A revered raptor’s return

By Jennifer Leman

Illustration: Charlotte Ricker

For decades, researchers have worked to bring bald eagles back from the brink of extinction. Jennifer Leman tracks their progress. Illustrated by Charlotte Ricker and Jessica French.

Glenn Stewart hovered in a helicopter high above a British Columbian rainforest. He scanned the canopy below through a pair of binoculars, looking for telltale clumps of dead branches. He’d traveled nearly 1,500 miles to get here in search of baby eagles – a desperate attempt to help save the species from extinction.

Suddenly, Stewart spotted a nest; he signaled the helicopter pilot to land nearby. But just then, an eagle swooped toward the craft. The pilot jerked down on the controls and veered the chopper away from the bird, narrowly avoiding a collision. Stewart was rattled, and asked the pilot to land the chopper for a moment. “I ran over and hung on a tree for a few minutes,” Stewart now recalls; unlike the eagles, he doesn’t like to fly.

Earlier that week in the spring of 1987, Stewart and a team of biologists from across the US had flown to Canada, piled into a van, and drove up through Vancouver, British Columbia, to a small coastal hamlet called Port Hardy. Eagles were disappearing from central California, but here, in western Canada, they were thriving. So Stewart, the director of an environmental organization, had come to collect eagle chicks. He would take them back to California, in hopes that they would repopulate the state’s dwindling eagle population.

Undeterred by their mid-air near miss, Stewart and his team boarded the helicopter and climbed aloft once again. They spotted another nest, and descended to the forest floor – this time, without incident. Wildlife scientist and tree climber Teryl Grubb exited the craft and shimmied up to the top of a redwood tree. On this trip, a crew from CBS Evening News had outfitted his helmet with a video camera. Stewart watched on a monitor below as Grubb recorded the scene. Suddenly, Stewart saw two wispy heads, two formidable beaks and two pairs of eyes peering into the camera lens.

“OK, who wants to go to California?’” Grubb murmured.

The Scourge of DDT

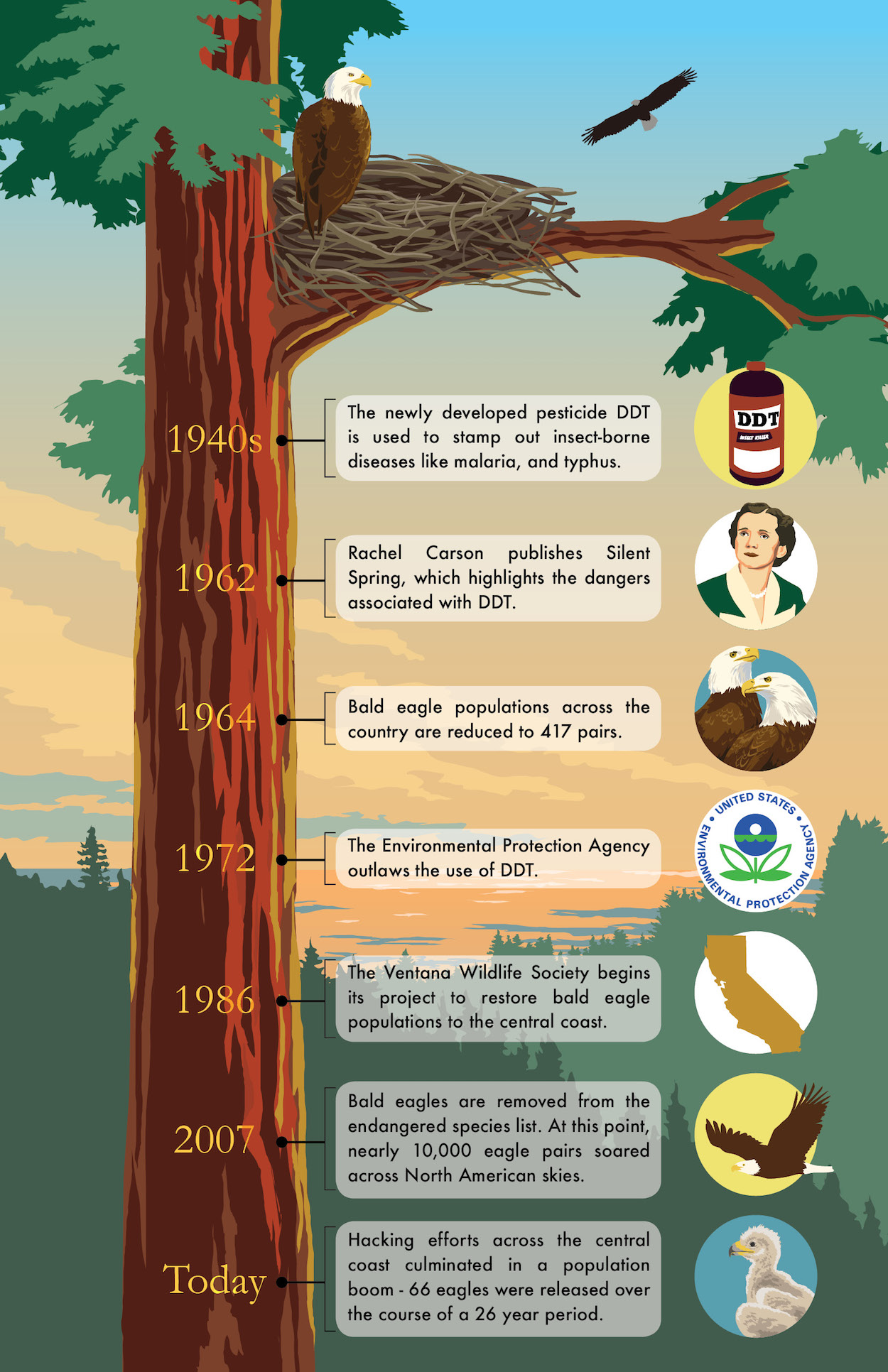

Stewart’s efforts were a last-ditch attempt to rekindle Bay Area bald eagle populations, which were decimated by the pesticide DDT throughout the 1940s, 50s, and 60s. DDT, short for dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane, weakened raptor eggs, killing baby birds before they could even hatch. The chemical ravaged eagle populations: by 1963, there were only 417 breeding pairs of eagles in the lower 48 states.

Stewart and other biologists worked tirelessly for decades to bring raptors back to the Bay Area. Now, more and more eagles swoop and dive for prey in central coast lakes and reservoirs – so many that the region is now trying to cope with the threat that hordes of curious onlookers pose to the eagles’ recovery.

“The bald eagle population is booming,” says Stewart, now the director of the UC Santa Cruz Predatory Bird Research Group.

Other conservationists credit Stewart’s work for the spectacular raptor recovery: “He’s really the raptor expert,” says Ralph Schardt, executive director of the Santa Clara Valley Audubon Society. Whenever community members have a question about the birds, “They call Glenn,” Schardt says.

Stewart, a passionate conservationist and advocate for falcons, eagles, and hawks, was inspired to study birds by Jean Craighead George’s book My Side of the Mountain, in which a twelve-year old boy lives in the forest with his falcon. As a high school student in California, he bought his own falcon and taught it to hunt. Stewart then attended college as an undergraduate at UC Santa Cruz, where he majored in political science. After learning about the school’s predatory bird research group, he returned to UCSC, and graduated with a second bachelor’s degree in environmental science. By then, he’d read Rachel Carson’s 1962 treatise Silent Spring.

This seminal book revealed the devastating effects of DDT, which had been sprayed on neighborhoods, farms and even people in the 1940s in an effort to kill the mosquitoes that spread malaria and typhus. The chemical flowed into streams and rivers, contaminating fish – the main prey of eagles and other raptors. DDT was lethal to raptor chicks. The chemical drastically lowered calcium levels in raptor eggs, weakening them so much that they cracked easily, killing the chicks inside.

Illustration by Jessica French

Stewart was alarmed by what he’d read. Though DDT was banned in 1972, its effects lingered all around him. Bay Area forests had been denuded; few raptor nests graced treetops and rocky outcrops. He decided to dedicate his life to bringing raptors back, and in 1986, became director of the Ventana Wildlife Society, which, since 1977, has worked to conserve native animals and their habitat throughout the central coast. Stewart was confident that central coast lakes and rivers were largely clear of DDT, and hospitable for bald eagles. Yet none could be found in the area.

So he hatched a plan to bring the birds back.Stewart would use a method called “hacking,” or importing baby eagle chicks from another place where they were thriving. If it worked, the baby eagles he brought to central California would breed and seed a new population of raptors. It had been tried with success in the Channel Islands in southern California and in New York state. So in 1986, Stewart got permission from Canadian and U.S. wildlife officials to capture baby eagle chicks from Port Hardy and relocate them to the Central Coast.

It was just a year later that Stewart and Grubb found themselves peering into the eyes of two baby eagle chicks in the British Columbian rainforest. Phase 1 of their plan had worked, but the project still faced challenges.

Stewart knew the plan was risky: “You’re taking that baby away from its parents, and you’re taking it to California,” he says. “You hope to God everything goes right.”

Grubb and Stewart retrieved the two eagle chicks, along with ten others they found in the British Columbian forest over the next week. They covered the eagles’ heads with a hood to keep them calm, then packed them into plastic crates and boarded them onto a jet at the Vancouver airport. Stewart knew the plan was risky: “You’re taking that baby away from its parents, and you’re taking it to California,” he says. “You hope to God everything goes right.”

When Stewart and his eagles landed in San Francisco, he drove them to a sprawling plot of land in Big Sur. There, he and his team had built a large wooden platform the eagles could call home. Stewart became their surrogate parent, feeding them ducks, geese and Muscovy that he caught in a nearby lake. A fisherman who needed to fulfill a community service requirement provided free fish for the birds.

For most of that spring, Stewart slept at a campsite near the platform so he could be close to the birds. He began spending nearly all of his time out there; on the weekends, his wife and children would join him at the camp.

Three months later, his team’s hard work began to pay off. One by one, the chicks fledged, diving off the platform to take their first solo flights. They began to leave the area in search of their own home territories. Stewart had fixed radio tagged harnesses to their backs, so his team was able to track most of their wanderings.

But many flew past the monitors’ range; juvenile bald eagles can soar up to 300 miles in a day. Some of the young fledglings made their way up to Canada and Alaska, thriving near salmon-filled rivers. But others stayed closer to home and built nests throughout the Bay Area. The eagles’ comeback was underway.

The Eagles Return

The Ventana Wildlife Society has released a total of 66 eagles into California skies. Many of those eagles have paired up and successfully reared chicks of their own.

Biologists in other regions have employed similar tactics to replenish populations throughout the United States. These efforts have been so successful that in 2007, bald eagles were removed from the nation’s endangered species list. There are now an estimated 5,000 breeding pairs of bald eagles in the Lower 48 states, and bald eagles populate skies up and down the Pacific Coast.

The eagles’ return has been a boon for local ecosystems because bald eagles prey on sick and injured birds, controlling the populations of the animals they hunt. Wildlife biologists also say that eagle populations help them track environmental threats. When raptors are suffering, it’s often an early warning sign that environmental hazards might harm other species as well, as happened with DDT.

“They communicate to us the health of our environment,” says Doug Bell, a wildlife biologist with East Bay Regional Parks, which stretches across Alameda and Contra Costa counties. The revival of bald eagles also promises future generations the opportunity to coexist with the national bird — an opportunity that once seemed like a distant dream. But our love for this iconic bird also poses threats to its continued survival.

In this podcast, Jennifer Leman reports on a pair of bald eagles nesting high above a Milpitas elementary school. Illustration by Charlotte Ricker.

At an elementary school in Milpitas, hand-scribbled pictures of bald eagles line the walls of classrooms. In spring 2017, an eagle pair built a nest atop one of the school’s redwood trees. That May, one of the pair’s hatchling successfully fledged and left to find its own plot of sky. The eagles are back again this year, and Esther Martosoetjipto, a science teacher at the school, is teaching her students lessons about the national birds’ food web. “We’re glad we could help the bald eagles feel at home in our own school,” Martosoetjipto says. But outside the gates of the school, camera lenses click and snap, aiming to catch the birds mid-flight. Raptor revelers flock to the school in droves.

Cindy Margulis, director of the Golden Gate Audubon Society, is concerned about the attention. “Now that we have them back, we have to learn how to live with them,” says Margulis. Amateur and professional photographers can unwittingly agitate bald eagles if they get too close. Margulis says that this can have devastating effects on a nesting pair of eagles: if crowded, they can become stressed, abandon their nest, and leave their chicks in the lurch. Clusters of photographers also call attention to the birds, and can signal to other animals that vulnerable chicks may be nearby. Crows and ravens are especially perceptive to these hints. “They clue in and they can come in and steal the eggs or the babies,” Margulis says.

To combat these issues, the Audubon Society recommends that photographers give birds a buffer, staying back far enough from the birds not to disturb them. The organization also only distributes ethically sourced images that don’t show visibly distressed birds; Margulis says that she can tell when a photo features a bird that has been harassed. Often, she says, they’re looking directly at the camera.

East Bay Regional Parks rangers have also worked to protect nesting eagles on their land. They’ve posted signs near eagle nests warning photographers to keep their distance, Bell says. Those who harass a bald or golden eagle can be fined up to $100,000 and jailed, but sometimes even these stiff consequences aren’t enough to dissuade the public from getting too close.

For these reasons, Margulis is reluctant to share the exact locations of nesting eagles when she discovers them. Once word gets out, it spreads like wildfire, thanks, in large part, to social media. Bird-watching apps provide a valuable link between enthusiasts and experts. But users are often encouraged to upload geotagged images of birds they see, and local online forums sputter to life at the first whisper of a rare species.

Looking Forward

Even those who aren’t avid birders relish sighting these raptors. On a recent January morning, Bay Area resident James Elliot was fishing at Quarry Lake in Fremont. As he fished, Elliott was surprised to see a young eagle dive into the lake hunting for prey. “It really put a thrill into our day of fishing,” Elliott says.

These days, Stewart spends less time climbing trees and collecting carcasses for ravenous chicks. Now, he satiates the hunger of a new flock: budding conservationists.

On a crisp Monday night in February, Stewart teaches an evening class about DDT at UC Santa Cruz’s Rachel Carson College – a fitting location for his lectures. Undergraduates file into the classroom, murmuring as they catch sight of a falcon perched on a post in the back of the room. Stewart tells the students not to give up in the face of bleak news about disappearing species. Like the condor, the puma, and the peregrine falcon, the bald eagle is a harbinger of hope. It’ll take a community, Stewart says, and “endless pressure, endlessly applied” to keep the bald eagle in the Bay Area.

He’s hopeful that this next generation will fight to keep the species safe.

© 2017 Jennifer Leman/ UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

Jennifer Leman

Author

B.A. (geosciences, museums concentration) Smith College

Internships: Science News (Washington, D.C.)

As a child, I was inspired by videos of volcanologists tiptoeing around rivers of lava. I created my own “heat-resistant” tin foil suit, ready to explore the hottest thing I could find—the oven in my family’s kitchen. Then, on a trip to Mount St. Helens, I learned that volcanic eruptions could be deadly. My fascination turned to fright.

Luckily, a college geology course drew my passion for science back to the surface. After graduating, I worked as an educator at a science museum and learned that I could relate anything from moon jellies to ostrich feathers to the ground beneath my feet.

In a tectonic shift, the volcanoes I once feared have become my greatest passion. Now I hope to use storytelling to illuminate both the wonders and hazards of this dynamic planet.

Jessica French

Illustrator

B.A. (Art and Design) University of Michigan

Internships: Ventana Wildlife Society (Salinas, California), Cornell Lab of Ornithology (Ithaca, New York)

As an artist, I love illustrating a variety of subjects, but since taking an ornithology class in college birds are particularly captivating. I hope to use my artwork to help people discover the variety and joyful nature of birds.

Charlotte Ricker

Illustrator

B.Arch (architecture) University of Tennessee, Knoxville

M.A (illustration) Syracuse University

M.F.A (illustration) University of Hartford

Certificate (natural science illustration) Denver Botanical Gardens School of Botanical Art and Illustration

Certificate (botanical illustration) University of Washington

Internships: Denver Botanical Gardens (Denver, Colorado), Filoli Gardens (Woodside, California)

As an avid outdoorswoman and world traveler, I have a deep love and appreciation for the wonders of nature, and enjoy narrating its miraculous stories through illustration and the written word. Many years as an Architect and planner allowed me the opportunity to design cities and buildings that celebrate both the mathematical order and beauty of nature. I now apply this methodical, analytical approach to my scientific illustrations. I am especially interested in studying the interconnectedness of all living things, observing the relationships between plants, birds and mammals, and the essential roles that each serves in their ecosystem. I strive to document my findings and observations in an artistic, informative and unexpected manner. When I am not in my studio, I can often be found exploring nature, conducting research for my art.