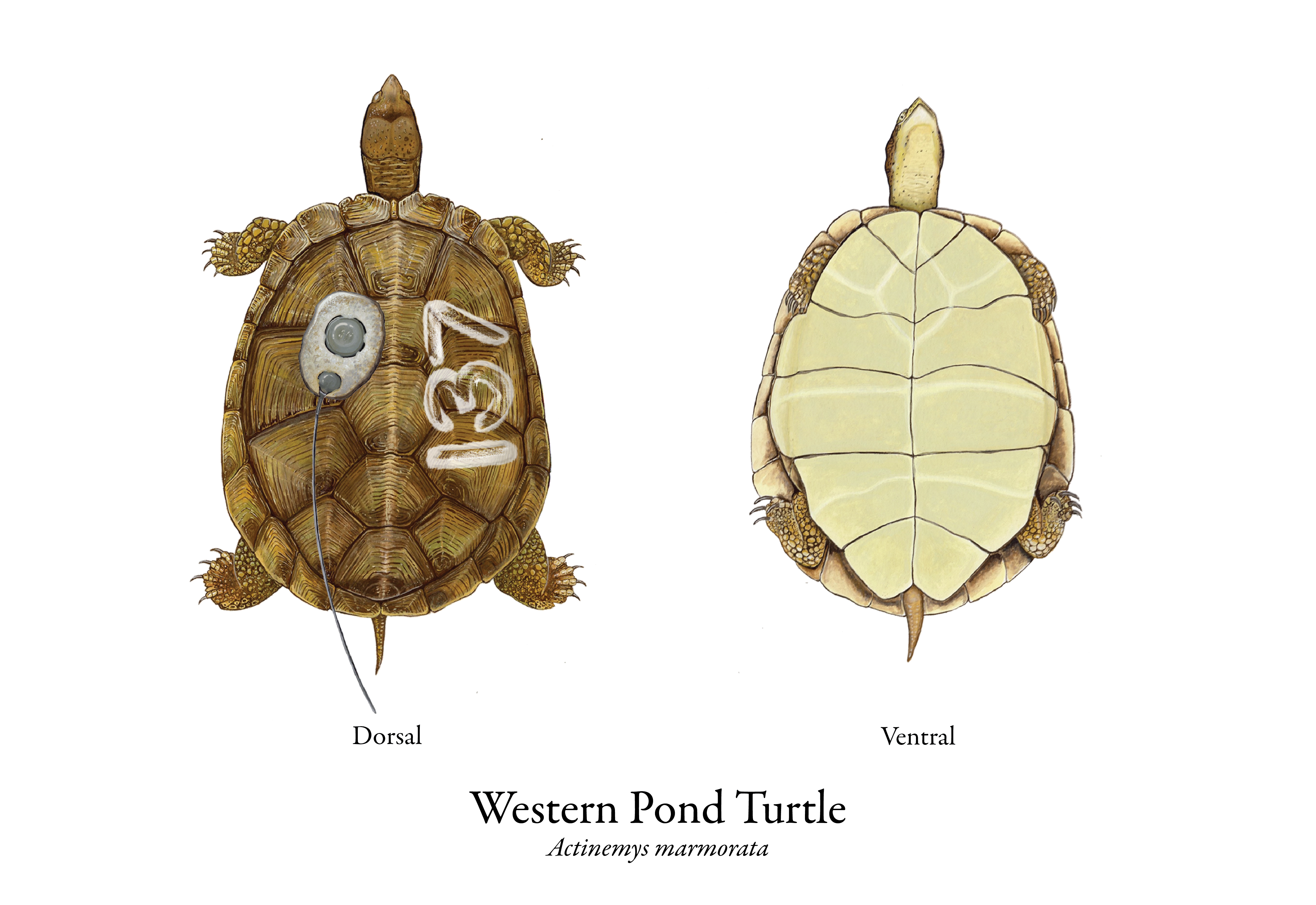

After a baby turtle’s yolk sac gets absorbed—which supplied nutrients for a few days after hatching—and the zoo staff ensures the young one can eat on its own and is gaining weight, it moves into an all-water tank. These 300-gallon vessels contain floating toys to hide under and bask on, plastic plants and UV heating lamps. A constant water current pushes around the turtles’ food, making the animals chase after their meals as they would in the wild. A few months before the turtles are released into the wild, the zoo staff surgically determines each turtle’s sex, implants a microchip—much like those used to identify lost pets—and notches the edges of their shells to help with identification in future years.

At two years of age, the turtles have grown enough to carry a radio transmitter device on their shells and evade predators. “We want them to be bigger than a bullfrog’s mouth,” Bushell explained.

A flurry of motion surrounds the young turtles on release day. Bushell and the other scientists take final measurements, make sure the turtles’ surgically-inserted microchips are functioning, paint identification numbers on the shells and attach battery-powered radio transmitters.

A head-started western pond turtle ready for release. Its shell contains notches, a painted identification number and a radio transmitter. Illustration by Anna Pedersen.

Typically, a crowd of curious-minded guests—biologists, educators, kids—gather at these events. Bushell and others involved in the project eagerly talk to them about the turtles and the conservation effort.

The day finally reaches its climax when the scientists send the turtles off into the wilderness.

“You put them in the water, and they pretty much disappear,” Bushell said. “They take off in the water—they go down, and they hide in the mud. Or they go over by the plants, and you’ll see their heads stick up.”

The San Francisco Zoo has released “head-started” turtles in five locations. Between 2008 and 2017, the zoo worked with Sonoma State University and the Oakland Zoo to release 210 turtles in Boggs Lake Ecological Reserve in Lake County. In 2015, Bushell’s team released 55 turtles in the Presidio of San Francisco, a former military post that is now a national park, in collaboration with the Presidio Trust and Sonoma State University. Between 2015 and 2017, they released 22 turtles in Yosemite National Park in partnership with the National Park Service. The zoo has continued working with the NPS to release turtles in the Marin Headlands just north of San Francisco—from 2017 to 2021, the institution released 42 turtles at Muir Beach, and between 2020 and 2021, they released 30 turtles in the Rodeo Lagoon. The zoo plans to release more turtles in Rodeo Lagoon in 2024.

Click on the data for more information. Data courtesy of Jessie Bushell/San Francisco Zoo.

A new threat emerges

Although so many people have worked tirelessly to recover western pond turtle populations, a new disease threatens their progress.

In the early 1990s, Washington almost lost all of its western pond turtles to an upper respiratory illness that ravaged populations across the state. Biologists responded to the epidemic by collecting all individuals left from the species (about 150 turtles), raising them in zoos then releasing them back into the wild, according to Max Lambert, an aquatic research section manager of the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

But scientists around the state soon noticed an issue.

“Just a handful of years later, they started recognizing that all the turtles that they were releasing that they had at the zoo had this pretty nasty shell disease,” Lambert said. “They basically have been managing it ever since.”

Pond turtle shell disease—named as such since it was first observed in western pond turtles in 2009—manifests grimly. The shell loses color and keratin in a process known as bleaching. The exterior forms pits, which Lambert likens to a fingernail rotting from the outside in. In extreme cases, the disease causes calcified bony growths from the shell to push down into the body, blocking movement through the animal’s intestines.

Now, the disease has spread to California. In 2020, Lambert, then a postdoctoral researcher at UC Berkeley, spotted a few red-eared slider turtles and western pond turtles in Santa Cruz sporting suspicious characteristics. But when tested, only the red-eared sliders came back positive for the fungus that causes the disease.

Although the western pond turtles were not carrying the fungus, Lambert still expresses concern. Red-eared sliders are “a vector for new diseases to native turtles not only in California but globally,” he said. These turtles have been released worldwide, which means they are likely spreading illnesses all over the map.

Since then, Bushell has been surveying Bay Area turtle sites to ensure the animals there are disease-free. Some scientists speculate that captive rearing played a part in the fungus’s spread since all of the western pond turtles in Washington were in a zoo at some point. So Bushell takes extra measures to keep her little ones isolated and avoid cross-contamination with other animals.

Promise and hope

Six years after Jonathan Young released western pond turtles in the Presidio’s Mountain Lake, he was trapping turtles at the site to sample them for pond turtle shell fungus. He stared out from his boat at a small patch of sandy beach and laid his eyes on a three-foot area of the lake’s shore free of tule grass and littered with alder tree leaves. As Young watched the water’s edge rise and fall on the shoreline, one leaf caught his eye. Then, it moved.

On that sunny April morning in 2021, Young spotted a baby western pond turtle, no bigger than a quarter, lifting its little head out of the shallow water.

Baby western pond turtle found at the Presidio of San Francisco. Courtesy of Jonathan Young/Presidio Trust.

Western pond turtles live long lives—about 50 years—and don’t reach sexual maturity until at least seven years of age. Young knew from the beginning of the reintroduction project that no one could claim a successful recovery for quite a while with this animal. A conservation effort “is not a success until you know that you have a new generation that is recruited,” according to him.

Although the initiative began as a way to study an ancient animal’s demise, it has turned into a critical piece of a network working to save two species from extinction.

“If you spot one baby turtle, chances are there’s more,” said Zip Lehnus, a community scientist. As a witness to the western pond turtle release at Mountain Lake back in 2015, he was awed when he saw the little turtle the day after it was found on the shore. Lehnus, moved by these creatures, now counts the turtles’ numbers from his window overlooking Mountain Lake and reports his findings to the Presidio Trust.

“It’s a baby,” Lehnus said, tearing up as he recalled the moment he laid eyes on the fragile, tiny turtle. “It represents promise and hope.”

© 2022 McKenzie Prillaman / UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

McKenzie Prillaman

Author

B.A. (neuroscience, minor in bioethics) University of Virginia

Internships: Stanford News Service, Monterey Herald, KSQD Radio, Nature

Does each person perceive sight, taste, and smell differently? How does a wild animal’s consciousness differ from ours?

As a child, these questions swirled in my head, enticing me to study the brain. When I discovered neuroscience—a field devoted to the mind’s biological underpinnings—I was hooked. For years, I tested animal behavior, sliced rat brains, imaged neurons, and analyzed data. I soon grasped, however, that meticulous research wouldn’t answer my expansive queries about humanity and the world.

Seeking to satiate my curiosity, I attended a talk by a scientist-turned-journalist. There, I realized that understanding the brain through research wasn’t my calling. I now understand people’s minds by climbing into their heads during interviews to craft enthralling stories about science. Through journalism, I can endlessly pursue questions and inspire wonder about us and our surroundings.

Cady DeLay

Illustrator

B.S. (marine science, minor in studio art) Stockton University

Internships: Mote, Monterey Peninsula Regional Park District

From a young age I wanted to study Marine Science and Art in college. And I ended up doing just that, graduating in 2019 with a B.S. in Marine Biology and minor in Art. Afterwards I struggled to find my next step, believing the only thing I could do was research. Then Covid hit, and any plans I had for the future went up in smoke. But, with that, I got time to think about what I wanted from my life. I realized my passion for art, education, and outreach were far greater than my “love” of research. Now, my future is much clearer because of this program. Being able to communicate information through art can be a challenge, but also fun and rewarding. This is what I’m meant to do, create art to educate and promote change.

Anna Pedersen

Illustrator

B.S. (conservation and resource studies, minor in global poverty and practice) University of California, Berkeley

Internship: Tetiaroa Society

Anna is a science illustrator and marine naturalist from the central coast of California. She received her B.S. from the University of California Berkeley in Conservation and Resource Studies with a minor in Global Poverty and Practice. She then went on to work for a number of different experiential education programs around the world before returning to school to receive her master’s certificate in Science Illustration from CSUMB. Anna is driven by her love for the ocean and loves to highlight the beauty that exists within it. She loves being in the field and using her experiences as inspiration for her art.

Fantastic story and incredible work!

Nice overview but some parts are not exact or off base. The species may have been introduced to extreme SW British Columbia. They now are extirpated. The shell disease is predominately in hed-started turtles in the Washington Stte program. Few elewhere have this problem, but recent surveys have no been published, yet. There are some large popultions remaining away from urban aeras. In one steram in northern California, I have caught, marked and released over 1,000 along a 3-mile stretch. That was over decades. A minimum of 500 mrked in one time period (3 yr). One waterway in San Joaquin Valley has 500 turltes. These large populations are scarce, but welack a solid survey of the species. They are stable or less theatened in northern Califonria and southern Oregon compared to souuthern California. It is under review possible listing at Federal level. Wait and see