Restoring Condors to Yurok Ancestral Lands

California condors nearly disappeared from the world by the 1980s, and haven’t graced the skies of the Pacific northwest in over a century. Now, Elyse DeFranco reports on the Yurok tribe’s journey to bring the birds home. Illustrated by Brittany Costanzo and Bridget Bailey.

Illustration: Brittany Costanzo

It’s a snowy spring morning in Redwood National Park, and Yurok tribal biologist Chris West is leading me into a dark room with a covered window at the far end. As he pauses at the entrance to remind me that we’re entering the “whisper zone,” I note the snowflakes melting into his handmade beanie, a carefully stitched vulture wrapping his head from temple to temple. I tiptoe over to the window as silently as possible, noting the binoculars and field notebook filled with notes about carcasses and feeding times. Slowly, I lift the blackout cloth and peer through the one-way glass. The birds we’re all here for are perched just feet away: the first California condors in the Pacific Northwest since 1892.

Brought to the edge of extinction primarily by lead poisoning from feeding on bullet-tainted carcasses, condors had nearly disappeared from the world by the 1980s, and have been slowly reintroduced to sites across the southwest for the last two decades. Now, the Yurok tribe has brought the birds home to their ancestral lands on the far northwestern edge of California.

Condors and their plight have played a key role in the American zeitgeist, on par with wild horses and bald eagles, as we projected our own meanings and symbolism onto the birds. Are they prehistoric creatures unsuited to survival in a human-dominated world, symbols for the perils of the loss of wilderness, or victims of the hubris of our gun-centered culture? As society grappled with these debates, the Yurok people – who have revered the bird for millennia – felt a spiritual hole in the world. For them, restoring condors has always been about far more than saving one endangered species – it’s also about healing.

“It’s really amazing to be the next big step for condors,” says Tiana Williams-Clausen, a member of the Yurok tribe and director of the tribal wildlife department. “To know that we’re restoring them to Yurok ancestral territory, and this is restoring an integral and indescribable part of our spiritual and ecological community – It’s a really big deal.”

Bringing Condors Home

The condor’s journey home to this far northern reach of the California coast began in 2003, when a group of Yurok elders gathered to assess how best to restore their ancestral territory. “For the Yurok tribal people, our foundational reason for being here is to be, as we say, ‘fix the earth’ people – we consider it our duty to keep the world in balance,” says Williams-Clausen. “The elders decided both for cultural and ecological reasons that prey-gon-eesh, the California condor, was the most important land-based species to bring back.”

The tallest trees in the world blanket the region of Yurok ancestral lands, where Redwood trees reach heights of over 350 feet. Photo by Elyse DeFranco

In Yurok tradition, their relationship with condors stretches back to the beginning of time. Condor feathers adorn regalia worn for world renewal ceremonies, which also center the song of the condor – chosen by the Creator as the “most beautiful, the most powerful” song of all the animals. As the highest flying bird in this part of the world, “We also believe that he helps carry the energy, or the prayers, of our dances out over the world, to help bring the world into balance,” Williams-Clausen says. “Not having Condor here to help bridge the gap between the spirit and the physical world to help make that balance a reality is very harmful to us as tribal people, because our entire reason for being is to make that balance happen.”

Bringing condors home is just one part of that balance, says Frankie Myers, Vice Chair of the Yurok Tribe. “It’s another step in moving towards restoring who we are as a people, who we once were, and building towards the future. We’ve worked hard over the last few decades, bringing our language back, bringing our dances back, healing our land and healing our people.”

Williams-Clausen was brought on to lead the condor recovery effort in 2008, fresh out of Harvard with a degree in biochemistry and the realization that her future didn’t, in fact, lie in medicine. Leading the budding condor reintroduction program gave her another way to serve her community.

For the next 14 years she worked through the process with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to get approval for the condor release. There were feasibility studies to conduct, and community outreach meetings to hold, and each time someone new stepped into the White House, the new government officials wanted to rewind the process. “It still feels a little bit unreal, because it seems at every turn, we’re finding some new problem that we have to circumvent,” she told me during the frantic last days of preparation before the birds arrived on site.

“She’s going to be the first generation of Yurok children to grow up with condors in over a century now. And that’s incredible to me.”

In March 2021, approval was finally granted. “I just had to sit down and cry a little bit, because it’s literally been my entire life’s work to make this happen…It’s been a hard 14 years.” As time dragged on, the original panel of tribal elders lost about half of its members, and Williams-Clausen says she felt a pang of guilt and failure with each passing. But her toddler daughter, Morgan, sits on her lap as she says this, and she turns to her. “She’s going to be the first generation of Yurok children to grow up with condors in over a century now. And that’s incredible to me.”

Jurassic Park

On a crisp January morning, West looks out over a sweeping vista of Redwood National Park, with layers of forest peeking through the creeping fog. The thick, dewey air feeds this part of the world, streaming in from the sea in the evenings and retreating in the mornings like a tide. The tallest trees in the world lie before us, thriving off the moisture that curls around them like smoke.

The stunning scenery doesn’t escape West, even though it’s the backdrop to his daily routine: hectic preparations for the condors, which are due on site in mere weeks. The Yurok team has partnered with the park to build their base here, an enormous enclosure which will house the birds while they adjust to their new surroundings.

It’s no small feat to prepare for the celebrity birds. The entire site – about the size of a football field – needs to be ringed with a 15-foot tall electrified fence. Even though it’s still in progress, the height is so imposing that it brings to mind Jurassic Park. West points out that, actually, dinosaurs never really went extinct – ok maybe the sauropods did, but the theropods (a group that included velociraptors and T. Rex) simply evolved into birds. (My mind wanders here to the recent news that, like their cinematic T.Rex brethren, condors are occasionally reproducing via parthenogenesis – virgin births.)

Careful genetic testing of California condors has revealed that the birds occasionally reproduce via parthenogenesis, or asexually. This photo shows an assisted hatch of a California condor at the Jonsson Center for Wildlife Conservation. © Oregon Zoo / photo by Kelli Walker.

The Jurassic Park site will not only serve to temporarily house the new arrivals, but will also be where the biologists leave carcasses for the birds once released, luring them back to the safety of the base with the irresistible scent of rotting flesh. The region is home to so many black bears that without the fence, bears would simply abscond with the meat.

Keeping the birds in the area has several benefits. As the condors gather around a dead cow, biologists will note who feeds first, in a quest to interpret their evolving social hierarchy. They’ll scan their bodies and behaviors for any signs of distress, which could signal that they’ve consumed fragments of lead bullets – the biggest threat to their survival – when they strayed away from their safe haven. At least once each year, they’ll trap the birds in order to test their blood lead levels and replace the batteries on the GPS tags attached to their wings. In fact, several people will be devoted to the birds full-time, tracking their every move, hauling carcasses on their backs, and displaying the focus and obsession characteristic of field biologists. West himself has been studying condors since 1999, and still lights up when he talks about their behavior. “That’s still where my heart lies,” he says. “I could sit and watch them interact socially all day long.”

A backhoe trundles over, and West waves the operator out. His name is Brandon Winkelman, and he’s being recruited to help build a special perch for the birds. West kneels in the dirt, sketching through mud and pine needles with his finger as he shares his vision. It’s important to have perches at different heights, he explains, because of their social hierarchy. Winkelman nods knowingly. “Just like a chicken,” he says. “I have chickens, I know how it works. There’s a pecking order.”

The men turn their attention to the enormous shiny metal cage, climbing on top of it, measuring and eyeing and clearly stressed that it won’t be finished in time. Like field biologists everywhere, they’ve had to become masters at troubleshooting, at imagining things to life, making do with what they’ve got. “We dreamed this up,” West says over the sound of power tools, a proud grin on his face.

He’s referring to the structure, but he might as well be talking about the entire condor reintroduction program. And it’s true – by sheer force of love and willpower, biologists brought this bird back from the edge of extinction. But it hasn’t been simple, and the journey is far from over.

Birds of Unusual Size

The first four condors of the new Yurok flock were born in captive breeding programs and moved to a large outdoor enclosure in central California last year to await the final preparations on their new home. As they spread their wings and adjusted to the climate of the Pacific coast, they also watched and learned from the Big Sur condors that visited the site to feed on carcasses and socialize.

On a dreary January day, I watch as their antics are live-streamed via the condor webcam. The black-headed juveniles are perched inside the enclosure, while just outside, four free-flying condors keep them company. A half-eaten calf carcass is picked over, while one condor stretches a wing in the sun. All of the birds, both the captive young and the free, are within pecking distance of each other. These remarkably social birds were fittingly assigned the literary group name of a “party,” the origin of which is obvious to anyone who saw the viral photos of them trashing a woman’s deck in Tehachapi last summer. Overturned flower pots and shredded bits of a spa cover dotted the scene, while bored-looking condors froze under the camera’s gaze like teenagers caught with their parents’ liquor.

Condors may not be conventionally attractive birds, with beady red eyes and faces of sagging, bald skin. They don’t have the regal stature of Griffon vultures, with their down-lined heads and dappled wings. They lack the majestic white collar of their closest relatives, Andean condors – though one could argue that evolution spared them the fate of the fleshy face-wattle that is reminiscent of both a chicken and a dinosaur. But they have a swagger to them, a way of seemingly defying gravity, that leaves even the least bird-interested in awe. They are, without a doubt, Birds Of Unusual Size: weighing in at 20 pounds, with a nearly 10-foot wingspan that could obscure a small car. Condors simply have a presence that is impossible to ignore, one that seems to clash with the modern world around them. They can be mistaken for an airplane when soaring overhead, and those who are lucky enough to get close to one in flight hear an audible “zing” of their hefty feathers. This has placed them squarely in the territory of Iconic Animal: Symbol of The West and The Wilderness.

And this status nearly led to their demise.

“Condors in zoos are like feathered pigs”

Condors roamed across the continent during the Pleistocene era, but by 1987, the world was left with just 27 birds. They’d been poisoned by ranchers, shot at by hunters, and even targeted for their feather quills, which were used by Gold Rush miners as vials for gold dust. And their biggest threat was only beginning to be understood: poisoning from carcasses contaminated by lead ammunition.

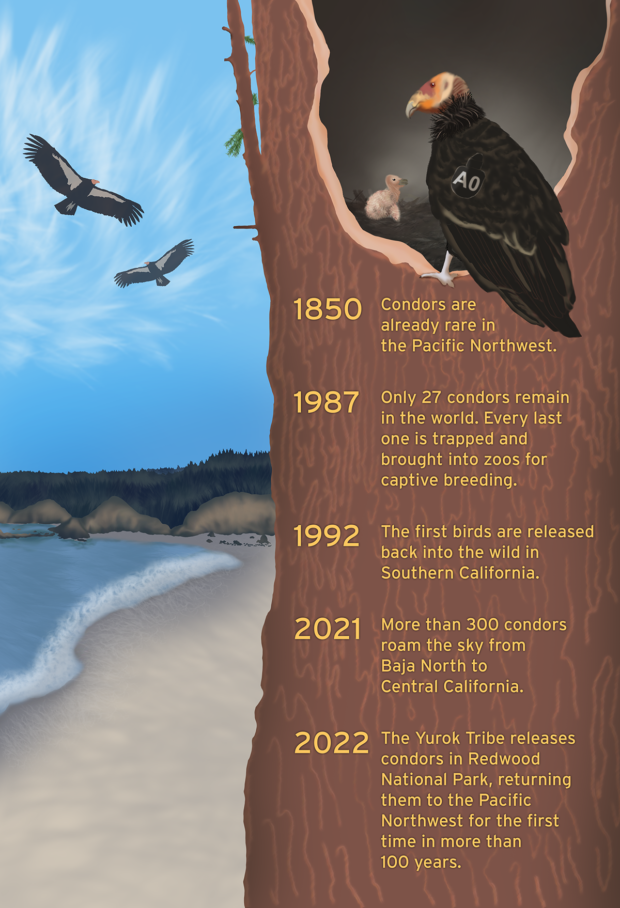

A timeline of the dwindling, and recovering, California condor population from 1850 to 2022. Art by Bridget Bailey

Biologists watched their decline with alarm. Jan Hamber, now the manager of the Condor Archive at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, first began tracking them in 1976. Often excluded from field studies by the small-minded men around her (“it’s been an interesting and torturous path,” she says), she jumped at the chance to spend days on end following the birds through the rugged and parched backcountry of Santa Barbara.

Now 92, Hamber recalls moments three decades in the past easily, recollecting the heated debate that grew around the birds’ plight. Unsure what was causing the last birds to perish, biologists couldn’t agree on how to save them.

“What you ended up with was two camps,” says Hamber.

One side saw their numbers drop perilously and insisted that captive breeding was the only solution. But many others saw this plan as short-sighted, believing that the birds needed more land protected from development. They feared removing condors from the landscape would mean losing what little wilderness remained in rapidly developing Southern California. And without vast landscapes to range over, their extinction would be assured. Some in this camp even advocated for “death with dignity” over captivity, with the prominent environmentalist David Brower going so far as to say that “condors in zoos are like feathered pigs.”

“It was hard for me to imagine the birds that I’ve watched that just lift themselves up on the uprising curve, and just soar so effortlessly above me … to think about them stuck in cages, I found very difficult.”

For Hamber, the debate was personal and heart-wrenching. “It was hard for me to imagine the birds that I’ve watched that just lift themselves up on the uprising curve, and just soar so effortlessly above me – circling without even flapping their wings – and then soar off as far as I could watch them… to think about them stuck in cages, I found very difficult.”

Hamber was eventually convinced drastic action was needed to save the birds when the female condor she had been tracking died a horrible death from lead poisoning. The winter of 1984-85 saw 6 condors meet the same fate. Less than 10 birds, and only one breeding pair, remained in the wild. As environmental historian Peter Alagona writes in Biography of a “Feathered Pig”: The California Condor Conservation Controversy, it was at this point that scientists came to realize that “if all condors, in all habitats, were now in danger of being poisoned to death, then no amount of wilderness could save them.”

Assurances that the birds would be held temporarily, with the goal of being released, helped sway Hamber. “And actually, I’m the person who called in the Trap Team on the very last bird, AC-9.” The pain in her voice is evident as she recalls the scene. “It was a very difficult time for everybody. You know, to switch from the excitement and the goal of protecting the land and protecting the species out in the wild, to taking every one of them into captivity was something that affected I think everybody on the program.”

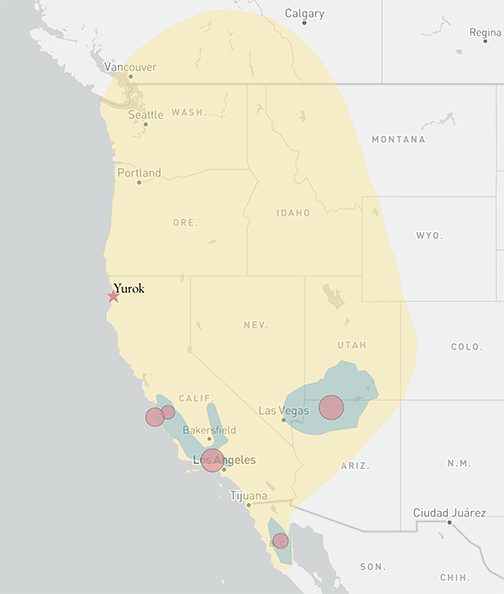

In 1992, five years after AC-9 was trapped, the first condors were released back to the wild. One of them was Xewe, the daughter of AC-9. Today, more than 300 condors roam the skies from Baja California to Big Sur, with the budding population at Redwood National Park greatly expanding their range northward. Another 200 condors are held in captive breeding programs. Even AC-9 returned to the wild 15 years after his capture. It’s an undeniable conservation success story, but the feathered pigs aren’t out of the woods yet.

A Labor of Love

As hundreds of dedicated biologists work tirelessly to increase the number of condors, the birds are released to a world where threats, nevertheless, remain. In some ways their recovery is easier than that of other endangered species, with condor habitat — vast, open spaces — still abundant in the West. But lead bullets are condor kryptonite, and human behavioral change is a slow and stubborn beast.

When a lead bullet pierces an animal, it explodes into thousands of tiny metal shards, transforming the carcass into a minefield for all scavengers: condors, eagles, ravens, coyotes – even humans. More than a dozen birds can gather at a single carcass, meaning one animal shot with lead ammunition can poison half a condor flock.

Although California banned the use of lead ammunition for hunting in 2019, the policy largely relies on cooperation by the hunting community. With many hunters balking at the restrictions, the threat of lead poisoning hovers over every carcass. Between 1992 and 2020, at least 107 condors succumbed to lead poisoning—as much as every other cause of death combined. But there is reason for hope. According to Dan Ryan, a National Park Service biologist who works to promote the transition away from lead ammunition, hunters are starting to see themselves as part of the solution. Rather than asking why they should make the switch, they’re starting to simply ask how. Falling prices on lead-free alternatives are also helping to ease resistance. “I think we’re getting there,” he says, “it’s just going to take some time.”

Map showing the range of California condors in the 1800s (yellow), their range in 2022 (blue), and the location and relative size of existing populations (pink). The Yurok Tribe’s flock greatly extends their current range northward, back to the Pacific Northwest. Data visualization by Elyse DeFranco

The remote coastal location of Yurok ancestral lands may offer the birds some refuge from lead-laden carcasses, and feeding on washed up marine mammals is safer for the birds. Unfortunately, there is a tradeoff, as even the sea can’t escape human contaminants. In southern and central California, residual DDT levels remain high in the tissues of marine life. This persistent chemical (which nearly wiped out bald eagles and peregrine falcons) thins eggshells, decreasing the likelihood that eggs will successfully hatch chicks. Somewhat promisingly, Yurok tribal biologists tested marine mammals in their region and found that DDT levels were seven times lower than they are in Big Sur.

Having condors successfully reproduce in the wild is key to their long term success, as most are still born in captive breeding programs in zoos and released. They nest in high tree cavities and rock ledges, and the sheer size of the remaining old-growth Redwood trees in this part of the world offer plentiful nesting habitat, with cavities large enough for a person to stand up and walk around in – perfect for the elephantine birds.

As if dealing with the persistent threats of lead and DDT poisoning wasn’t enough, condors are also killed by power lines. Occasionally, released birds will even have behavioral issues: without more adult condors in the wild to help them navigate the threats, they sometimes lack a fear of humans and will simply sit roadside, causing traffic jams as drivers gawk at the prehistoric animals. “The things you have to think about when you’re working with wildlife…” Williams-Clausen says. “There’s such a diversity of things I never thought I’d have to deal with.”

Like the biologists before her, Williams-Clausen will navigate the threats as they arise. Although the Yurok tribe is leading the effort, she emphasizes the ecosystem of support coming from the community, with “literally hundreds of groups and organizations” working to repopulate the skies.

The vast collective effort reflects the fact that condor recovery continues to symbolize more than just the survival of a single species: they’ve taken on the enormous weight of our hope for overcoming the sixth mass extinction – one driven not by a catastrophic asteroid impact, but by humanity. Watching as species drop from the planet with astounding speed, many have awakened to the idea that the animals around us take on cultural and emotional significance in our lives – and that losing them means losing pieces of ourselves.

The Yurok tribe’s relationship with condors celebrates them as symbols of renewal. It’s easy to understand why: rather than prey on the living, they feed only on the dead, and in so doing convert death and decay back into life. The herculean effort to bring condors back from the edge of extinction is only the most recent way that they’ve come to represent rebirth.

Condors A2 and A3 of the new Yurok flock shown inside their enclosure shortly before their release. Photo courtesy of Matt Mais and the Yurok Tribe.

“At last we fly!”

On the morning of May 3, I tune in from home for the Big Event: the day the first condors will be released from their enclosure, soaring free for the first time in their lives. Although closed to observers to ensure a peaceful transition for the birds, the live-streamed event draws hundreds of viewers from around the world – Spain, New Hampshire, Canada, Georgia – as people fill the chat with stories of their own condor encounters.

The birds are being gently offered their freedom, lured into the world with an open door and a fresh carcass.

Back in the whisper zone so as not to disturb the birds, Williams-Clausen narrates updates to the camera, the excitement visible in her eyes. People in the chat joke that the whispering makes the morning feel like “condor ASMR.” The four young birds seem relaxed, carefully preening feathers around the base of their wings, and a clear blue sky shines behind them. The nightly fog has already retreated.

Only two of the four birds will be released this time, with the next two released in the following weeks. This staggering will help draw the released birds back to the release site, where biologists will leave clean, lead-free carcasses for them to feed on. The team hopes to release 4-6 more birds each year for the next 20 years.

The whispers intensify as two young males, dubbed A2 and A3 for tracking purposes, approach the door. A3 is the first to enter the world, launching through the gate and immediately taking flight. A2 is only moments behind. Both birds soar off into the distance without any hesitation. The chat erupts with cheers and congratulations for the Yurok team. “I’m so deeply happy, so grateful for this day to finally come,” Williams-Clausen whispers into the microphone.

The pioneering birds are given Yurok nicknames: “Poy’-we-son” for A3, the first one to charge out of the door. “It means literally the one who goes out first, or ahead,” Williams-Clausen says, “and was traditionally the title of a headman, a well-respected leader in a village.” Condor A2 followed only seconds after, and is named “Nes-kwe-chokw.” It means, “He returns.”

Weeks later, A0, the first female of the budding flock, joins them. She is given the Yurok nickname “Ney-gem’ ‘Ne-chween-kah,” meaning “She carries our prayers.” When A1 – another young male and the final condor of the initial flock to fly free – is finally released in July, he is fittingly named “Hlow Hoo-let” for “At last we fly!”

© 2022 Elyse DeFranco/ UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

A version of this story was published on Audubon Magazine’s website in May 2022, and can be read here.

Elyse DeFranco

Author

B.S. (conservation and resource studies) University of California, Berkeley

M.S. (ecology and environmental sciences) University of Maine

Internships: California Sea Grant and KQED Deep Look

It’s easy to think of southern California as a crowded place filled with sprawling cities, and it’s true. And yet it’s also a place of rolling golden hills where a kid can catch frogs in the local creek and wonder at the curious bobcat playfully following her down the trail.

I kept at it through college and beyond, following my love for wildlife to remote research centers around the world. I jumped at every opportunity to learn about new research, from tracking hippos on a moonlit night to testing the geo-locating precision of satellite collars for baboons on my own neck. It didn’t take long to know that this state of learning and exploration sparked something in me that writing manuscripts and designing experiments didn’t.

I want the rest of the world to know this beautiful side of science too, as a messy process with real people following their curiosity to somewhere new.

Brittany Costanzo

Illustrator

B.A. (The history of art and visual culture) University of California, Santa Cruz

Internship: Ink Dwell Studio (Berkeley, California)

Brittany is a science illustrator from Santa Cruz, California. She received her B.A. from the University of California, Santa Cruz, in the History of Art and Visual Culture. After graduation, she began teaching the fundamentals of art and design for Drawn2Art in Scotts Valley and Los Gatos. After witnessing the beneficial aspects for children, and experiencing the joy of art education, Brittany decided to return to school and pursue a master’s certificate in Science Illustration from CSUMB. Equipped with her new set of skills and deeper appreciation for art and nature, Brittany hopes to teach and inspire others.

Follow Brittany on Instagram at @Costanzo_Creative

Bridget Bailey

Illustrator

B.F.A (pictorial arts) San Jose State University

Internship: Children’s Natural History Museum (Fremont, California)

Growing up in a family of artists in a small town in Northern California, my inspiration came from what was around me. I was lucky enough to have lived by a lake in the foothills of the Cascades, and spent most of my summer days outside swimming, making paintings, or doing photography. In high school, a friend convinced me to purchase a waterproof digital camera so we could take pictures in the lake, and that fateful decision marked the starting point of my career making art about the natural world. We were amazed by how much beauty could be captured underwater and I decided to pursue art and photography in college. During this time, I started working summers in Yosemite National Park. Influenced by the illustrations in my field guides, I began making my own field sketches. I realized my sketches were able to capture my time in Yosemite one step deeper than my photography was able to and I shifted course. Still inspired by the mountains, coast, and cities of California, I hope to educate and engage viewers in science through my paintings and illustrations.