When heroics aren’t enough

Whales have made a spectacular recovery since being hunted to near-extinction. Vicky Stein talks to scientists who wonder if that recovery can last. Illustrations by Valeria Pellicer and Liana Vitousek.

Illustration: Valeria Pellicer

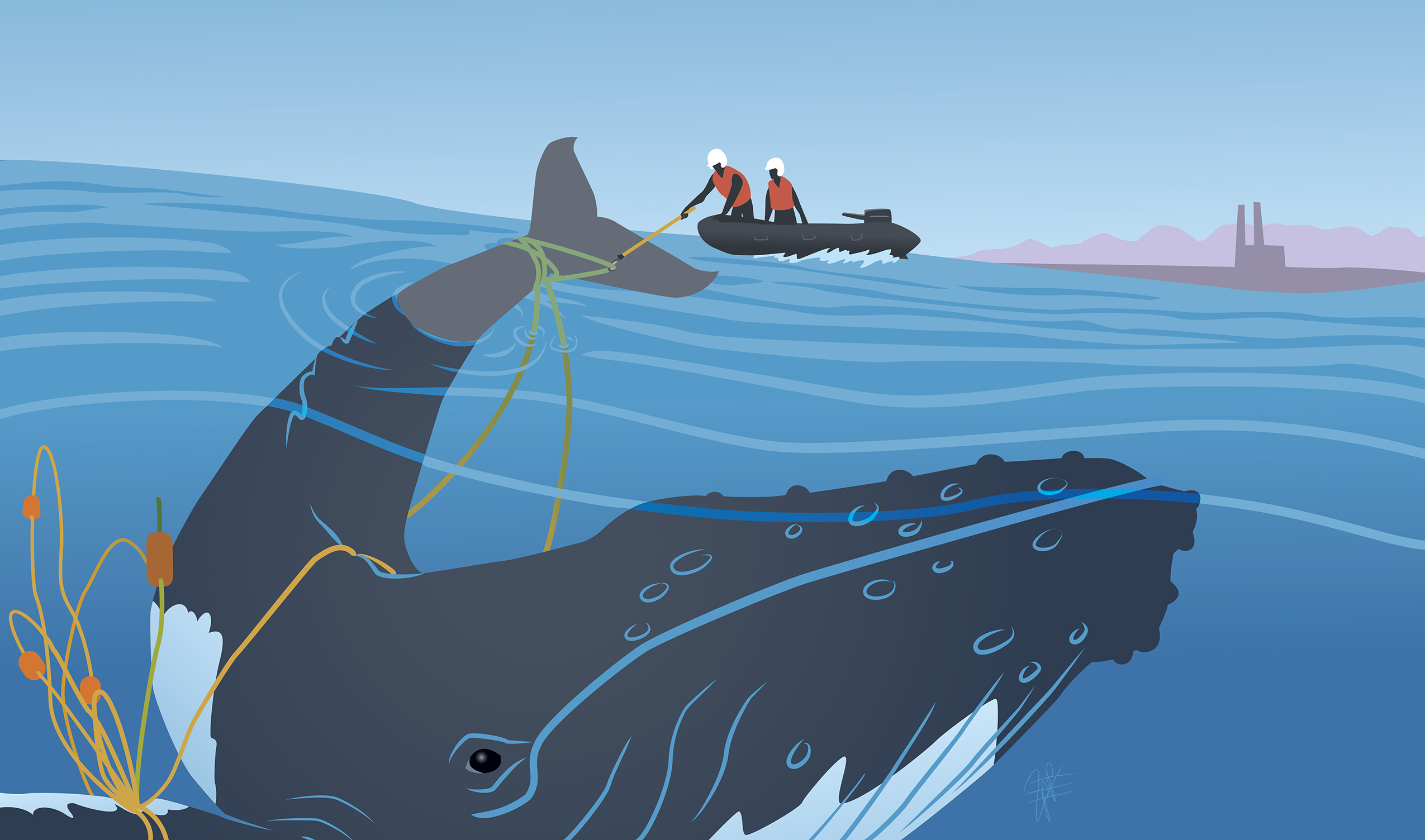

On a fall day in 2014, a team of volunteers prepared to free a young humpback whale from a cable that had ensnared the animal. Hot, rancid whale breath bathed their small inflatable boat as a 10-foot high plume of water vapor erupted from the animal’s blowholes.

From a few hundred yards away, Peggy West-Stap coordinated boats, cameras, and people. West-Stap has dedicated her days to leading the charge to free whales from deadly obstacles in California’s Monterey Bay.

Team members approached the whale wielding underwater GoPros on long carbon-fiber poles. They were trying to get a better view of the cable that was digging deep into the whale’s skin and blubber, slicing through the animal’s tissue like wire through soft cheese. The whale had been tethered to the ocean floor for three weeks, afloat near a weather buoy; the line attaching to the buoy to the ocean floor had pinned the animal in place and cut off blood supply to the animal’s tail. By the time West-Stap’s team arrived, she could see that the broad tail was dying from oxygen loss.

As trained volunteers used a specialized knife to cut the binding cable away from the whale’s skin, the blunt side of the blade sank unnervingly into the necrotic tissue. Freed of its constricting ties, the whale finally swam toward the horizon, prompting cheers first from volunteers in the inflatable boat and then those looking on from a distance. But West-Stap and the team still feared for the youngster’s fate. Would it survive without its tail? Or would the animal escape into deep water only to die and sink to the ocean floor, a casualty of human intrusion?

Peggy West-Stap is co-founder of the Whale Entanglement Team (WET), a network of central Californians who spot, study, and help to release ocean giants from human-made obstacles. She coordinates local volunteers, researchers from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), engineers, and fishermen in Monterey Bay to free whales like the juvenile humpback that her team helped to release in 2014. But as the problem of whale entanglements worsens, it’s unclear whether her volunteer force is up to the task of saving these endangered animals from increasingly dire threats.

Humpbacks and grays, the most frequently seen large whale species in Monterey Bay, weigh as much as two fully-loaded eighteen-wheelers. Blue whales, also seen off the California coast, are the most massive animals to have ever lived on the planet. They have enormous watchful eyes and mysterious, remote lifestyles; for most people on whale-watching trips in the Bay, seeing one break the surface from a quarter-mile away is enough to spur cheers and awe. Whales seem untouchable—bigger and stronger than anything else in the ocean.

But entanglements occur when whales become wrapped up in human-made ropes, cables and nets. Whales can become entangled in fishing gear, like the hundreds of feet of rope that tether crab traps to floating buoys. Some entanglements are caused by scientific equipment like underwater microphones and weather buoys. Whatever the cause, when a whale’s flipper or fluke joints snag a tough line, the line can dig deep into the whale’s skin. Some whales are pinned in place, unable to pull free from the seafloor; some whales are strong enough to drag line, traps, and other debris behind them for thousands of miles. In any case, as a line tightens around a whale’s fluke or flipper, it can slice into their skin and

For years, the number of whales entangled near Monterey Bay has been growing. Each dot represents one reported and confirmed entangled whale. Image by Vicky Stein

blubber, cutting off blood vessels or amputating limbs. Whales can die of infections and injuries or starve to death over months.

Whale entanglements have been on a rapid, alarming rise over the past few years. After decades of hovering near 10-20 reports per year, the number of whale entanglements leaped to 57 in 2015, and 2016 broke federal records with 66 entanglements reported along California’s long coastline.

Whales have made a spectacular recovery since being hunted to near-extinction during the 19th and the first half of the 20th century. After receiving federal protection in the 1970s, several species of whales are frequently seen migrating through and feeding in Monterey Bay once again. But scientists now wonder if that recovery can last. Despite the overall recovery of humpback whales, for example, certain genetically distinct groups of the animals are still on the federal endangered species list. One of those endangered populations spends its winters reproducing in Central America and its summers feeding off the coast of California. Researchers worry that if any whales from that group (or the endangered blue whale population, or the nearly extinct Western gray whale population) die due to entanglement, those populations might shrink to dangerously small numbers once again.

When whales do become entangled, volunteers with the Whale Entanglement Team mobilize to rescue them. Safety reasons and legal protections for marine mammals dictate that NOAA must oversee all whale rescue efforts. But NOAA can’t keep boats and teams out on the water day and night along California’s vast coast. That’s where West-Stap’s volunteer force comes in.

SOS-WHALE

When a fisherman, whale-watcher, or recreational boater spots an entangled whale, they call 1-877-SOS-WHALE, the NOAA whale entanglement hotline. And if that entangled whale is anywhere near central California, NOAA calls in their local team–including West-Stap.

A bubbly woman with a cheerful, Midwestern-tinged demeanor, West-Stap was born and raised in Michigan, where she lived for 41 years. But in 1996, she took a vacation to the Hawaiian islands, caught one look at a powerful humpback whale from a whale-watching boat, and fell in love. She sold her landscape and greenhouse business and started splitting her time volunteering at a whale conservation foundation in Hawaii and an ocean conservation organization in Monterey. She realized that while Hawaii had a federally-recognized, well-trained team ready to rescue entangled whales, California had nothing comparable. West-Stap set out to fill the void.

In 2009, West-Stap founded a research foundation based in Moss Landing, California, called Marine Life Studies, dedicated to researching and advocating for whales and dolphins. She raised hundreds of thousands of dollars to buy a boat and began tracking the movements and behaviors of non-endangered whales and dolphins at the heart of the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. On one of the very first days that her boat was in the water, NOAA called: a humpback whale was entangled in Monterey Bay and needed her help.

Over the next several days, West-Stap and her volunteers kept track of the animal, watching its movements and condition until volunteers with NOAA training and certification to approach whales arrived. One volunteer described the sense of exhausted relief and accomplishment she felt as the freed whale swam into the sunset.

Now, when West-Stap gets a call, she swings into action, calling in volunteers to find, observe, and photograph the whales. It’s dangerous and difficult to operate watercraft near entangled whales, because the powerful animals in distress and pain can unintentionally capsize small boats, crush their occupants, or send them into the cold ocean water. So NOAA allows fewer than five volunteers in central California to actually approach and cut the whales free. West-Stap herself isn’t certified to perform this job; instead, with her volunteers, she motors out to find and stay with an entangled animal until a certified person arrives to cut it loose.

Vicky Stein profiles a team of volunteers who scour Monterey Bay for imperiled whales. Illustration: Valeria Pellicer.

Justin Viezbicke, the NOAA Marine Mammal Stranding Coordinator for California, has led the state’s whale disentanglement efforts since 2013. Until just a few years ago, he says that between 10-20 animals became entangled in the state’s waters per year—not enough to impact the overall recovery of humpback and gray whale population recovery. But in 2016, there were 23 individual confirmed reports of entangled whales in the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary alone – the highest number of entanglements in the area since NOAA began recording data in 1986.

And while Viezbicke and others think increased awareness of the whale entanglement hotline could result in increased reports of entangled whales, many of the entanglements can’t be explained away. Scientists think that a combination of unusual currents, bad timing, and a steadily increasing whale population was to blame for the unusually high year of entanglements they saw in 2016 – a year that struck fear into the hearts of whale researchers and conservationists.

“Not only is the individual animal suffering, there is the potential that if we take too many, that can really impact the population,” says Viezbicke; by “take,” Viezbicke means “kill.”

Larger, more robust populations, like the several thousand whales that winter near Mexico, might be able to survive deaths from entanglement, ship strikes, and other threats. But smaller, more vulnerable groups like the Costa Rican/Central American humpbacks feel the impact of every loss, according to researchers. Before that disastrous season in 2016, that population was estimated at a mere 411 whales—too few to afford the loss of breeding-age animals.

Animation by Liana Vitousek

But West-Stap’s efforts to save the whales are controversial. Some researchers and activists call whale disentanglement a Band-Aid, not a solution—and an expensive Band-Aid at that. A single disentanglement attempt requires specialized equipment, such as carbon-fiber poles, high-tech buoys and cameras, and days of operations on a dedicated boat. These costs can run into the tens of thousands of dollars per rescue.

“It’s a bad way to die,” said Viezbicke. “It can be a very painful and very drawn-out process.”

West-Stap estimates that roughly 60 percent of whales that frequent Monterey Bay have entanglement scars. Some of these animals must have shaken themselves loose early enough to avoid death but late enough to have accumulated deep wounds, infections, or amputation from tight ropes and heavy equipment. These are the luckiest animals; most entangled whales probably go unnoticed, un-rescued, and end up eventually permanently scarred or dead along the enormous west coast, researchers say.

“The likelihood of seeing an entangled whale and being able to mount a response are pretty slim,” says Karin Forney, a NOAA ecologist who studies whales in Moss Landing. “Even if things line up perfectly you’re only going to be able to disentangle a fraction of the whales. It’s both not very effective and it’s dangerous.”

In 2017, for instance, an experienced and dedicated whale rescuer and fisherman named Joe Howlett died while working to disentangle a northern right whale off of the coast of New Brunswick, Canada. In the wake of the tragic accident, NOAA shut down all disentanglement operations across the continent for four days. Disentanglers are back at work, but with a sobering reminder of the danger of their missions.

But it’s hard to find an alternative to the boat-based rescues. The majority of entanglements on Monterey Bay happen in crab trap lines, and in 2015, the California Dungeness Crab Fishing Gear Working Group convened fishermen, management agencies, conservation groups and disentanglers, including West-Stap’s organization. The working group, convened to tackle the entanglement problem, has produced a new “best practices” guide for crab fishermen, which advises them to use less rope and avoid known humpback whale feeding areas. But, frustrated with the lack of concrete action or policy change, the Tucson-based non-profit Center for Biological Diversity left the working group in 2017 and filed a lawsuit against the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. The non-profit accused the fishery management agency of failing to sufficiently protect endangered humpbacks, blues, and leatherback sea turtles and hopes to put legal pressure on the agency to crack down on the crab fishery.

Forney is studying weather patterns, currents, and food webs in an attempt to predict where whales will gather, in hopes of warning fishermen not to put their crab pots in these locations. Her work might provide a better early warning for high-risk situations like the 2016 season, but variable ocean and climate conditions make forecasts like hers very difficult.

While scientists wait for such studies to yield answers, they concede that it’s distressing to watch an entangled whale struggling. Viezbicke was there in 2014 when the young humpback was freed from the weather buoy that had trapped it in Monterey Bay. He remembers, in visceral detail, the sight and sickening decay of the whale’s dying tail fluke.

“It’s a bad way to die,” said Viezbicke. “It can be a very painful and very drawn-out process.”

Video by Vicky Stein

And so West-Stap persists in her efforts to aid suffering whales. At a recent public event in Monterey, she and her team raised funds for their boat, demonstrated disentanglement techniques, and showed off some of their equipment.

“Those poles are what we use to connect telemetry buoys to a whale,” she explained to a visitor. “And then we use knives like these to actually cut the lines.” Her visitor’s eyes widened as West-Stap brandished a stainless-steel blade, blunt on one side and wickedly serrated on the other.

West-Stap is worried for the whales. She knows that her organization can’t save the creatures on their own, and doesn’t know how long it will take for fishermen and scientists to put an end to disentanglements.

But even though it’s impossible to know what becomes of the creatures she saves, West-Stap tries to draw strength from her successes, occasional and uncertain though they may be.

“It’s fun to watch a whale swim away,” West-Stap says. “It just makes your heart sing.”

© 2018 Vicky Stein / UC Santa Cruz Science Communication Program

Vicky Stein

Author

B.A. (Ecology and Evolutionary Biology) Dartmouth College

Internships: Stanford News Service, MBARI, The Monterey County Herald, UCSF Public Affairs, PBS NewsHour

Vicky Stein belongs near the Pacific Ocean, but is thrilled to be working in Arlington, Virginia for the year writing and producing science content for PBS NewsHour. Find her near local rivers and streams imagining the stench of whale breath and the sound of boat engines.

Valeria Pellicer

Illustrator

B.F.A. (Illustration) Academy of Art University, San Francisco

Internship: Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology (Claremont, CA)

Born and raised in Mexico City, but recently moved to California. My driving passions have always been art and animals. I remember my father calling me and my twin sister over as a very young child to watch nature documentaries with him. What I saw and learned about on television I then took to paper. As I grew older, art became more of a focus, but I never lost my love for drawing animals and learning about nature. I ultimately chose art over science when I attended art school, but the natural world is still my chief subject matter and source of inspiration in my art. Scientific illustration, as a field where my two passions intersect, seems an ideal fit for me, and I am beyond thrilled to have attended the science illustration program at CSUMB.

Liana Vitousek

Illustrator

B.S (Natural Resource Ecology and Minor in Plant Biology) University of Vermont

Internship: Pacific Grove Natural History Museum (Pacific Grove, CA)

Liana was raised bouncing back and forth between Hawaii and California, and developed a strong passion for the outdoors from numerous road trips across the West with her dad. She likes to spend mornings a home reading and hanging out with her cat Koa, and afternoons making the most of California sunshine.