Cracking the case with pet DNA

The first accredited domesticated animal DNA forensic analysis lab is a vital tool for certain criminal investigations, Carolina Cuellar reports. Illustration by Keely Davies

Illustrations: Keely Davies and Michelle Buziak

The remains of Brent Justice’s victims lay scattered all over Houston. Their haphazard burials are evidence of Justice’s inconceivable cruelty. In the early 2000s, Justice and Ashley Richards, the woman in the Animal Crush videos, tormented small animals–usually puppies–on video for their clients’ sexual gratification. When the Houston police department received a tip about Justice’s occupation, they discovered that he was the man who spoke behind the camera in these videos and handed Richards the knife that she used to carry out her clients’ requests.

Justice chose denial as his first recourse upon arrest. Deny he was the cameraman. Deny his role as the merchant, producer and distributor of the videos. And deny that a blood spatter that detectives found on the wall of his home had anything to do with the animals’ death.

Initially, Justice claimed the blood on the wall belonged to his housemate.

Investigators suspected he was lying, but weren’t sure how to prove it. A forensic lab could show that the blood wasn’t from a human, but that might not convince a jury that Justice and Richards had killed the actual animals depicted in their videos. Investigators needed to trace the blood’s origins to an actual victim – ideally, the puppy who’d been tortured in the video they planned to show in court as evidence of Justice and Richard’s crimes.

There was only one lab they could turn to: The Forensics section of the Veterinary Genetics Lab, or VGL-Forensics, at the University of California at Davis. It is the first and one of the only regulated DNA forensic labs that specialize in domesticated animals. The bloodstain stains on Justice’s wall were swabbed and sent to Davis, where the forensics team identified the blood as canine and feline, adding a critical piece of evidence to the case against Justice. The blood didn’t come from his housemate, it came from the animals in the videos.

DNA labs, like Davis, are advancing the field of criminal justice.

Labs with the ability to identify different species through DNA are rare, but in cases like Justice’s, they’re vital in forming a connection between animal victims and their perpetrators. Now, VGL-Forensics is performing complex domesticated animal DNA analysis to prosecute crimes when other evidence is not enough to link humans or animals to a crime. Just as DNA analysis can be used to distinguish between individual human suspects or victims, investigators use animal DNA to distinguish between different animals that may have been present at the scene of a crime. That genetic evidence can be an influential clue that leads to justice for animal and human victims in a variety of animal and human cases, such as animal abuse, domestic disputes and murders.

Finding Crucial Links

The lab was formed twenty-two years ago and first made its mark in investigations of illegal dogfighting rings. Dogfighting is a sport in which two dogs are trained to fight each other until they’re dead or immobilized from their injuries. It’s illegal federally and in all fifty states. Many dogs are related to one another because they’re bred from within a group of fighting dogs. Because of this, a good way to find the humans behind dogfighting rings is to test whether their dogs are genetically linked. The idea to create a database to find these linkages came in the wake of the largest dogfighting seizure in U.S. history, known as the “Missouri 500,” in 2009. After rescuing over four hundred dogs from 23 sites, supposedly all related to one organization. Melinda Merck, a then-member of the ASPCA, thought of using DNA from the seized dogs to prove that the owners from each site weren’t independent breeders and were all involved in a single dogfighting ring. Elizabeth Wictum, the then Director of the VGL-Forensics, agreed to process over two hundred samples to analyze whether all the dogs involved were related to each other. From this, the ASPCA realized the utility of a dogfighting DNA database for future criminal dogfighting investigations and it became an established resource for law enforcement at the VGL-Forensics. Today, for any dogfighting-related seizure, agencies can submit a buccal swab–a swab from the inside of a mouth–to contribute possible parental matches or find existing ones.

The investigation of animal crimes can also pin-point people who may commit violent human offenses. Although Merck works in the animal sector, she’s seen a change in attitudes towards animal abuse, particularly in relation to humans. “I think it’s been societal. We’ve started seeing more laws passed as the recognition of the link between animal cruelty and the perpetrators of animal cruelty with other crimes, particularly with domestic violence, family violence, child abuse,” she said. Like Jefferey Dahmer, many serial killers began by inflicting violence on animals. In 2002, psychiatrists found that prisoners with histories of animal cruelty were much more likely than prisoners without animal cruelty charges to have Antisocial Personality traits or the disorder–a mental disorder in which a person doesn’t care about others. A different 2020 study reported that “A large and growing body of scientific research demonstrates the correlation that can exist between animal abuse, child abuse, and family violence.” A 2007 study found that women in domestic violence shelters were eleven times more likely to report violence against pets in their homes than women outside the shelter who did not report any violence. Additionally, a portion of the women in the shelters said that violence and concern for their pets kept them from leaving an abusive partner sooner.

In 2007, for instance, teenage brothers Justin and Joshua Moulder abused a dog after vandalizing an apartment complex’s multipurpose room. Later they bragged about their actions to neighborhood children and threatened to kill them if they told anybody.

The Moulder brothers were charged with burglary, criminal damage to property, terroristic threats, cruelty to children and aggravated animal cruelty. Prosecutors used dog hair from one of the brother’s backpacks to connect the boys to the deceased puppy, strengthening their argument that the boys had killed the puppy after picking it up off the street. The disturbing testimony by the veterinarian on the scene, which described the puppy’s anguished struggle, compelled the judge to make an unusual request that he be allowed to examine their juvenile records.

The judge discovered that one brother had previously been accused of threatening to kill his foster mother. The other brother had a previous conviction of sexual battery of a three-year-old boy.

For both brothers, animal cruelty was part of a pattern of unhinged violent behavior. This relationship between animal and human crimes is so persistent that in 2008, veterinary, behavioral and academic authorities dubbed this relationship “the Link.” As data builds up about this connection, resources like animal DNA analysis may be even more important in connecting animals to human crimes.

Through Court Trials and Scientific Tribulations

The VGL-Forensics, founded in the 1950s, started out using early genetic technologies to study agricultural animals, including horses and cattle. In the 1990s, law enforcement began asking the lab to profile cats and dogs for criminal cases. One of these cases–in which pet DNA placed a perpetrator at the scene of an attempted sexual assault–demonstrated the need for a forensically-accredited DNA crime lab that could do this type of work. The lab had to modify many human DNA analysis tests to adjust for the differences in human DNA vs dog and cat. The VGL director at the time assigned Elizabeth Wictum, future director of the lab, to create the rigorous procedures needed to help solve criminal investigations. The accreditation process–which took about ten years–involved proving that the lab’s procedures resulted in accurate and reproducible data.

Her work paid off when, in 2010, they became the first dog DNA lab in the world to get forensically accredited. That meant that the evidence from the lab meets the standards at which other forensic labs, including human, operate to process and produce admissible evidence.

The VGL-Forensics, currently composed of four staff members, works about eighty cases a year. Out of these eighty cases, one or two usually make it to court. International investigators from South America, Japan, the United Kingdom, Canada, Bermuda, New Zealand and Australia have also called the lab requesting their technical support and expertise.

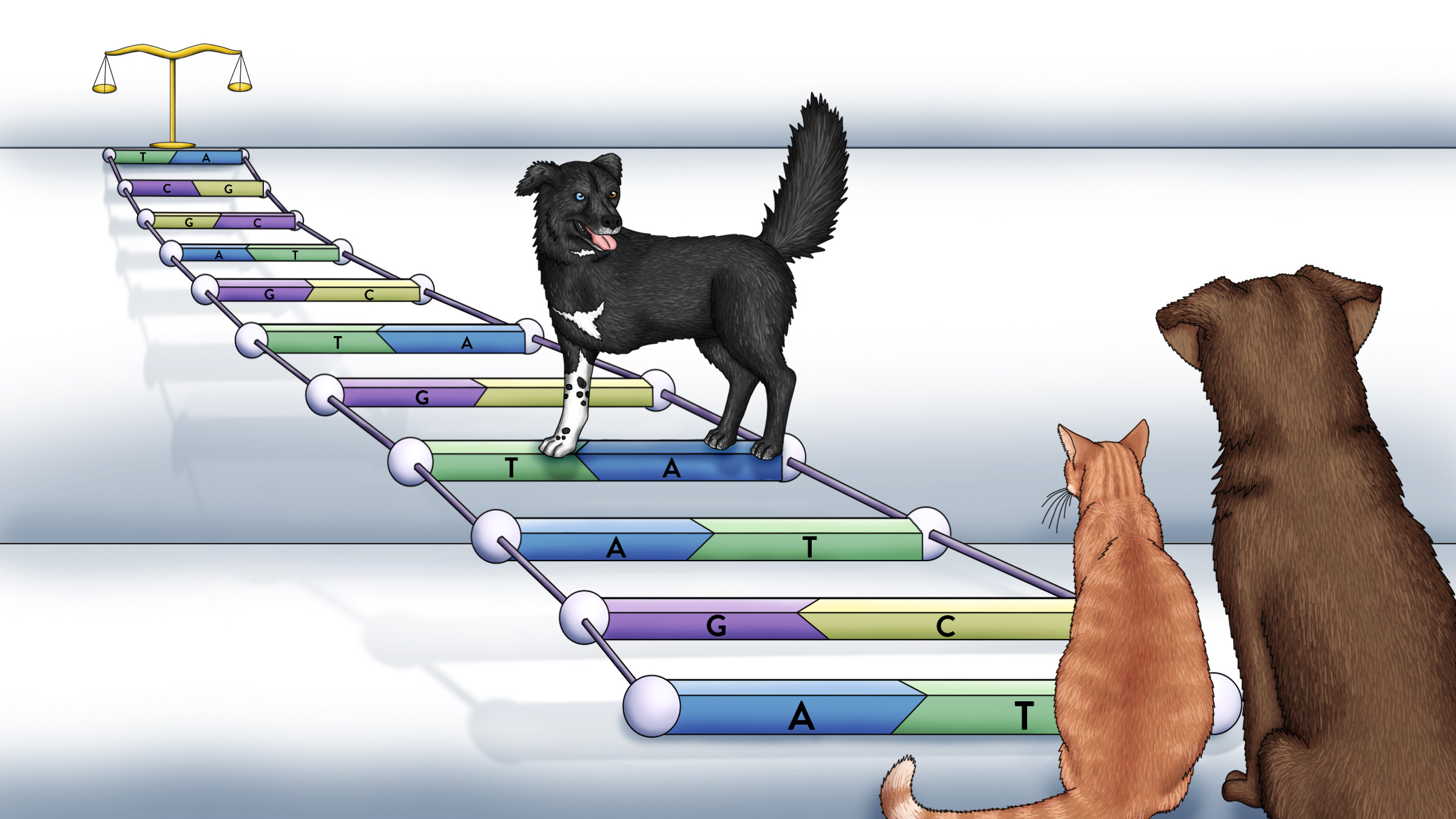

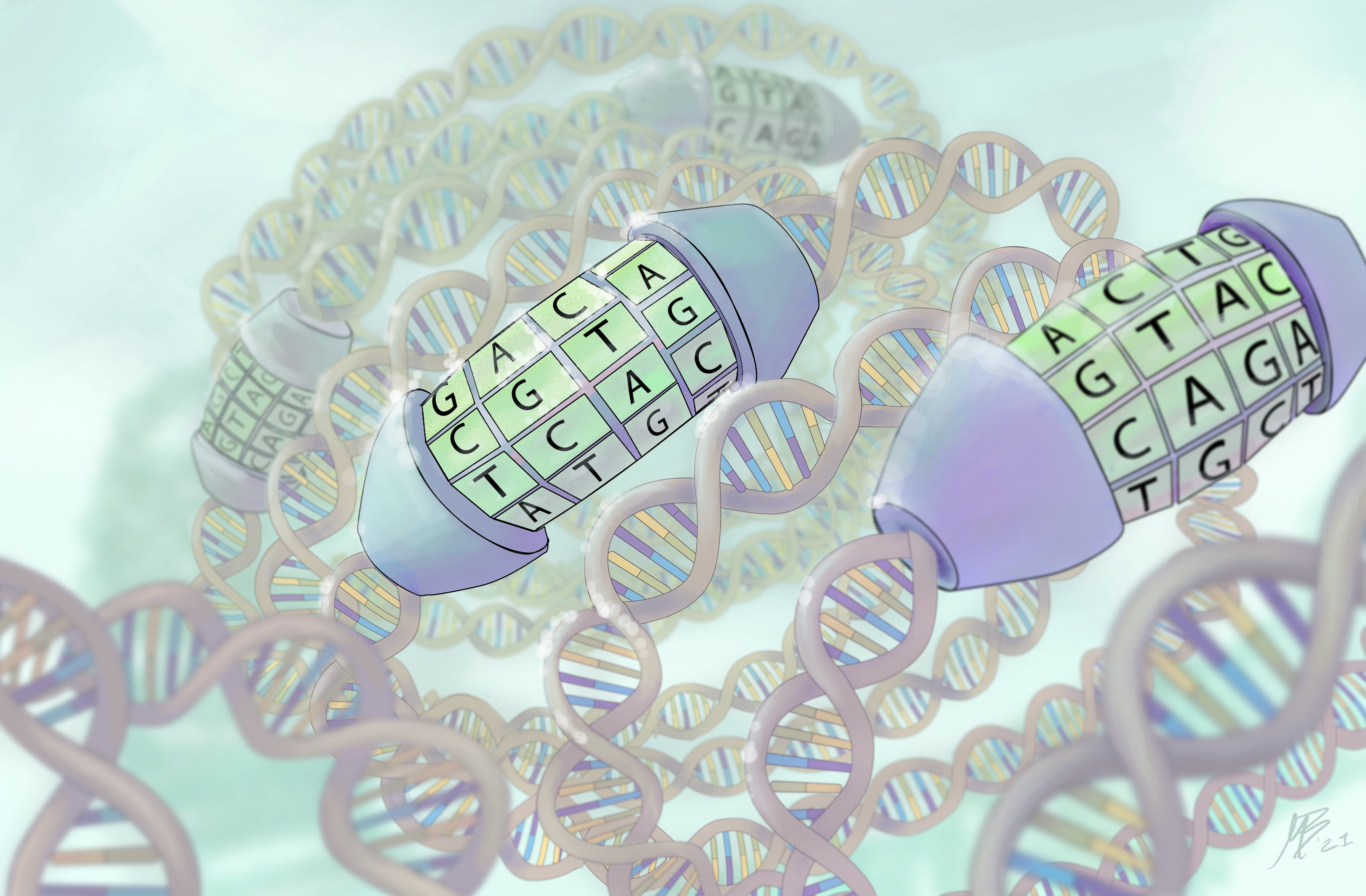

The lab uses similar procedures to those used by human forensic labs. To understand how DNA identification works, it helps to imagine a combination lock–like those found on high school lockers. The lock itself can be compared to a segment of DNA from a sample left at a crime scene. The unique pattern of genetic markers in each sample of DNA is like the unique series of digits that opens a combination lock. To identify the source of the sample DNA, criminalists examine the genetic markers within it, then compare them to a reference sample. If both segments have the same markers, the segments of DNA come from the same individual human or animal. In the lock analogy, it’s as if the criminalists found two locks with the same combination code.

Now imagine that a person has two locks, one from their father and one from their mother. By comparing the suspected parents’ locks to one of the subject’s locks, criminalists can determine if the alleged father and mother are indeed the parents.

The types of genetic markers that criminalists analyse are called Short Tandem Repeats, and they measure how many repeating DNA bases appear in certain segments of DNA. Scientists can use these short tandem repeats to construct detailed DNA profiles of suspects, including linking them to parents.

But this level of specificity isn’t always necessary for cases that involve animals. Sometimes just knowing the species present, or the brand of the lock, during a crime is sufficient. In these situations, criminalists can look at a single genetic marker that differs between species in an analysis called DNA barcoding. An added benefit of this analysis is that it requires a type of DNA that is in much higher abundance, making it easier to analyze.

Both DNA profiling and barcoding lend themselves to a breadth of criminal cases. The methods can be used to solve trivial problems, such as identifying the owner that doesn’t pick up after their dog. They can also be used to place a perpetrator and their dog at the scene of a crime. In animal cruelty cases, these analyses can identify fluids at a crime scene to prove that they belong to the abused animal or species. For these more serious cases, criminalists’ duties may include processing the sample and later testifying in court. However, the latter is rare because of the reliability of DNA evidence, said Christina Lindquist, the current Associate Director of the VGL-Forensics.

“We find that often, once the DNA from animals hits the court, the defendant just doesn’t want to try anymore,” she said. ”Our evidence is very persuasive in terms of soliciting plea agreements.”

Pet DNA also has its advantages. Often, It’s hard to obtain a good human DNA sample from a scene in high quantities. In hair, for example, the follicle has to be intact for DNA to be analyzed. Dog and cat fur is a different story. Because both species lick themselves, especially grooming cats, their hairs are commonly covered in DNA from saliva, increasing the chance of extracting DNA from it. Additionally, furry animals shed more than humans and don’t discriminate where they leave their genetic evidence.

However, there are significant limitations to the widespread use of animal DNA analysis. Depending on the case, the funding for acquiring evidence is limited to nonexistent. Many of the abused animals come to shelters where a single DNA analysis could cost as much as caring for 300 dogs. Organizations like the Animal Legal Defense Fund provide grants for this type of analysis, but the time from grant application to disbursement often outlasts the case’s lifetime. Oftentimes, animal abuse isn’t discovered until it reaches a veterinarian who either has no recourse, or means, to notify law enforcement in time to investigate and build a case.

To Help An Owner Through Their Pet

Funding to use animal DNA evidence to solve human-related crimes is more generous. But the field is so new and sparse that law enforcement agencies are often unaware that it’s even a possibility. Organizations like the International Veterinary Forensic Sciences Association are working to educate law enforcement agencies about the potential for this technology. They also emphasize the importance of shelters and veterinarians having easily accessible legal resources to make it easier to pursue legal action against perpetrators. Both for the sake of animal and potential human victims.

For example, Brent Justice, the Houston producer of the illegal puppy torture videos, had acted violently towards humans well before his “crush video” arrest. In 2000, Justice allegedly hit his then-wife in the head with a towel rack. In 2007, his then-eighteen-year-old daughter called the police and claimed he assaulted her; the officers called to the scene noticed visible scratches and bruises on her body. And just before his arrest for producing the crush videos, Justice had threatened to kill his brother’s ex-wife over the phone.

As the recognition of the relationship between animal cruelty and a perpetrator’s predisposition for violence grows, lawmakers have responded through legislation. The Pet and Women Safety (PAWS) Act was signed into federal law as part of the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018. The bill provides protection and resources to aid abuse victims who want to leave their abusers and take their animal companions with them. It aims to stop victims from staying with abusers who threaten to harm a pet if the victim leaves.

In 2016, the Federal Bureau of Investigation also started recording animal cruelty offenses to track national links between animal cruelty and other violent crimes. In addition to more research and preventative education, the National Link Coalition advocates for psychological intervention and changes in public policy to include higher penalties for and protections against animal cruelty or abuse as ways to address the Link.

Justice Through Hope

For now, however, animal DNA analysis is still seen as relatively niche and supplementary to a greater body of evidence.

“Most of the DNA cases, even the most serious ones, the animal DNA isn’t the smoking gun. It’s not the thing that solved the case. It’s a piece of a much larger puzzle that often includes human DNA. And sometimes it’s just the path to the way to get that human DNA,” said Lindquist.

Prosecutors like Jessica Milligan hope to change this. Milligan has seen the power of forensic animal DNA identification firsthand. In 2009, when Milligan was an Assistant District Attorney for Harris County, she decided to start working animal cruelty cases after adopting her dog, Hope.

Hope was a cute, three-legged furry black canine. But for Milligan, Hope’s defining features were her compassion, intuition and steadfast resilience as a survivor of animal cruelty. Perplexed at the unnecessary violence inflicted on Hope, Milligan made it her mission to protect and advocate for animals. That led her to develop expertise in animal cruelty cases — and, in 2012, to become the lead state prosecutor on Brent Justice’s animal cruelty case. Based on the evidence identified at the crime scene, including canine DNA, Milligan got Ashley Richards to plead guilty and agree to testify against Justice, who chose to represent himself at trial. Justice tried a litany of unsuccessful defense strategies, including dubiously claiming that the animals were sacrificed in the practice of his Jewish faith. Unluckily for Justice, however, federal lawmakers had just passed the Animal Crush Video Prohibition Act twenty-two months before his trial, and federal authorities also launched a case against him — the first animal crush case tried in federal court under this legislation. Justice was ultimately convicted of one state count and four federal counts, resulting in a twenty-one-year prison sentence.

For these types of crimes, sorrow is inextricable from justice. Milligan says that no one involved in Justice’s case was ever the same after watching his horrific video productions. Unfortunately, the types of cases that compel lawmakers to enact preventive or punitive policies are the most outrageously heinous–the blaring red sirens policymakers can’t ignore. Hope died in 2020, but her legacy still compels Milligan to work animal abuse and cruelty cases by using every available investigative resource.

“There aren’t many labs out there that do animal DNA,” said Milligan. “But it’s vital help for some cases and DNA labs, like Davis, are advancing the field of criminal justice.”

*an enhancement on his state charge, use of a deadly weapon, was voided. It dropped his state sentence from fifty to twenty years

© 2021 Carolina Cuellar / UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

Carolina Cuellar

Author

B.S. (Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology) University of California, Santa Cruz

Internships: Santa Cruz Sentinel, KQED, Inside Science

I report for Texas Public Radio through Report For America where I cover business and border issues.

A scientist-turned-journalist, I worked on the science desk at KQED, for various science news outlets, and have written about the largest fire in Santa Cruz County history, the CZU Lightning Complex wildfire that started in August 2020 and border policy under Biden. My work has appeared in NPR, NBC News, ABCNews, The Mercury News, and science sites such as Inside Science.

Michelle Buziak

Illustrator

Michelle Buziak is a science illustrator, focused on creating art that strengthens her local community’s connection to the natural world. From fluffy birds to fossilized fishes, she draws inspiration from the incredible evolutionary diversity of plant and animal life. She hopes to cultivate in others a sense of wonder and an urge to protect what surrounds us, with an emphasis on the plants and animals we are at most risk of losing. She also has great interest and takes great personal inspiration in preserving and growing heritage varieties of edible plants that allow us to find harmony through small community self-sufficiency.

Keely Davies

Illustrator

Keely Davies is a science illustrator with a serious passion for insects and parasites. She often ventures outdoors with the intent of self-educating and learning more about her surroundings. This fervent desire and drive to learn plays a prominent role in the development of her illustrations, as she seeks to educate others about nature and science. She often uses humor in her artwork as a communicative tool to stimulate the public’s interest in biological subjects that have sparked her own curiosity.